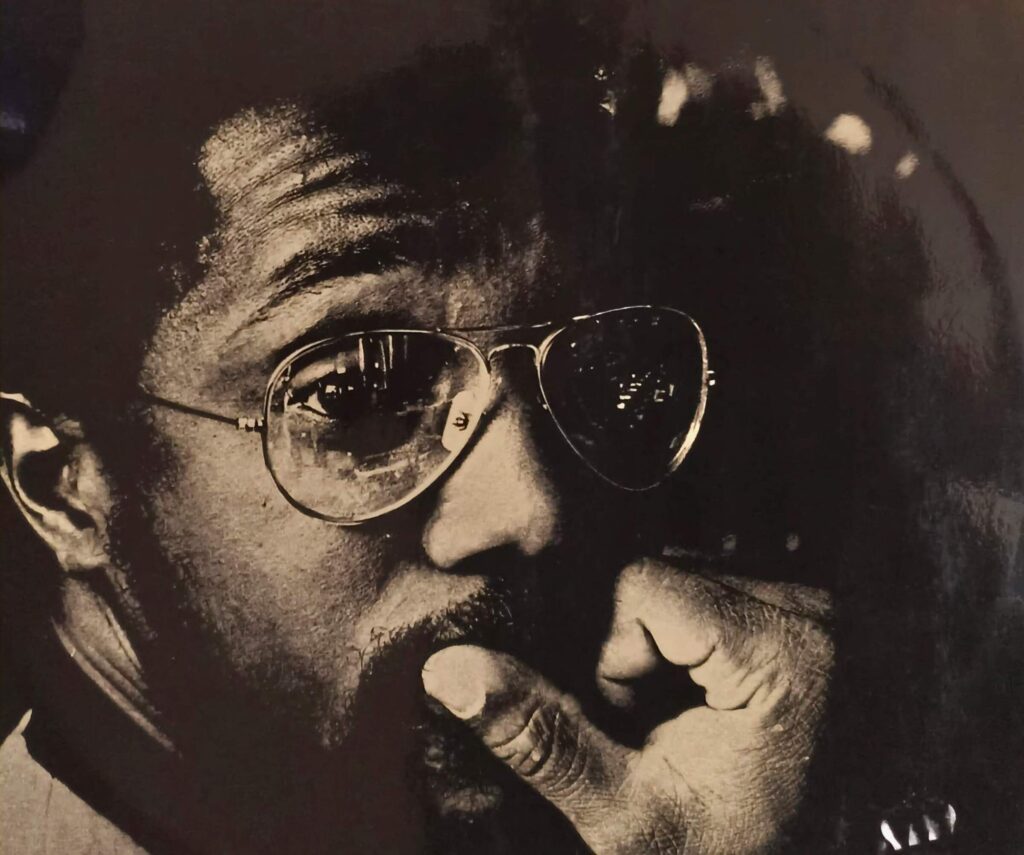

Spectrum of Sound | An Interview with Billy Cobham

Billy Cobham, an eminent rhythmic architect and fusion vanguard, has indelibly reshaped the percussive landscape of modern jazz with a visionary approach that transcends conventional boundaries.

Not only did he collaborate with jazz giants such as Miles Davis, but he also ventured into entirely new sonic territories with projects like the Mahavishnu Orchestra and his landmark album ‘Spectrum.’ As a formidable force behind the seismic energy of the Mahavishnu Orchestra, Cobham’s drumming is a masterful synthesis of explosive intensity and near-mathematical precision, while retaining an effortless spontaneity that remains truly astonishing. His 1973 solo debut, ‘Spectrum,’ shattered established paradigms by fusing thunderous power with intricately layered polyrhythmic structures, setting a benchmark that resonates with generations of musicians. Leland Sklar, who played bass on four of its tracks, noted, “Spectrum is such a benchmark for so many people. There was a sort of fire in it. It was new ground and it wasn’t very analytical. It was more flying by the seat of your pants. That’s where great accidents happen…” Every stroke of his drumsticks creates a dynamic interplay that is as intellectually engaging as it is viscerally compelling.

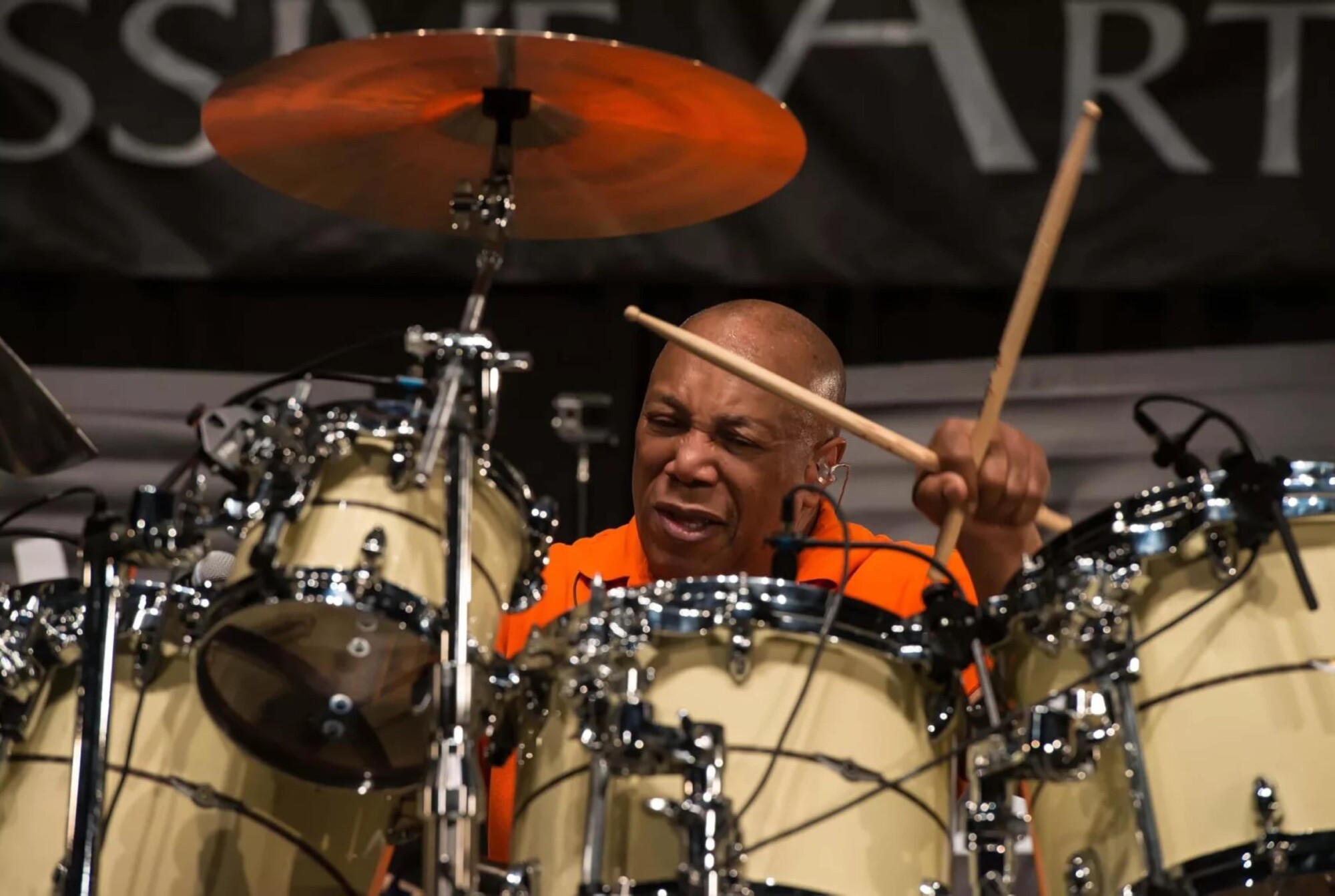

In the early stages of his career, Cobham’s work was defined by a relentless barrage of rhythmic experimentation and technical bravado. Over the ensuing decades, his artistry has evolved into a more contemplative and refined narrative—a journey from boundless rhythmic explosions to an elegant economy of expression. Today, his performances embody deliberate restraint; each note carries profound weight, and the measured silences between beats reveal a deep, reflective understanding of musical storytelling. At the 2025 Cheltenham Jazz Festival, audiences can anticipate an immersive set that not only reinterprets the classic elements of fusion but also introduces pioneering new compositions. Cobham’s transformative approach elevates drumming into an art form that speaks with the cadence and depth of poetry. His drumming: a language spoken in lightning-fast fills and grooves that defied time. Still innovating, still inspiring. A true percussive titan.

“I feel that I’ve been blessed with the gifts of observation and analysis”

In recent years, you’ve continued exploring new sounds and collaborations. What excites you most about the music you’re making right now?

Billy Cobham: “Excitement” is not the word, but at the moment, I can’t find a proper alternative… What I feel is a sense of accomplishment—that I am able to transfer what I feel internally and have it reflected in the notes I develop into a sonic platform to share.

Looking at the evolution from Spectrum to your latest projects, how has your approach to composition and rhythm evolved over the years?

I feel that I’ve been blessed with the gifts of observation and analysis. When I made the commitment to honing my compositional skills, I had a reason. Early in my career, I noticed a general lack of group interaction between musicians, whether in a jam session or in groups seeking to find a deeper, more lasting platform. They tended to play for themselves first, reflecting a competitive attitude. By choosing to study musical composition, I have sought to find a way to present, through the notes, what I hear my colleagues play—not just the frequencies, but certain aspects of musical sound bites that life presents in its various forms.

Are there any modern influences shaping your playing today?

I am influenced by all that I experience in life: what is said, what is sung, what is played, what I see, and how I interpret the information. It keeps me optimistically reaching out for more.

With Spectrum, you stepped out as a bandleader and created one of the most influential jazz-rock albums ever. What was your mindset going into that album, and did you know at the time that it would have such a lasting impact?

I chose to write material that would best represent me as a musician open to supporting others in the Latin, pop, and jazz—or jazz fusion—platforms. In other words, I created Spectrum with the idea of offering the album as a musical calling card to whomever was willing to listen—to it and to me. It was about what I could bring to the musical production table as a producer and supportive performer. I had no idea that the record would be as successful as it has been to date.

“The older I get, the fewer notes I play”

Your drumming has always had a dynamic blend of power and finesse. Has your approach to technique and endurance changed as you’ve matured as an artist?

My style of playing has changed as it has reflected me and how I have lived my life to date. Strange, but the older I get, the fewer notes I play—yet the more complex my compositions appear to be.

Over the past decade, you’ve worked extensively on educational initiatives. How do you approach passing on your knowledge to the next generation, and what do you think young drummers today struggle with most?

When I am approached by a student of the arts with a question related to what we do, I immediately seek to provide an answer with a physical solution if possible. For example: How would I play a six-stroke roll over a five-beat bar? In my mind, I have already played the example and then try to present it in real time to satisfy the query. The next level is to write it out and accompany the pattern by playing it at a tempo that we can all digest.

Jazz fusion has gone through several waves since the ’70s. How do you see your influence in the current jazz-fusion landscape?

I don’t know… I guess fluid.

Your work with Mahavishnu Orchestra was groundbreaking, fusing jazz with rock aggression. Looking back, do you think there are any musical frontiers left unexplored in fusion?

I don’t know… I wouldn’t be surprised if there are, though. Standing by…

You’ve played with legends like Miles Davis and John McLaughlin—musicians who never looked back creatively. Do you ever revisit old material with a new mindset, or are you always moving forward?

I always look back on what I have created with the idea of infusing the present into the past.

You had a strong foundation in marching bands and music education from a young age. How did that structured discipline influence the way you approached improvisation and fusion later on?

When I finally committed to performing through a jazz-based platform, I found that the first shocking point in my transition from the academic playing of marching band music was realizing that I had to round off my approach to playing rhythmic patterns in jazz. Jazz and commercial music allowed me to play with more flow and flexibility. So now, I had two roads to travel through my performance career.

The High School of Music and Art had an incredible roster of talent. Who were some of your most inspiring peers from that time?

Eddie Gomez, Larry Willis, George Cables, Fred Lipsius (original Blood, Sweat & Tears member), Janis Ian, Richard Tee.

You recorded on an incredible number of albums in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Did you have a favorite session where everything just clicked?

The Miles Davis ‘Jack Johnson’ recording.

Working for Creed Taylor at CTI Records, you were in the studio with some of the best. What was the most challenging or memorable recording session from that era?

One session that stood out for me was the Milt Jackson ‘Sunflower’ session, where I experienced Milt’s mode of performance—playing in the old duple rhythmic structure as opposed to the more fluid and rounded triplet application used by many musicians then. Our rhythm section for the date was Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Airto Moreira (I think), and me. Check out who all worked together within that sandbox.

You played on some outtakes for ‘Bitches Brew,’ and Miles wanted you to join his band. What made you hesitate?

I wasn’t ready to take on the responsibility. Bad timing for me. I was still in search mode internally.

Your sense of time and polyrhythmic phrasing remains unparalleled. What’s your perspective on groove versus technicality in drumming?

I believe that in order to groove or play in the pocket, one has to be able to stay in control of what one receives as input from one’s colleagues while making a musical contribution that sustains the groove and represents the band. This is a highly technical and emotional challenge—a very high level of multitasking for the player to achieve.

Has your sense of groove changed over time?

I believe it has changed for the better, as I find that I am very comfortable performing with or without a click track. This trait took years to develop.

You’re known for your explosive fills and incredible dynamic range. Is there a piece of music or solo where you feel you captured your absolute best drumming?

‘A Funky Kind of Thing.’

You’ll be performing at Cheltenham Jazz Festival in 2025. What can audiences expect from your set?

They will hear and experience the music of my mind.

Will you be revisiting classic material, or will there be surprises?

There will be new arrangements of old compositions and new music reflecting who I am today.

Jazz festivals have a unique energy compared to club shows. How does the festival setting influence the way you approach a performance?

At festivals, I tend to select music that I believe will be easily accessible to a large audience. People tend to want to tap their feet, bob their heads, and enjoy a musical platform that provides these elements and more. They also love to experience concepts and ideas that offer something different from what they have witnessed before. The changes don’t have to be large, but it’s a plus if they can leave feeling they’ve considered something new by the end of the day.

Cheltenham has hosted some of jazz’s greatest innovators. Do you see jazz festivals as an important space for pushing the genre forward?

Yes!

If you could have one more jam session with any musician, living or dead, who would it be and why?

John Coltrane and Jimmy Garrison.

Your music has inspired generations of drummers. What advice would you give to young musicians?

Have patience with your development—it will take the rest of your life. Your best teacher is the mistakes you make and how you solve those problems.

Klemen Breznikar

Billy Cobham Website / Facebook / Instagram / X

Billy Cobham | Jazz Legend | Interview

It’s good to see another legend featured here. Good questions Klemen, keep them coming. Although a little clipped in his replies one can see Cobham’s depth and intellect.