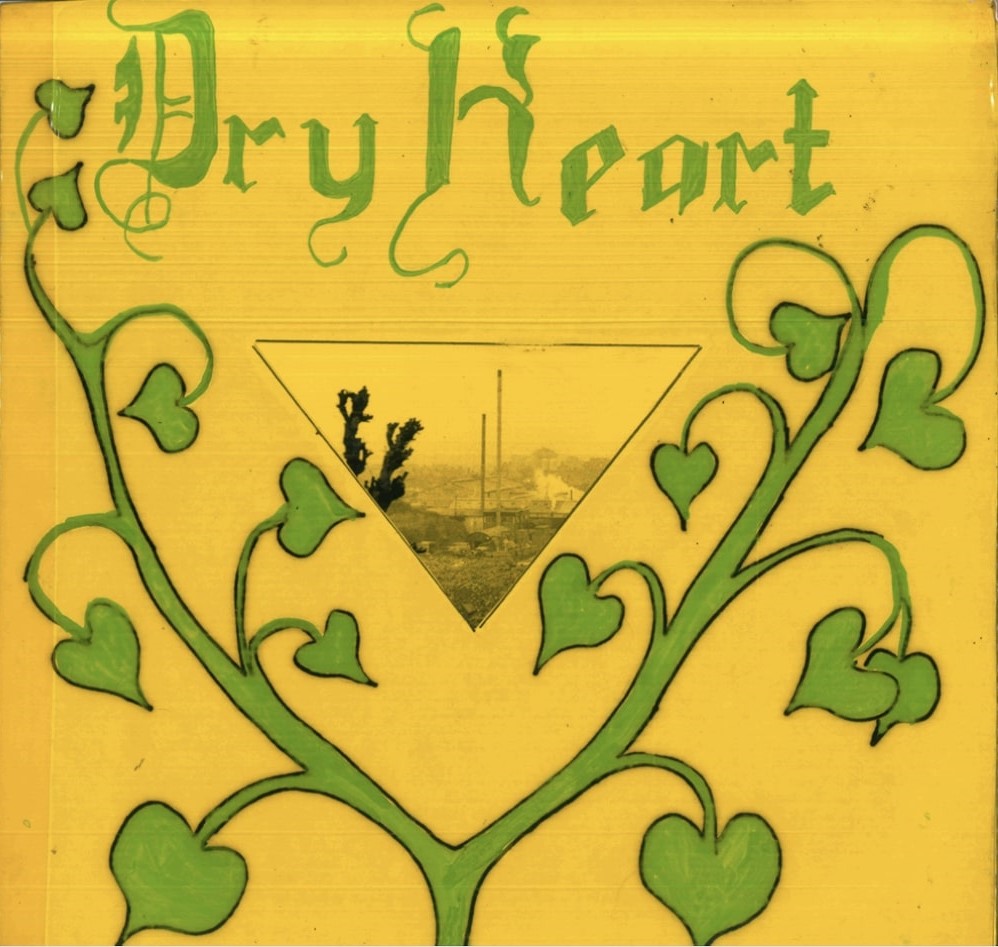

Lost Psych-Folk Acetate ‘Dry Heart’ Resurfaces After 50 Years

The first-ever reissue of Dry Heart’s impossibly rare 1970 acetate is finally here, and it’s one for the true psych-folk heads.

Originally pressed in just 10 copies on Deroy, this Guerssen reissue brings back the charm of a record that’s as elusive as it is special. A raw, homemade affair, it captures the essence of a band clearly influenced by the likes of Incredible String Band, Fairport Convention, and John Fahey. The male/female vocals, guitars, mandolin, percussion, and flute create a sound that feels as intimate as it does expansive, blending folk and a kind of quiet, melancholic psychedelia.

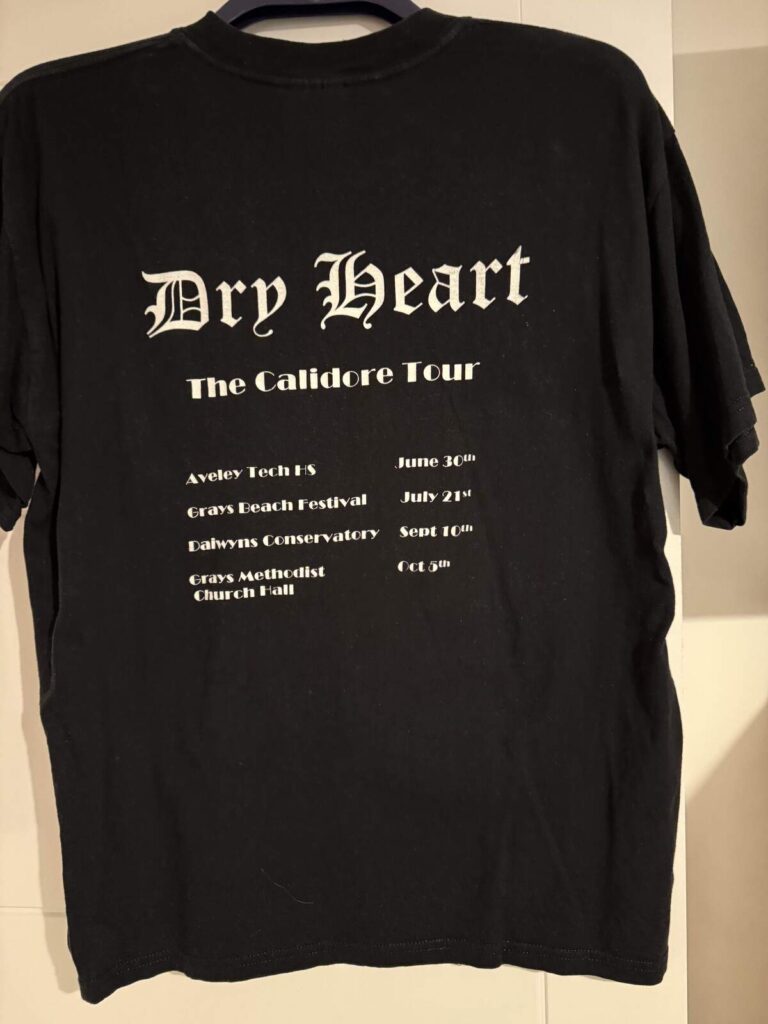

The standout here is the 16-minute ‘Calidore,’ a lo-fi, melancholic progressive folk epic that stands the test of time. It’s a track that begs to be filed next to the likes of Shide & Acorn, the kind of folk-flavored weirdness that feels like it belongs to another era. Six original tracks in total, each with its own peculiar beauty, replete with the kind of spirit that only a band recording in their living room can capture. With remastered sound and the original artwork, this is a trip back in time worth taking.

“a kind of postcard to ourselves, sent from early 1970”

Let’s start from the beginning. What was growing up like for you? Were there any moments or experiences in your early years that pushed you toward music?

Martin Palmer: I think all four of us were interested in music from an early age. As a young child in the 1950s, skiffle and rock’n’roll were the latest thing, and like lots of kids our age, we saw people like Lonnie Donegan on TV and thought, “that’s it.” For me specifically, I was 14 when I saw my first live professional gig—it was Bob Dylan and the Hawks at the Royal Albert Hall. Needless to say, it was a pretty explosive experience and inspired me to start trying to play the guitar a year or so later.

What was the local music scene like where you grew up? Were there many folk bands around, or did you feel like you were operating on the fringes of something different?

Our local music scene was very active. We lived in South Essex, which was home to many rock bands who had gone, or were about to go, on to greater things—Procol Harum, Humble Pie, Dr. Feelgood, and Kursaal Flyers, to name just a few. There were (and still are) some very well-established folk clubs where most of the top performers could be seen on a regular basis. There were also lots of semi-pro bands, mostly contributing to the electric blues boom. However, as we were all very young (17 or 18), still at school, and our repertoire consisted entirely of original acoustic material, most potential venues were out of reach for us. Consequently, the few gigs we did play were mainly self-organized and fairly small-scale.

Do you remember the first record that truly stopped you in your tracks? Something that shifted the way you thought about music?

There were lots of records that had that effect, but the first one I was able to buy (6/8d for a 45 rpm single in 1965) was ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues.’ It seemed to compress all the different things I’d liked up to that point into 2 minutes and 17 seconds—Chuck Berry meets the Beat Poets, sung by a suitably rocked-up Bob.

Before Dry Heart, did you play in any other bands or musical projects? If so, what kind of music did you play, and how different was it from what you ended up doing with Dry Heart?

For about a year before Dry Heart, Les and I played guitar together informally on weekends. We had very similar tastes in music, ranging from Bob Dylan and the Byrds to the Witchseason acts like Fairport Convention and the Incredible String Band. Also, when it came to playing guitar, we had complementary styles and techniques—Les was a natural lead player and more “rocky,” whereas I was more of an accompanist with traditional folk leanings, although there was a very large area of overlap. However, neither of us really sang at that time, so most of what we played was purely instrumental and strongly influenced by people like John Fahey and his Takoma label mates. That was how we started composing our own material, with titles like ‘The Dance of the Sacrificial Onion’ and ‘Chestfield-Swalecliffe Halt,’ prior to trying to write actual songs.

How did the members of Dry Heart come together? Was it a gradual formation, or was there a specific moment when you realized this was the band?

Les, Pete, and I were all at school together, so when Les and I decided to try writing songs, we looked for somebody who could sing them. Pete was in the school choir, so he seemed a likely candidate. We then thought that a female voice would complement Pete’s very nicely, although as we didn’t really know many girls at that time (our school was boys-only), that was slightly problematic. However, another of our school friends mentioned that his sister could sing, and Anne was gratefully recruited to the lineup. She, along with four friends, had created the “Aveley and Grays High School Folk Group,” had performed at lots of local events, and fortunately for us, liked the songs we had. At that point, it felt as though we had something that worked.

Was there a particular concept or vision behind Dry Heart? Did you set out to create a certain kind of sound, or was it more organic?

To a large extent, Dry Heart’s sound was always going to be primarily acoustic guitar-based, as that was what we had. This wasn’t because we didn’t like electric guitars—far from it—it was simply that we didn’t have any. Hence, Les’s occasional use of his acoustic guitar fitted with a pick-up and using a record player as an amp to get a “kind of” electric sound. (If we had known then what we now know about the subtleties of proper electric guitar tone, I suspect we probably wouldn’t have done it…) But we also had lots of other influences—people like Love and The Misunderstood, where electric and acoustic guitars were blended in a way that we saw as a source of inspiration and aspiration.

The original acetate pressing of your album is almost mythical now. Can you walk us through the recording process? Where was it recorded, and what were the conditions like?

The recording process was actually very straightforward, in the sense that — as is clear from the recording — we weren’t really too aware of what was required technically. We simply gathered in Les’s living room and performed the songs in the order they are on the record, with our friend Geoff recording them on a fairly typical-for-the-time basic reel-to-reel mono tape recorder. The result has since been described by David Wells as “not so much lo-fi as no-fi,” which is 100% accurate…

Was it meant as a demo, or was there an intention to distribute it more widely?

I don’t think we thought of the acetate as a demo — it was mainly meant to be a record of what we had been doing, and which was more permanent and convenient than a reel of tape (we didn’t really consider the obvious alternative — a cassette — because we didn’t know anybody that had a cassette recorder…). We were very keen to do as much as we could with Dry Heart, but there was also a reluctant recognition that, as we would all eventually be going our separate ways and leaving school (and home) to become students in different parts of the UK, we would have to make the most of it while we were able. So, what we were really trying to do was to create a Dry Heart memento — a kind of postcard to ourselves, sent from early 1970…

Where was the acetate pressed, and how did that process unfold? Given that many acetates never make it past that stage, what was the original plan for these recordings?

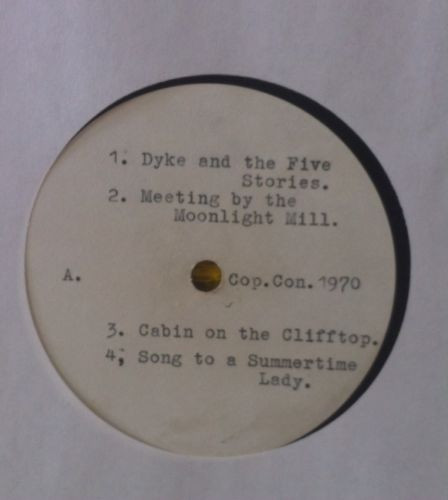

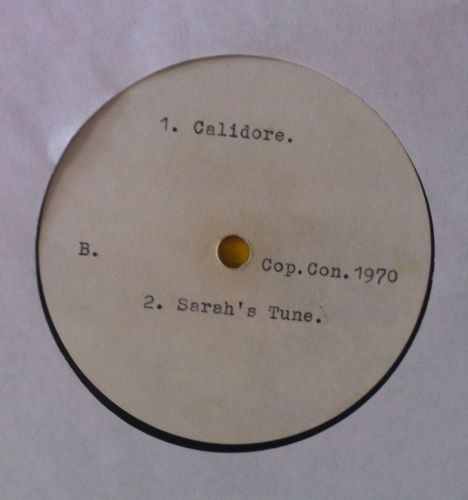

The acetate was pressed by Deroy Sound Services, who were based in Carnforth in Lancashire. Again, getting an acetate made was a very simple process — you simply sent a tape to the company and a few weeks later the requisite number of acetates would be sent back (if you ordered a larger number, then vinyl versions were also available). We now know that lots of bands made use of the company at the time. However, none of us can remember exactly how many acetates we had made, but it was certainly no more than ten.

“We were about as “underground” as it was possible to be”

Did Dry Heart ever receive any local airplay or press coverage back then?

Dry Heart didn’t get any local airplay or press coverage at the time — and I think we would have been very surprised if we had. We were about as “underground” as it was possible to be, and reasonably happy to be so!

What were the gigs like? Do any particular performances stand out as especially memorable, for better or worse?

Gigs, as previously mentioned, were comparatively few and far between. But they were generally very enjoyable, as it felt good to be able to play the songs to a live audience. And, in retrospect — and having played a few hundred gigs with other bands in the years since — I think our limited experience of playing in front of people meant that we weren’t fully aware of all the things that might go wrong…

Did you share the stage with any bands that left a lasting impression on you? Any musicians that you felt a kindred spirit with?

We didn’t quite manage it, although we came close at one point. We were scheduled to appear at a local festival, but for various reasons we weren’t able to play. The headliners that day were UFO, who were still in the comparatively early stages of their career. Their brand of hard rock was just about as different from Dry Heart as it could be, but it was very interesting to be up close and personal to a professional band doing that kind of material.

What was the most chaotic or unexpected moment at a Dry Heart concert? Any stories that, looking back, feel almost too wild to be true?

Probably the most chaotic element of our gigs was our lack of equipment. In contrast to today — when most buskers can be heard from across a busy street using compact, powerful, and reliable amplification — playing acoustic music sufficiently loudly for an audience to enjoy then was a rather more hit-and-miss affair. As we had no PA or amplifiers of our own, we were entirely dependent on what a venue could provide — or else be content with a small-ish audience. We once played an event alongside some very loud electric bands in a school hall. The PA wasn’t able to pick up our acoustic instruments, so we had to stop playing in the hall and give an impromptu all-acoustic performance outside on the school playing field.

When and why did Dry Heart disband? Was it a natural ending, or was there a specific event that led to it?

As mentioned, we soon reached a point where we all went off to different parts of the country after we left school, with Les and I departing first. However, we did all keep in touch and kept on producing new material. We shared it via snail mail and then got back together during the holidays to practise and occasionally perform. However, when Pete and Anne also went off to study elsewhere the following year, the logistics became too difficult to overcome and it all came to a natural end during 1971.

Are there any unreleased recordings still around, maybe even from a side project?

We ended up with about 15 or so more songs, and we had plans to make a second recording called Execution, based on a short story written by our friend Dave (which is now featured in the Guerssen Dry Heart package). There are some surviving tapes, but their quality is very poor.

Before the reissue, how often did you think about the record? Did you ever imagine people would rediscover it after all these years?

We often thought about the Dry Heart record over the years, but never really thought it would find a wider audience. In fact, for about forty-five years, it didn’t. Then, about ten years ago, two things happened independently of each other. Firstly, somebody sold one of the acetates online for an eyebrow-raisingly large amount of money, and secondly, Cherry Red Records invited us to contribute a track to their ‘Dust on the Nettles’ box set. We joked that, if Marty McFly had driven his DeLorean past Les’s house when we were recording and told us that people would be listening to our stuff in the 21st century, we’d have told him to go Back to the Future 2…

How did the Guerssen reissue come about? Did you have any reservations about revisiting the music after so many years?

I’m not sure how that happened—Alex Carretero contacted me a couple of years ago via Facebook to see if we were interested in working with Guerssen to produce a limited edition of the whole Dry Heart album. Alex obviously knows a huge amount about this kind of music, and so presumably was aware of us through his sources.

The record is clearly very much of its time, and it’s interesting that ‘psych folk’, or whatever you want to call it, very much fell out of fashion in the early ‘70s, but a new audience has grown up for it in the last ten years or so…

Can you share any insights about the tracks on the album? Any particular stories or inspirations behind them that haven’t been discussed before?

A1 ‘Dyke and the Five Stories’: This was the first song we wrote, and the intro is a nod in the direction of John Fahey.

A2 ‘Meeting by the Moonlight Mill’: Again, some Fahey-esque stuff, this time a cautionary tale in open D tuning.

A3 ‘Cabin on the Clifftop’: The arrangement is influenced by the Fairports (although they probably wouldn’t recognize it…), and the story is meant to be a kind of ‘All Along the Watchtower’ in a parallel universe…

A4 ‘Song to a Summertime Lady’: The third alliterative title in a row, although we didn’t notice at the time. And another aspiring Fairport-type song, although you probably wouldn’t know without being told…

B1 ‘Calidore’: See below.

B2 ‘Sarah’s Tune’: See below.

‘Calidore’ is a standout—16 minutes of haunting folk beauty. Do you recall what inspired that track? Was it always meant to be such an epic piece?

We were, self-evidently, big fans of the Incredible String Band at that time, and this was our attempt to emulate their multipart pieces like ‘Maya’. Les had written a fairly comprehensive lyric about Calidore and his quest, and it seemed to lend itself to that kind of musical setting.

The final track, ‘Sarah’s Tune,’ feels like a left turn, almost country-like. What’s the story behind that song?

This was meant to be a singalong bit of light relief after the previous track, in a kind of Basement Tapes way. We liked the fact that the Flying Burrito Brothers had a song called ‘Christine’s Tune’, so we thought we’d do something similar. In retrospect, we should probably have called it ‘Anne’s Tune’ (this was before John Denver claimed similar territory), although that would have been a bit confusing as it’s the song that features her least. So, rather more obliquely, it’s called ‘Sarah’s Tune’ in honour of Bob Dylan’s wife at the time (although it turns out she is called Sara…). The lead vocal sounds different from the other tracks because it’s me rather than Pete or Anne.

Looking back, how do you feel about Dry Heart’s music today? Does it still resonate with you, or does it feel like a distant relic of another time?

It’s a bit of both, I think. Obviously, it’s a reflection of the era in which it was made, and of the age and experience of the people who made it; it’s difficult to think back now to what it was like to be 17 at the start of the 1970s, but there are flashes of it on this record…

I also think parts of it are still quite intriguing and sometimes wonder what it might have sounded like if it had been recorded in a proper studio. But, on balance, its homemade nature is probably better suited to its content than a Dolby Atmos remix might have been…

And finally, what occupies your life these days? Are you still making music in any form, or have you ventured into different creative paths?

Les and I got back together musically in 2002 and formed a band called the A13 Allstars (the A13 is a road in South Essex that links the towns where we lived in the Dry Heart era). We played mainly Americana material—Dylan/Byrds/Grateful Dead/Burritos, etc.—and happily performed over two hundred gigs up until a couple of years ago.

Sadly, neither Les nor Pete lived to see Guerssen’s release of ‘Dry Heart,’ but we know how much they would have enjoyed it.

Klemen Breznikar

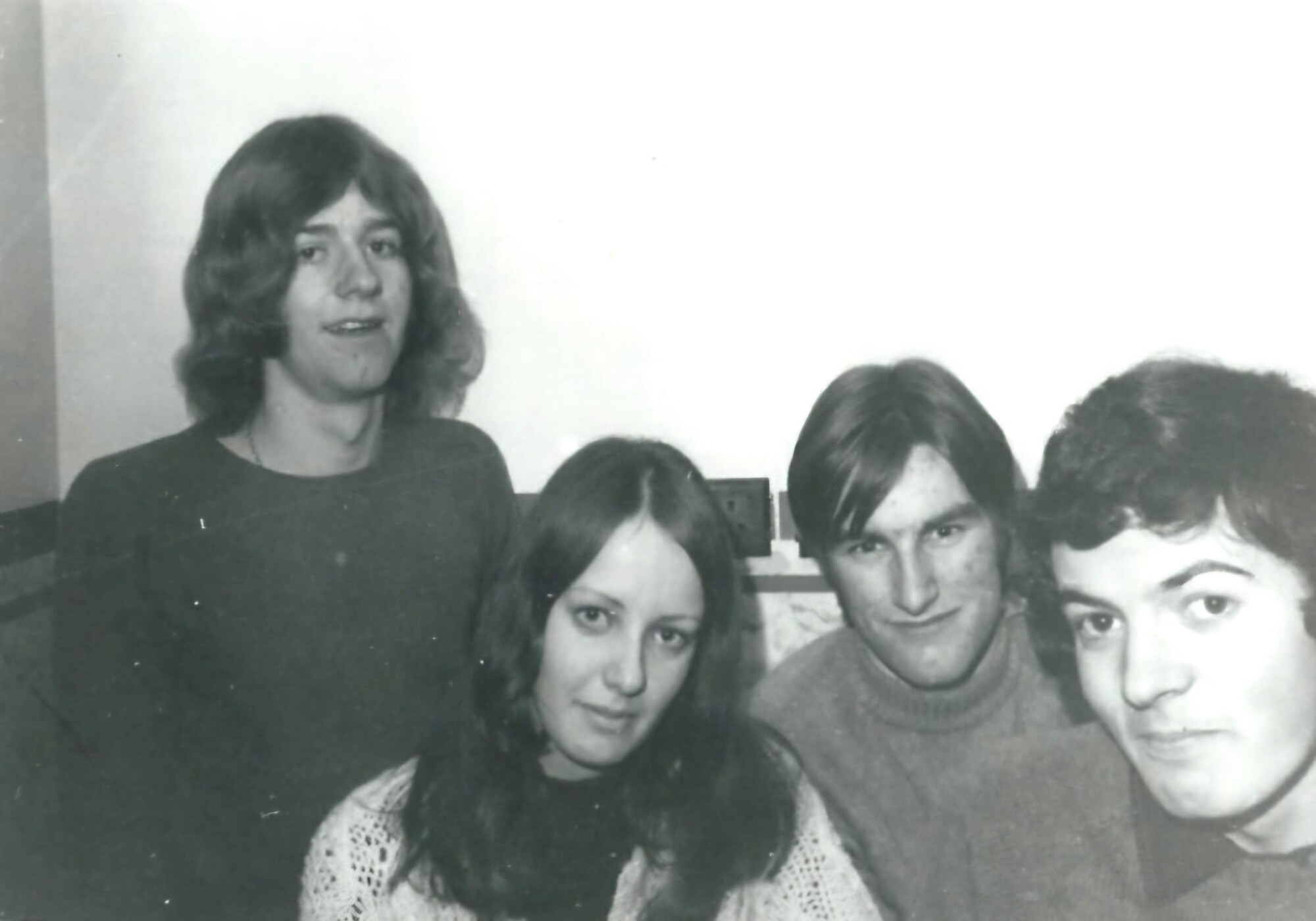

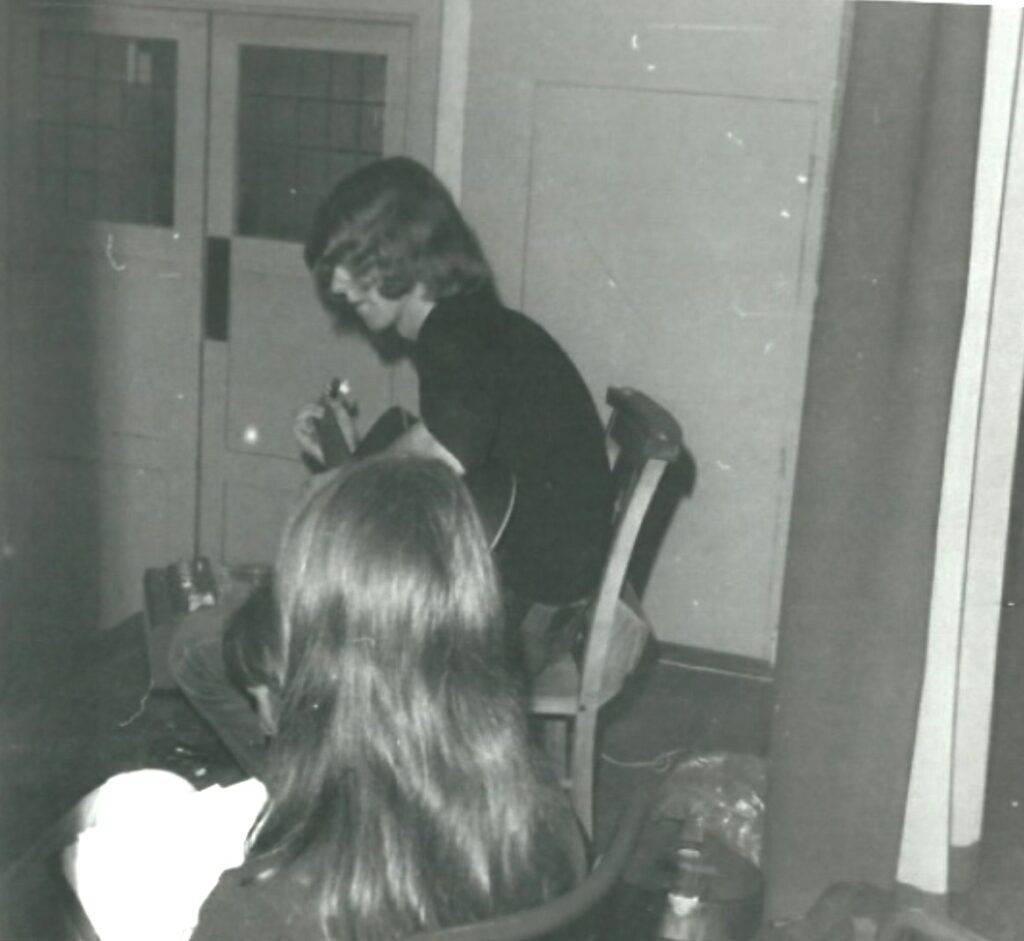

Headline photo: Les Greenacre (guitar, mandolin, cover artwork), Anne Rance (lead vocals), Peter Llewelyn (lead vocals, percussion and bamboo flute), Martin Palmer (guitar, vocals)

Guerssen Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube