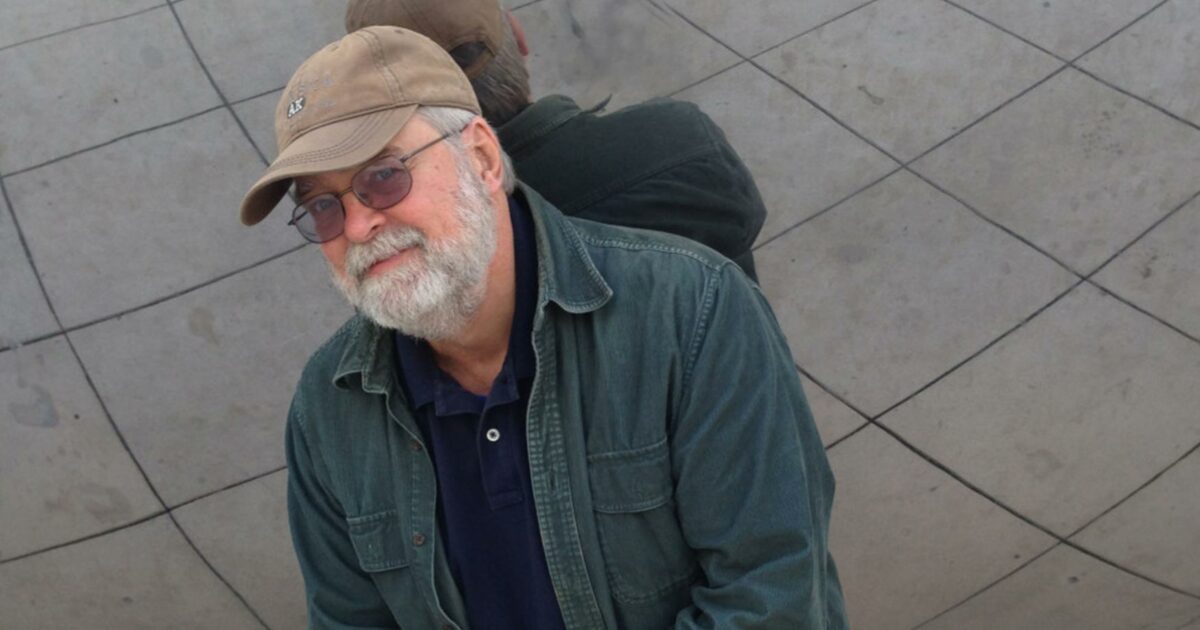

Roberto Musci | Interview | “My idea of music is the union between different types of tradition”

Roberto Musci is an adventurous musician whose work breaks down borders and blends a rich mix of global sounds into something uniquely his own.

Born in Milan in 1956, he’s been on a lifelong journey, traveling the world since 1974, recording African, Indian, Arabic, and Oriental music, and collecting ethnic instruments. His debut album, ‘The Loa of Music,’ is a fascinating blend of field recordings, electronics, and global influences that instantly set him apart.

Musci’s collaborations read like a who’s who of the avant-garde scene, having worked with legends like Chris Cutler, Keith Tippett, and the Third Ear Band. His 1987 album ‘Water Messages’ on ‘Desert Sand,’ a collaboration with Giovanni Venosta, even earned a Grammy nomination. Over the years, he’s experimented with his audio-visual installations, live performances, and other projects, all while embracing both tradition and innovation. His music is a bridge between cultures and time, a constant exploration of travel, mysticism, and the universal language of sound. ‘Goodbye Monsters’ is his latest release available on Soave Records.

“Sound has been defined as the essence of the known world”

Your musical journey began in Milan with studies in guitar and electronic instruments. What initially drew you to music, and how did your upbringing in Milan shape your artistic vision?

Roberto Musci: Music has captivated me since I was little. My father played the guitar in his free time, and there was always music to listen to at home. My mother really liked art, especially painting, and I still remember the reproductions of paintings by Gauguin, Cézanne, and Monet hanging on the walls of my old house.

I still remember Gauguin’s paintings with images of distant countries… maybe that’s where my desire to travel began.

Milan was fundamental. Between the late ’60s and early ’70s, Milan was an extraordinary crossroads of art, music, and culture. I still remember the first rock concerts I was lucky enough to attend (Led Zeppelin, Genesis, Van der Graaf, Black Sabbath, Jethro Tull, Gentle Giant).

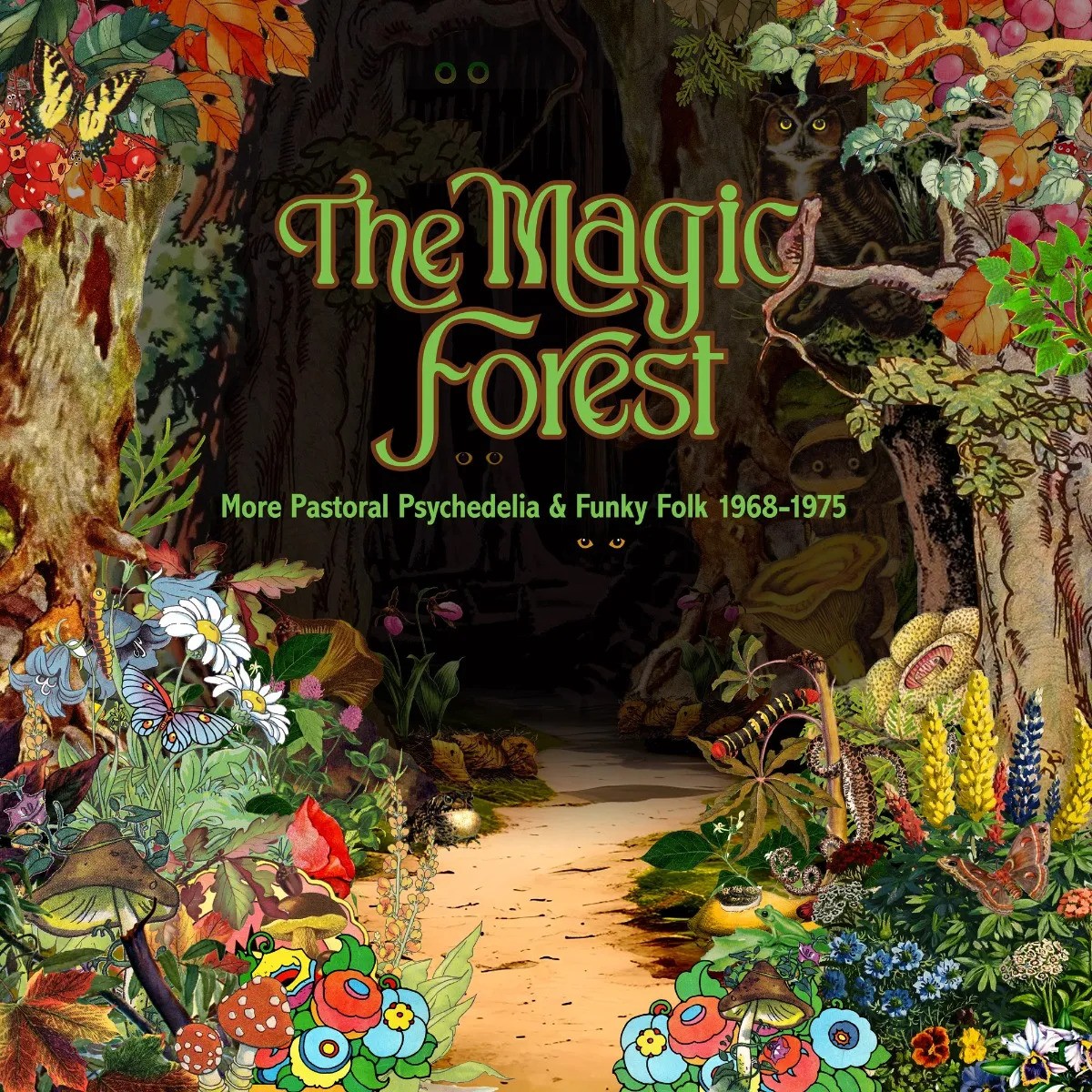

The discovery of extraordinary albums such as ‘Bitches Brew’ by Miles Davis, minimal music (Reich, Glass, Riley), Quintessence (a group that combined Indian music with rock), and the Third Ear Band (a little-known group that greatly influenced my music). The discovery of jazz contaminations (Coltrane’s Indian modal music, Archie Shepp’s African influences, Tony Scott’s Japanese “chamber” music).

From 1974 to 1985, you traveled extensively, immersing yourself in the music of Africa, India, and the Near and Far East. Can you share a moment or experience from those travels that profoundly influenced your work?

Certainly, the encounter with Indian music and, in general, with the culture and daily life in India.

The encounter with an absolute, very ancient music played with extraordinary musical instruments. A music linked to the Raga (melodic line) that arouses Rasa (emotions and sensations).

Nāda (sound) is a combination of breath and energy.

Since the most ancient times in the sacred Indian texts (the Vedas), sound has been defined as the essence of the known world. Etymologically, “Na” means breath, and “da” means energy.

I spent a lot of time in Indian and Tibetan temples listening to religious music. I was emotionally struck by the gamelan orchestras of Java and the chants for the adhan of the muezzins, heard around the Middle East.

Field recordings have been an integral part of your music. What challenges or surprises did you encounter while capturing these sounds, and how did they inform your approach to composition?

As I have often said, my music is a travel story without any compositional ambition. They are my sensations and memories of experiences lived around the world, the sounds that surrounded me (songs, sounds, noises of water, wind, breathing, voices). I tried to unite the different musical cultures with my Western culture to tell the daily life of my travels.

“I prefer to listen to the music of the places”

‘The Loa of Music’ is a remarkable album. How did your experiences and philosophies converge to create something so distinctive?

As I told you, these are travel stories made in Africa and the Middle and Far East, using sounds to recreate sensations, smells, and flavours… Everyday life, wandering through temples and forests. There are those who take photographs, make videos, or draw their travels. I prefer to listen to the music of the places.

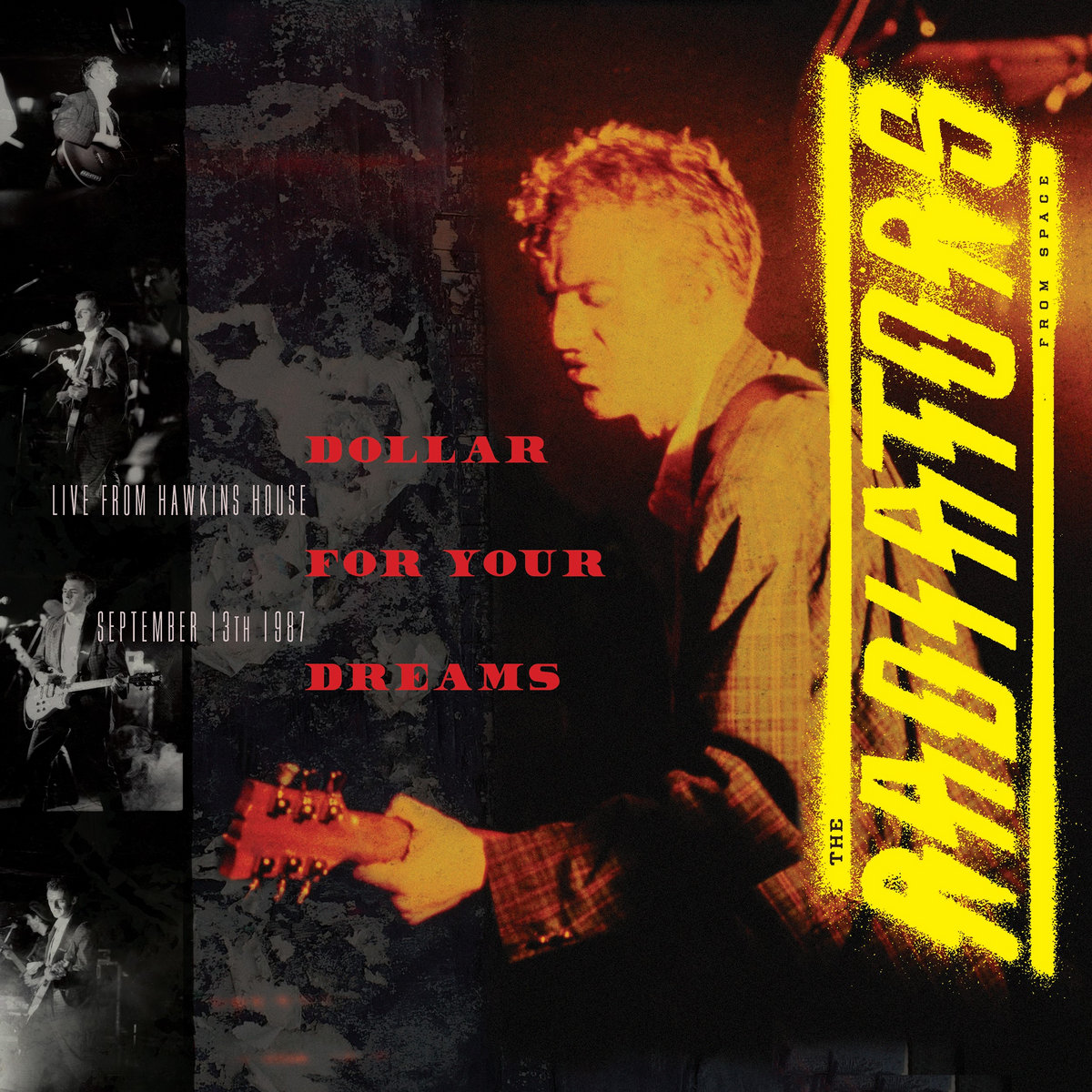

In ‘Water Messages on Desert Sand,’ your collaboration with Giovanni Venosta earned a Grammy nomination in the UK. What made that partnership so fruitful, and how did it shape your evolution as an artist?

I have been playing with Giovanni Venosta for more than 10 years. He is also a traveler, and we found ourselves on “sound journeys” to tell. We found the right narrative and musical balance between rhythms and sensations. Giovanni is much more “rhythmic,” and I am much more “ethnic.” We integrated our experiences and our musical preferences. We also share an interest in concrete music (the noises in music of the French composer Pierre Schaeffer). We often used noises recorded around the world to obtain rhythmic bases on which to compose the music.

Broadcasting ethnic and experimental music on Rai and Radio Popolare must have been an exciting time. How did curating and sharing music through those platforms influence your creative process?

I have always tried to make non-European music known, and radio broadcasts have stimulated me to delve into the musicological part and not just the philosophical or emotional one. Music is one; it must not have distinctions between East or West, or between the North and the South of the world.

“My idea of music is the union between different types of tradition”

Your work often explores the concept that “music is one,” transcending borders. How do you approach creating music that bridges such diverse cultural landscapes?

Creation is made from the memory of travel sensations that listening to music creates and my reworking of musical traditions in my personal memory.

I have always loved contaminations in music and in all the arts.

My idea of music is the union between different types of tradition. In my songs, I have combined a guitar with a Pygmy song or a Korean oboe with a Javanese gamelan. I have used avant-garde Western music together with the primitive music of the aborigines of Oceania.

Mysticism, travel, and the human experience seem central to you…

Surely, my music is born from the journey, from the sensations that the places give you, from the people you meet, from the smells and flavors that surround you.

Art does not respect borders; it transcends ethnic groups, ignores religions, and blends cultures to create surprising masterpieces.

‘Goodbye Monsters’ reflects a wide range of themes, from quantum mechanics to Sufism. What was the initial spark for this album, and how did you approach weaving such complex ideas into music?

I have created musical NFTs (digital works that combine music and images using digital platforms and cryptocurrencies) dealing with topics such as the creation of new DNA derived from alterations to our DNA (Xenobiology), biological creations from the union of silicon and carbon (Silicon Carbon-based life), and the deepening of the theory of chaos (Strange attractor).

They are not Cyberpunk inventions but real experiments that are currently being conducted in laboratories around the world.

I am trying to use A.I. in music and, in general, in the arts, in a creative way. We often talk about colonizing new worlds or parallel quantum realities… but the center of everything is us, with our desires, our feelings, and our religious faith or our atheism.

What would a Hindu or Muslim colony on Mars be like? If you believe in quantum mechanics, what will parallel universes and their religion, their music, and their art be like? The same as ours? Different, and how? Will there be a parallel universe where we will all be Muslims, Taoists, or Hindus? What music will we listen to?

Tracks like ‘Derviches on Mars’ and ‘The Principle of Things’ are conceptually rich. How do you translate abstract or philosophical ideas into sound?

I do nothing but expand the music that surrounds us into other possible variants, leaving my imagination free to unite science and philosophy, mathematics and music. I am very curious about new scientific discoveries and their possible use.

‘Memories of a Piano Player’ is a tribute to Keith Tippett, with whom you had a personal connection. Could you share more about your relationship with him and how this tribute came to life?

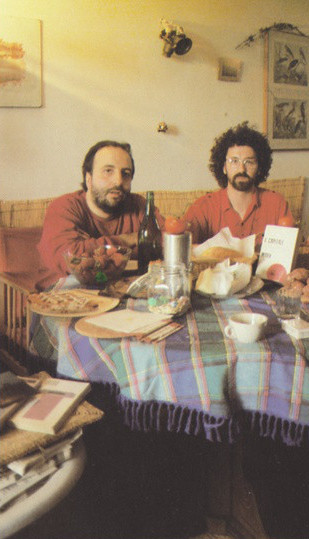

We played together live and recorded a CD of our concert (‘Music for Labyrinths’ with guitarist Claudio Gabbiani).

We spent some time together playing, talking about music, eating great Italian food, and drinking good wine.

I think Keith Tippett was not only a great musician but also an extraordinary person. It was an honor for me to play with him. I grew up on King Crimson, and playing with their pianist was extraordinary for me.

‘A.I. In Confusion’ explores artificial intelligence. What are your thoughts on the role of A.I. in music?

As always, the problem with technology is not that it exists, but how it is used. Often, music made with A.I. is standardized, always the same because it is created by algorithms (extremely complex) but still always the same.

The real A.I. should be one with which you interface and exchange sensations, music, and preferences, and that changes according to its learning and knowledge—something that interacts with you for a constant exchange.

I enjoy confusing the A.I. algorithms by asking, “I would like a piece of Indian music played in Istanbul while I walk in the equatorial forest in the Middle Ages with jazz influences”… and the most unlikely but, at times, extraordinary hybrids are born.

You’ve collaborated with an impressive roster of artists, from Chris Cutler to Keith Tippett and the Third Ear Band. Any stories you would like to share with us about it?

As for Chris Cutler, our meeting was quite bizarre. In 1982, I wrote, recorded, and printed my first vinyl record in 500 copies, ‘The Loa of Music,’ for the label I founded, Raw Material. At the end of all the work, I found myself with 10 cases of 50 records at home. And now? What do I do with them? What should I do? I sent copies of the record to various labels to ask for possible distribution.

Cutler’s record company (Recommended Records) replied, asking me for 500 copies for worldwide distribution. In this way, I met Cutler and Recommended, a label with which I recorded various LPs and CDs. I played with him and the violinist Jon Rose in some live concerts (the recordings gave birth to the CD Steelwater Light, published by Recommended), and with him and Giovanni Venosta in the live soundtrack of the film Vampyr by Carl Dreyer (the recording was taken from the homonymous CD for Recommended).

For the Third Ear Band, it was a tribute to the group that influenced me the most musically and emotionally, one that deepened my knowledge of extra-European music and culture and the fusion between different cultures.

A memory of Tippett, sadly passed away in 2020, is his advice for music: “Make sure that music is not another way to make money.”

How has your label Raw Material evolved since its inception in 1983? Do you see its role shifting further in the digital age, particularly with the integration of platforms for interactive and multimedia art?

The Raw Material project is definitely a work in progress.

It started with vinyl and continued with digital, live concerts, and the interaction between music and images, up to NFTs and A.I…. and let’s see what will happen.

With innovations like the “Extended Guitar” and your work in live audio-visual installations, how do you see the relationship between music and technology evolving?

I believe it will be an increasingly close relationship, not only due to the invention of musical instruments, musical synthesis, or extremely advanced computers and A.I. The problem, as I said, is not the technology, but how it is used.

What are you currently listening to? Would love to hear about some of your latest favorite records…

Musically speaking, I am omnivorous. I listen to everything, from pop to avant-garde music, and quoting the great and immense Miles Davis: “There is no genre better than another: music is only beautiful or ugly. Music is a question of style.”

Indian classical music is definitely my favorite.

Thank you for the space you dedicate to me in your magazine. The world is not doing so well at the moment… let’s hope that there is still time and desire to listen and make music and art. You always have to be curious to discover new musical gems, buried around the world.

To be a Rock Star, you don’t have to be a great musician, you just need to have an audience that has no historical memory.

Klemen Breznikar

Roberto Musci Website / Instagram

Soave Records Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / Bandcamp