An Interview with Stanley Whitaker: Guitarist of the American Progressive Rock Band Happy the Man

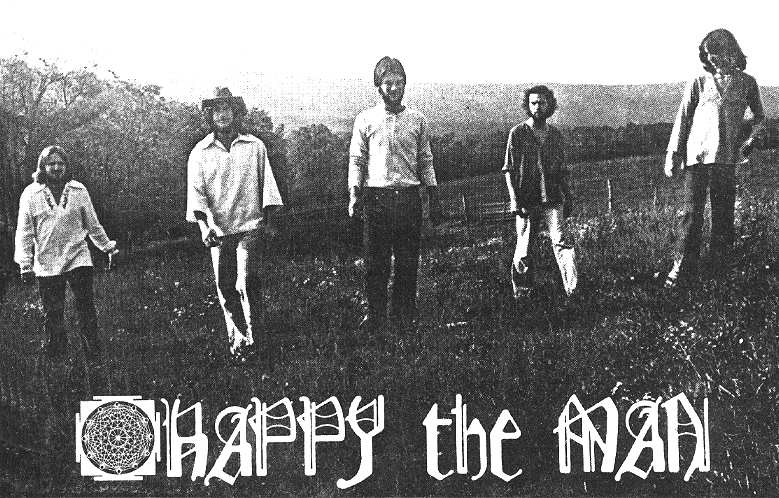

Formed in the mid-’70s, Happy the Man stands as one of prog rock’s most unique and underappreciated acts.

Formed in Harrisonburg, Virginia, by guitarist Stanley Whitaker and bassist Rick Kennell, the band’s sound was shaped by the era they emerged from, blending an eclectic mix of jazz, classical, and rock influences into something entirely their own. What set them apart in a genre often known for its bombastic tendencies was their refusal to follow typical prog rock conventions. Led by guitarist Stanley Whitaker, Happy the Man fused intricate technicality with a rare warmth, delivering songs that were complex but still inviting.

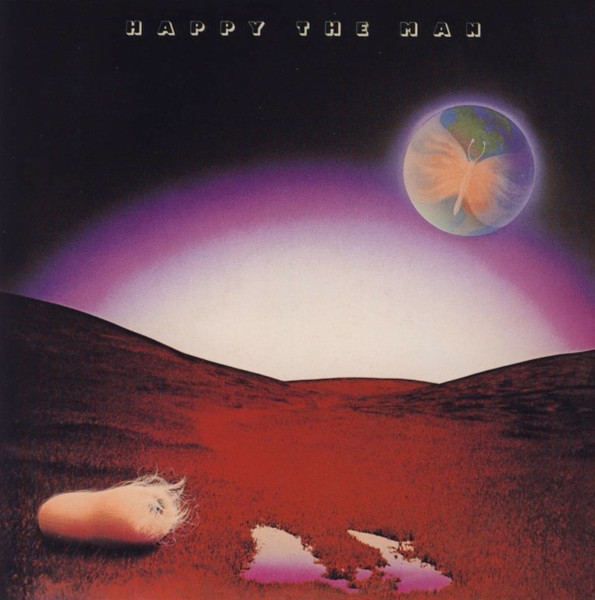

Their self-titled debut in 1977 and its follow-up, ‘Crafty Hands’ (1978), featured complex compositions, brilliant arrangements, and Whitaker’s distinctive guitar work… Though they never achieved the commercial success they deserved, their music resonated deeply with a dedicated cult following, and their legacy remains one of subtle brilliance in prog rock history, defined by a sound that never conformed to the usual norms of the genre.

“We obsessed over perfection, but we always tried to be melodic.”

Happy the Man’s formation in 1973 coincided with a time when progressive rock was flourishing globally. What was it about the musical landscape of the early ’70s that inspired you and Rick Kennell to create a band like Happy the Man? Did you feel like pioneers in the U.S. scene, given prog’s heavy European roots?

Stanley Whitaker: We did feel a bit like pioneers in the U.S. We also felt we were very unique and different from most of the popular European proggers who influenced us.

The band’s name, inspired by Goethe’s Faust and biblical references, carries philosophical weight. How did this name encapsulate your collective vision for the music and identity of the band?

My older brother Ken came up with the name, and we simply felt it was as different and original as our music was. It wasn’t as dark and brooding as a lot of other prog bands… it was “happier.”

Who were the most influential musicians for you personally, and what elements of their style did you admire or adopt?

The Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck, Free, and Humble Pie. I was always a rocker at heart, and I also loved Debussy, Ravel, and Stravinsky. Liked all of the obvious proggers but loved Gentle Giant! All-time favorite prog group… musically and personally… huge impact and influence on me.

Let’s step back to your early days. Where did you grow up, and how would you describe your upbringing?

Born in Monett, Missouri, in 1954. My father was a full colonel in the Army and was quite strict. Learned honor and discipline from him. He was horrified when I brought home the first Hendrix album! My mother was an artist, played organ, and was responsible for the artsy side of me. Learned empathy, compassion, and love from her. We moved every 2–3 years to wherever my dad was stationed, so that was both good and bad.

When did music first captivate you? Could you talk about some of the key influences that initially shaped your musical interests?

My mother, with classical music and big band initially. But my aunt Fanny Mae was a brilliant pianist and exposed me to classical music and my love for Debussy. She performed for a few presidents at the White House for dinner parties and events. It wasn’t until The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show that everything shifted for me. Wanted the screaming girls to be quiet so I could hear the music! From ‘Rubber Soul’ on, they are still my all-time favorite “progressive” band! Who progressed more from album to album than The Beatles? Nobody… and then there was Jimi… mind blown… knew what I wanted to be when I grew up…

Were you involved in other bands or projects before forming Happy the Man?

My first band was called The Imposters when I was 12 years old. We won a talent contest, and they made a big deal about the guitarist being only 12 years old! I was in two bands in high school in Frankfurt, Germany, that were both pretty hip—Ulysses and Shady Grove. We played some Jethro Tull, some Yes, some King Crimson, and some originals. We were playing stuff nobody was playing… fond memories…

What kind of music did Zelda play back in Fort Wayne, Indiana? The band had drummer Mike Beck and singer/flautist Cliff Fortney, who both agreed to move to Virginia…

Zelda was a very cool band that Rick Kennell formed, and you’ll have to ask him more about that venture.

How did the idea for Happy the Man come about, and when did the band officially form?

In the summer of ’72, Shady Grove had the opportunity to tour all of the Army bases in Germany for the Davis Agency, which flew all military personnel and their families back and forth between the States and Europe. Our parents went back to the U.S., and we stayed for the entire summer with my older brother Ken, who acted as a sort of chaperone—but he would also sing some songs and paint during our shows. He was a brilliant artist.

Rick had just joined the Army and was at one of our shows. He and Ken talked about prog music, and then we jammed with him—he knew ‘The Knife’ by Genesis, which totally blew us away. He played it flawlessly, so I told him I was going back to the States to form a prog band and asked if he’d be interested. He was on leave, and he and Mike Beck drove out to Virginia for a week. We played together in our dorm room at Madison College in Harrisonburg, VA (now James Madison University). We cleared out the entire room, set up our gear, and had a lot of fun… school wasn’t too happy with us. Soon after, Rick got out of the Army, and he, Mike, and Cliff moved into our first of many band houses.

Your early repertoire included covers from Genesis, King Crimson, and Van der Graaf Generator. What lessons did you learn from interpreting their work, and how did this influence your original compositions?

We just needed more material, so we did a handful of songs from the bands we liked. I recall playing piano on ‘Man-Erg’ by Van der Graaf, which was challenging because I didn’t play piano. But we were already developing our own thing…

“We seemed to have a way of making odd time signatures feel like 4/4.”

Happy the Man’s music is often described as intensely intricate yet emotionally resonant. How do you balance technical complexity with accessibility?

Great question… we rehearsed 6–8 hours every day, sometimes more. We obsessed over perfection, but we always tried to be melodic. We approached arrangements more like an orchestra—there wasn’t much improv in Happy the Man! We were blessed to have three very different writers, but we managed to keep it cohesive. We seemed to have a way of making odd time signatures feel like 4/4. The new HTM is much more accessible, methinks…

The interplay between Kit Watkins and Frank Wyatt’s keyboards became a defining feature of the band’s sound. Can you share insights into how this dynamic developed, and how you adapted your guitar playing to complement their unique approach?

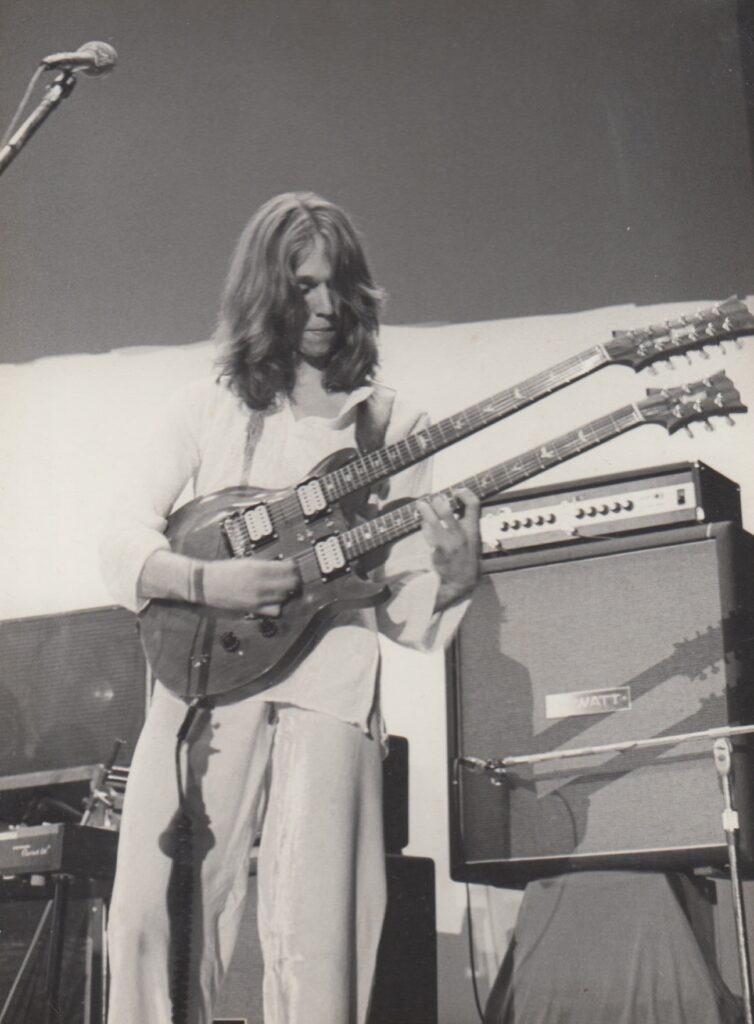

That ties into the orchestral approach. They worked so brilliantly together with their keyboard parts, and I would try to simply complement what they were doing and not get in the way. I considered myself as adding texture to a lot of the music. When there was a spot for a solo, I preferred to work it out note for note so that it became part of the arrangement—I was happy to perform it the same way every time. No improv. I would develop the solo by improvising, but once I was happy with it, it was set in stone.

Progressive rock often challenges traditional song structures. How did the band approach the composition process for pieces like ‘Starborne’ or ‘New York Dream’s Suite’? Were these collaborative efforts, or did individual members bring in near-complete works?

Most pieces were fully completed works on the instruments they were written on, but we allowed each band member to experiment and create their own parts. We were very good communicators with each other—no egos. Everyone stayed humble and respectful. We truly were a family, loved each other, and always did what was best for the song.

How did you get signed to record your debut album?

We played often at the Cellar Door in Washington, D.C., and had developed a nice following, with radio support from WGTB. We signed with Cellar Door management, and then some A&R folks started coming to see us. Stu Fine from Arista really liked us and brought us up to New York, where we auditioned for Clive Davis. He signed us on the spot—mostly because his head of A&R, Rick Chertoff, loved us. Clive appreciated us but didn’t love us like Rick did, but he signed us anyway because he greatly respected Rick.

What was it like working with Ken Scott on your debut album? Did his experience with artists like David Bowie and Mahavishnu Orchestra shape your recording process in ways you hadn’t anticipated?

He had just done ‘Birds of Fire,’ which is why he was our first choice for producing our record. He was brilliant to work with and had so many great ideas during the process. The only song he really changed was ‘Carousel,’ which originally had many different parts, but he loved the ending so much that he wanted just that part to repeat over and over again, with us adding the spice on top of it… brilliant. It was an unforgettable experience for us—magical—and we truly managed to capture “lightning in a bottle.”

How much time did you spend recording the album, and what was the experience like in the studio?

We spent a lot of time—six to eight weeks, I think. And I guess I answered the experience portion in the above answer.

Could you share your thoughts on the songwriting process? What inspired the tracks on the album?

They were the tracks we had performed and perfected over six years. Ken had input into the songs, which thankfully aligned with our thoughts. The only song we actually wrote together was ‘Wind Up’—Frank wrote the lyrics, and Kit and I wrote the music.

Peter Gabriel’s brief collaboration with the band is a fascinating footnote in your history. How did that encounter influence you?

Well, he was my favorite singer, so that was a wonderful experience! We spent six to seven hours together. He wanted us exclusively, but we had worked six years to get a deal and had Arista wanting to sign us, so we followed our hearts.

‘Crafty Hands’ is such a stunning follow-up. With tracks like ‘Steaming Pipes,’ what do you feel the band achieved artistically on that record that you hadn’t accomplished with the debut?

Well, it was a ballsier record overall. Ron Riddle on drums made a big difference, and we had very little rehearsal time before recording, so it had a bit more of a spontaneous feel. I had a bit more control over my guitar parts on ‘Crafty’—didn’t have to double every single guitar part.

What was the main concept behind your first two records?

On the first album, everything was so tight and scripted, and we were so well-rehearsed. The second was much looser. Our concept was simply to create music that was adventurous and unique.

When the band parted ways with Arista after ‘Crafty Hands,’ how did that affect morale? Was there ever a temptation to pursue a more commercially viable sound, or did you feel compelled to remain true to your original path?

It sucked, but it didn’t change our musical direction. No temptation at all… we were on a mission.

Despite limited mainstream success, Happy the Man has maintained a devoted following and is considered a cult favorite. Why do you think your music resonates so deeply with fans even decades later?

I suppose it’s because it was so unique. We didn’t really sound like anyone else, and folks either loved us or hated us—there wasn’t much in between. The music had some soulful magic in it, which gives it longevity, I guess.

Your 1979 demos, later released as ‘3rd – Better Late…,’ contained a treasure trove of unreleased material. Looking back, do you think that album would have changed the band’s trajectory if it had been released during its initial creation?

No, I don’t think so… we were an acquired taste no matter when it came out.

The ‘Death’s Crown’ suite is an ambitious and lesser-known part of your catalog. How do you view its importance within Happy the Man’s artistic legacy, and are there plans to revisit or expand on it in any way?

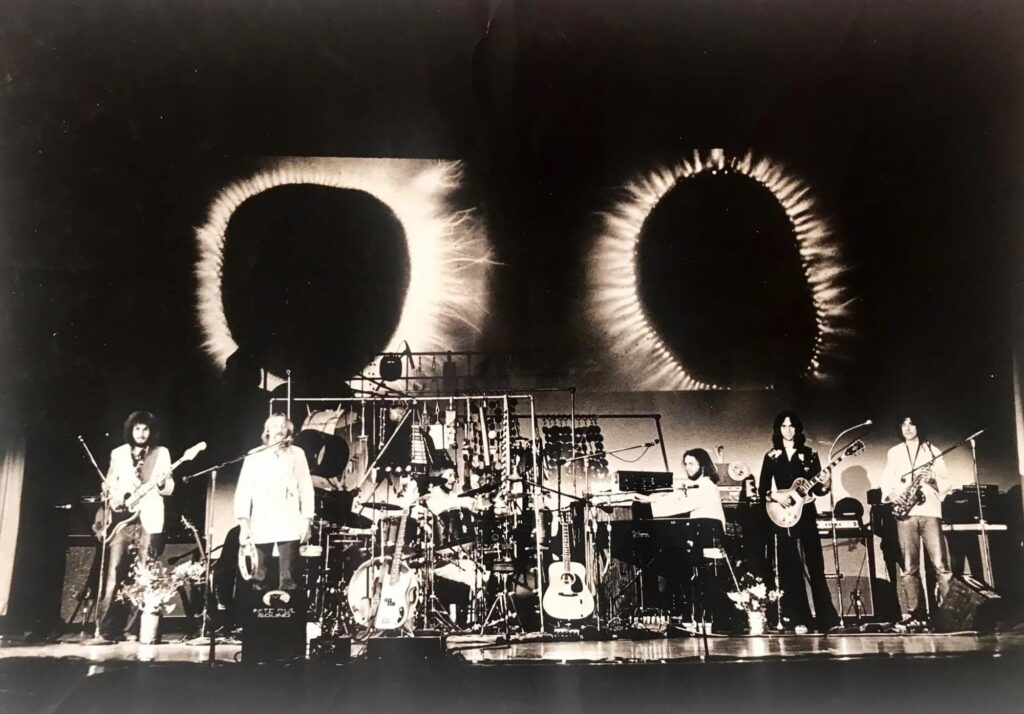

No plans to revisit. It was quite the production—with actors, dancers, a light show—and we were in the orchestra pit. We only performed it a few times. ‘Open Book’ came out of it for the ‘Crafty Hands’ album.

What can you say about Vission?

Very cool, rocking band with Rick and me and an unbelievable singer named Rocky Ruckman… longgg story…

After decades apart, what inspired you to reform the band in 2000? How did the addition of new members, such as drummer Joe Bergamini and keyboardist David Rosenthal, influence the dynamic and sound on ‘The Muse Awakens’?

We had an opportunity to headline NearFest in 2000, so I moved back to the East Coast and we got it together. Ron did some shows with us and then went on the road with Blue Öyster Cult. Dave was the only guy we knew who could fill Kit’s shoes, and he knew Joe. They each added their own thing and did quite admirably.

What challenges did you face in rekindling the chemistry and creative spark after such a long hiatus?

It was different but the same… still had similar chemistry but different flavors… it was fun.

Your guitar work has always been central to Happy the Man’s sound. Over the years, how has your approach to the instrument evolved, both technically and philosophically?

Wow, good question! I was always more textural in my approach with HTM… I was part of the orchestra. The rare guitar solo became part of the arrangement—every note counted. I think I’ve become more melodic and more tasteful in my old age… melody and fire.

Tell us about some of the most memorable gigs.

Those would be most of the shows we did at Wilson Auditorium at Madison College. They were transformative shows… clowns jumping out of the balcony… any outrageous things we could think of… very wild light shows.

What would be the craziest one?

Probably opening for Hot Tuna at the Commack Long Island Arena… 10,000 people chanting “Hot Fucking Tuna” while we opened our set with ‘Stumpy’ and had bottles and quarters thrown at us… quite the crazy experience… we barely made it off the stage!

Looking back at your career, are there moments or decisions that you view as pivotal in shaping the band’s journey—for better or worse?

Yeah, we should’ve gone with Peter.

Do you see your compositions as reflections of specific personal experiences, or are they more like abstract expressions of collective imagination?

A little of both… I always had imagery in my head to go along with my songs back then. Now I’m more of a protest singer in my old age, but I love singing and writing lyrics much more than in the old days… I was the reluctant singer back then.

Are you active in any other projects currently? Like, for instance, Oblivion Sun, Six Elements, Stan and LeeAnne, or Frank Wyatt and Friends?

None of the above… only brand-new Happy the Man is keeping me busy. Different from the old HTM, but still hints of it… more rocking and more vocals. ‘Only Love’ and ‘Lock’em Up’ are the latest two I’ve written, but the next ones are instrumental… just going with the flow and having fun.

As you continue to create and perform, what does the future hold for Happy the Man? Are there any new projects, recordings, or reissues on the horizon that fans can anticipate?

Both Arista albums were remastered at Air London and are being released in May on Iconoclassic Records. We have discovered some old audio and video gems that will likely be coming out. No live plans… but you never know.

Thank you for taking the time to speak with us. Is there anything else you’d like to share with our readers?

Just love and hugs to any and all fans of our music… you are very special. Please share our new songs and keep the faith, brothers and sisters!

Klemen Breznikar

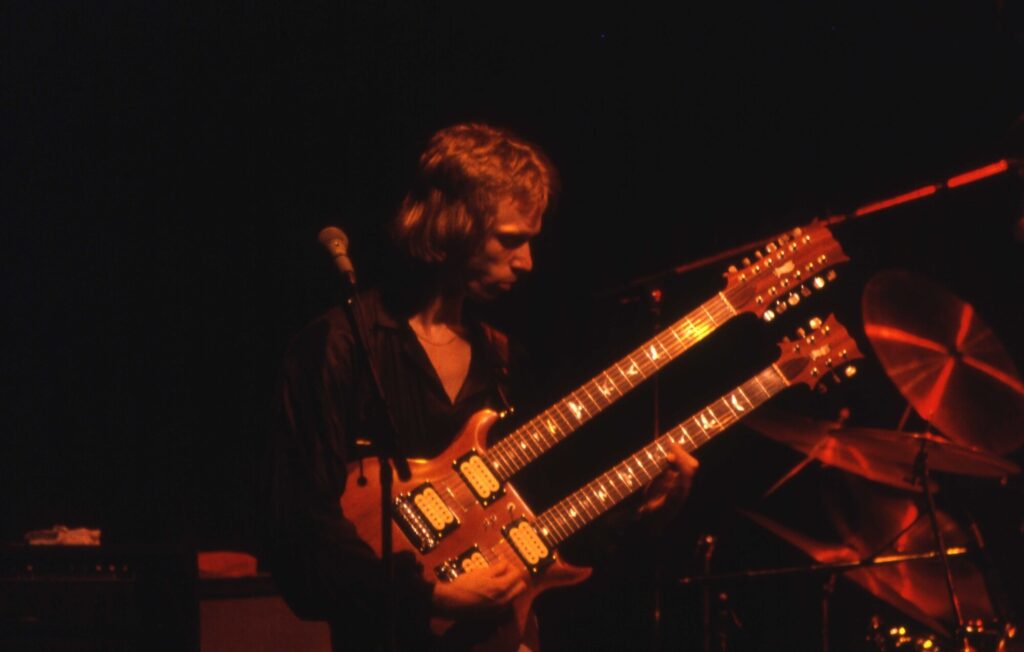

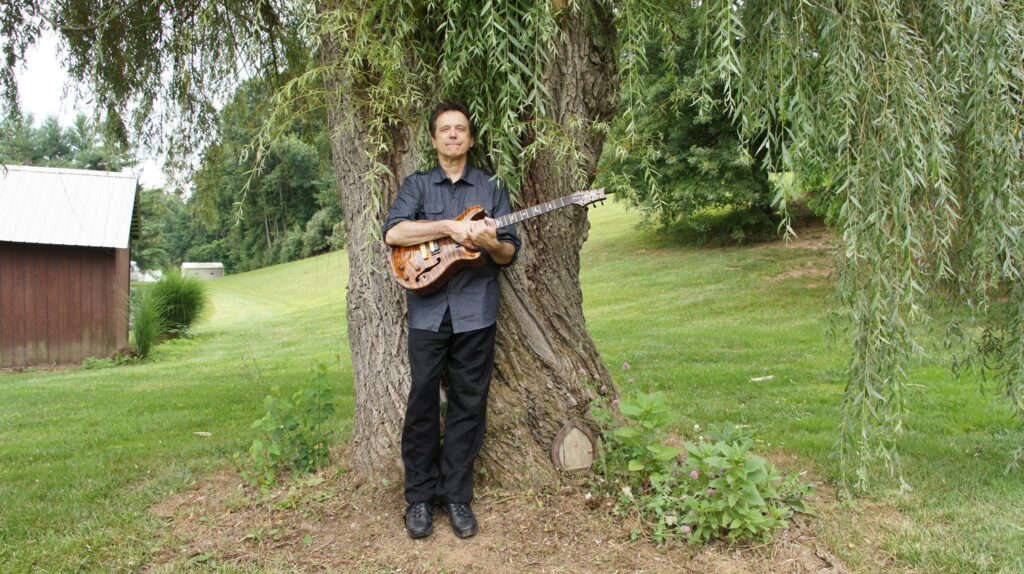

Headline photo: Happy the Man performing live | Photo by Thomas Born

All photos are copyrighted by their respective owners and are used for informational purposes only. There is a fantastic and insightful Facebook group dedicated to Happy the Man, where most of these photos were sourced.