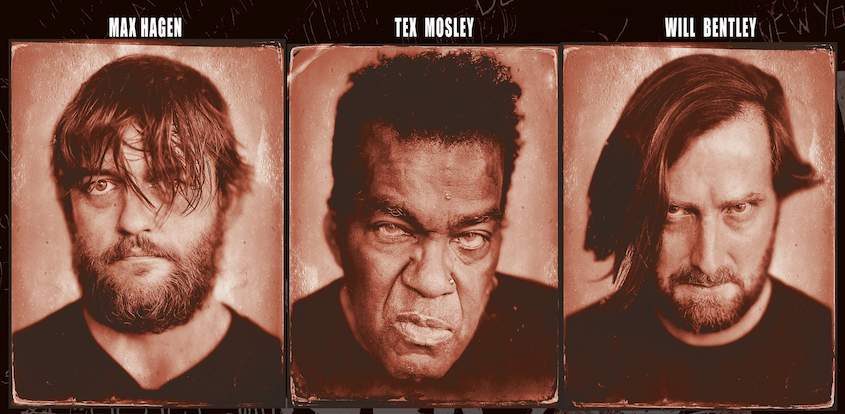

Tex Mosley of Neverland Ranch Davidians on Their New Album, ‘Shout It on the Mountain’

Neverland Ranch Davidians, the Los Angeles-based rock trio known for their electrifying live performances, recently released their second album, ‘Shout It on the Mountain,’ through Heavy Medication Records.

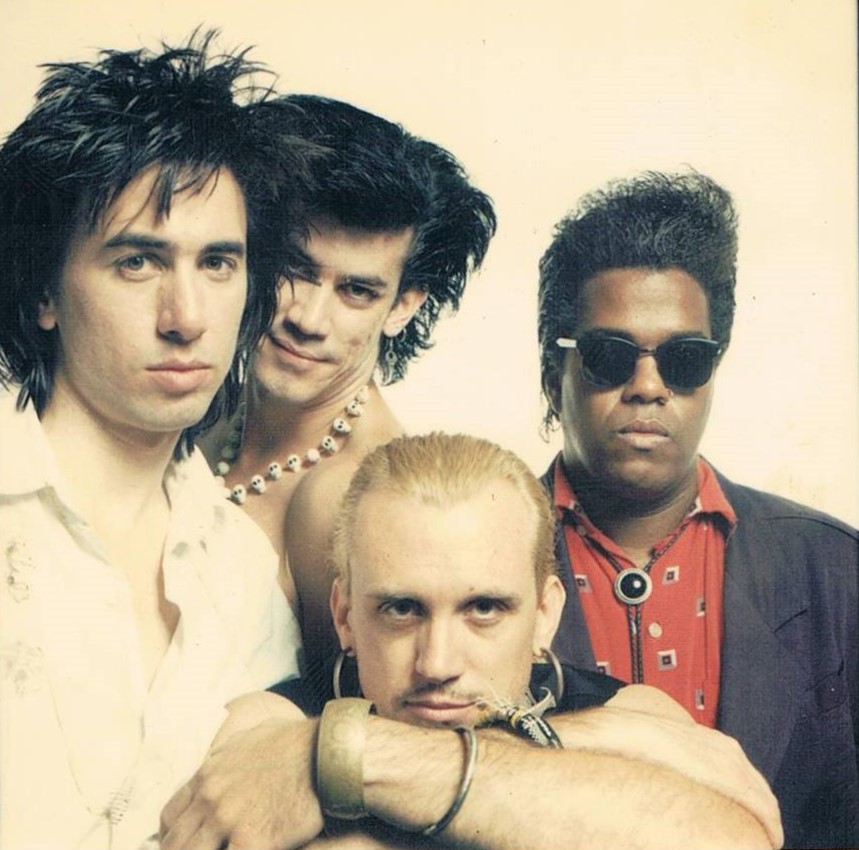

The album offers an intense fusion of punk, rhythm & blues, and rock. The trio—Tex Mosley (vocals, guitar), Will Bentley (guitar, backing vocals), and Max Hagen (drums, backing vocals)—is joined by Greg “Smog” Boaz (bass). While the band’s live performances traditionally exclude bass, Boaz’s contributions enrich the album’s sound. Mosley, a veteran of several influential punk bands, brings his eclectic influences, from Stax soul to cowpunk, into the mix. Shout It on the Mountain features original songs alongside covers like Eddie Floyd’s ‘Big Bird’ and Skip James’ ‘Hard Time Killin’ Floor Blues.’

“When we get together and are running on all cylinders, it’s like capturing lightning in a bottle”

Tex, the new album Shout It on the Mountain was recently released, and from what we’ve heard, it’s got this mix of punk, R&B, and even a bit of soul. When you write a song, do you start with a clear impression of where it will go musically, or does that develop during the process?

Tex Mosley: It really depends on what’s inspiring me at the moment. What I mainly do is come up with a blueprint or a general idea for a song, and then Will, who’s a big part of the creative process, fills it in and adds the icing on the cake. But it all starts with whatever’s inspiring me at the moment.

You’re obviously a student of music and have played all types of music. Do you find it fun to mix and match various genres?

Definitely, but I consider all those kinds of music that inspire me as part of the same musical universe because it’s all stripped down, it’s all rootsy, and it’s all rock & roll. I don’t think of them as separate genres because that’s not the way I look at music. I look at whether or not something moves me or what mood a certain piece of music evokes in me.

Do you ever feel like you are paying your respects to those who have gone before?

Without a doubt, whether it’s conscious or not. I can’t help but feel that what I do wouldn’t exist without those who came before me. Obviously, I put my own spin on it, but they gave me the building blocks. They’re all an inseparable part of my musical DNA.

‘Cactus Cooler Man’ is the first single from the album. Tell us about the vibe of the track. It feels like it’s got this retro, trashy, almost glam-punk thing going on. How did that one come together?

That song’s about a friend of mine, Sean Wheeler, frontman of the band Throw Rag. We’ve known each other for 20 or 30 years.

What is it about Sean that inspired you to write a song about him?

He’s such a unique character, and it’s his personality and what he does that shaped that song. Sean was desert rock before there ever was such a thing. In fact, he’s the desert personified and the embodiment of the underground. He’s been in music for over four decades, fronted a lot of different bands, and worked in a number of musical styles. Sean’s a legend, yet most people haven’t heard of him. He’s even featured in two documentaries about the desert rock scene.

It’s hard to pigeonhole him, which is what makes him so interesting. He’s got soul, he’s streetwise, and he’s a total character. I thought he deserved to have a song written about him.

Tell us about your bandmates, Will Bentley and Max Hagen. Why do you feel the three of you work well together?

When we get together and are running on all cylinders, it’s like capturing lightning in a bottle. You’ll know what I mean if you see us live.

I met Max 20 years ago when I was in rehab. Max was working there at the time, and we hit it off. He’s literally one of the best drummers you can get and a student of music. And I met Will Bentley through Max.

Will plays a huge role in the creative process, in the way our music evolves. We butt heads a lot, but he’s literally the glue that holds this all together musically. He’s a great musician, too.

Tell us a bit about your musical evolution. Did you start off learning acoustic guitar, or did you go straight into punk?

I was raised in a musical family. My uncle (my father’s brother) was a jazz musician and played with everyone from Sonny Stitt to Pat Martino. My grandfather played guitar and banjo in a bunch of bands, too.

When I was a kid, my sister had an acoustic guitar, and I just started playing around with it. From day one, I’ve always loved rock & roll. I was raised on it. It would be playing all the time on the radio—WIBG in Philadelphia, the Wee Willie Webber Show. He’d play Argent, The Sweet, Bowie, all of the great rock & roll from the ‘70s.

As I got older, I developed what I started leaning towards personally, like Iggy and the New York Dolls. I didn’t even understand what they were singing about then—the sex and drugs and so forth.

Over the decades, has there been anybody who directly influenced you, such as a formal teacher or one of your rock ‘n’ roll brethren?

That would be Michael “Spider” Sanders, the drummer of Pure Hell. He was a huge influence on me. I’d even say he was my number one influence.

Yes, tell us about your connection to the 1970s Afro-punk band Pure Hell.

Spider’s mom used to babysit me when I was a kid. I’d be over at their house, and Spider would come in all glammed up and rocked out. I was around 10 or 11 years old, and he was like a superhero to me! He started to let me hang out with him.

He would travel back and forth to New York. He was a staple of that first wave of the N.Y. underground. He even played with the New York Dolls, filling in when Jerry Nolan went into rehab. He played about four or five shows with them. Spider was the man!

And then The Dolls sort of took Pure Hell under their wings, and Pure Hell moved into The Dolls’ loft. When Spider would come back home to Philly, he’d be looking all glam and have new gear. I wanted to be him!

He’d steal his mom’s car and take me with him to New York City all the time. It was on those journeys that I got to know Johnny Thunders, Jerry Nolan, Lenny Kaye, Alan Vega… In fact, Alan Vega and Lenny Kaye would see me at gigs and ask, “What are you doing here?” Those were the times when a 14- or 15-year-old kid could get into a show.

How did your relationship with Pure Hell evolve?

I was friends with all of them; they lived in the neighborhood. I would hang out at singer Kenny “Stinker” Gordon’s house every day. I got really close with Lenny Boles (bassist) and Chip Morris (guitarist). This is even before they became Pure Hell.

They were called Pretty Poison back then and would perform all covers—from Silverhead’s ‘Long Legged Lisa’ to Bowie’s ‘Hang On to Yourself.’ Lenny was the singer then but later moved to bass, and Stinker became the singer. They were it! Imagine living in a lower-middle-class, all-Black neighborhood that was dangerous and gang-infested, and walking around in platform shoes, tight corduroy pants, and makeup. But that’s what I wanted to be!

I later played about five or six live shows with them after they reformed.

In the press materials, you state that this record has a stronger rhythm and blues influence than what you’ve done before. Was this something you always had in the back of your mind, or did it just sort of creep in during the process?

It’s what I’ve been inspired by, especially all the Stax Records stuff that I’ve been listening to a lot lately. I think it all sews together easily because if you take the music that Stax Records was doing and strip it down, it’s all garage—at least in my perception.

Will plays a huge part in bringing that R&B feel out in the Davidians’ music when he, like I said earlier, “puts the icing on the cake.”

To be honest, we’re not doing anything new. James Chance and Alan Vega were doing that a long, long time ago. I’m just carrying that torch. A lot of that old soul and R&B is literally garage once you strip it down and un-polish it.

You’ve said that R&B and punk rock are just two sides of the same rock ‘n’ roll coin. If you had to choose a defining moment where you saw this connection crystallize, what would it be? Was it something you learned along the way or something you just always knew?

I suppose that subconsciously, I always knew it. I’ve been into rock & roll my entire life, but in the background of my upbringing was a lot of R&B because that’s what everybody around me listened to. But I wasn’t really open to a lot of the “Black” music out there at that time because I wanted to be in Alice Cooper’s or David Bowie’s group—not realizing that they were being inspired by Black artists. Maybe it’s good that I wasn’t that into it as a kid; I had to mature into it.

Listen to Isaac Hayes’ version of ‘Walk On By.’ It’s an iconic soul track, but it’s total rock & roll. Same with Sly & The Family Stone’s ‘Sex Machine.’ Or Humble Pie’s ‘I Don’t Need No Doctor’—that’s their version of R&B. Or the song ‘Fun House’ by The Stooges; that’s just them deconstructing a James Brown groove. It’s all the same—punk rock, R&B, rock & roll. R&B just tends to be more polished, that’s all.

You’ve got a few covers on the new album—Eddie Floyd’s ‘Big Bird,’ Half Pint & the Fifths’ ‘Orphan Boy,’ and Skip James’ ‘Hard Time Killin’ Floor Blues.’ What made you choose these particular tracks, and how did you put your own spin on them while keeping their original fire intact?

‘Big Bird’ was Will’s idea; he wanted to do it. When I heard it, I thought, “This sounds like something we could have written.” ‘Orphan Boy,’ which is on one of the Back From the Grave compilations, was always one of my favorite songs that I wished I’d written. ‘Hard Time Killin’ Floor Blues’ is a song I love playing on acoustic guitar. I brought it into rehearsal one day, we started messing with it, and it materialized as it appears on the album, with Will writing a majority of the new lyrics.

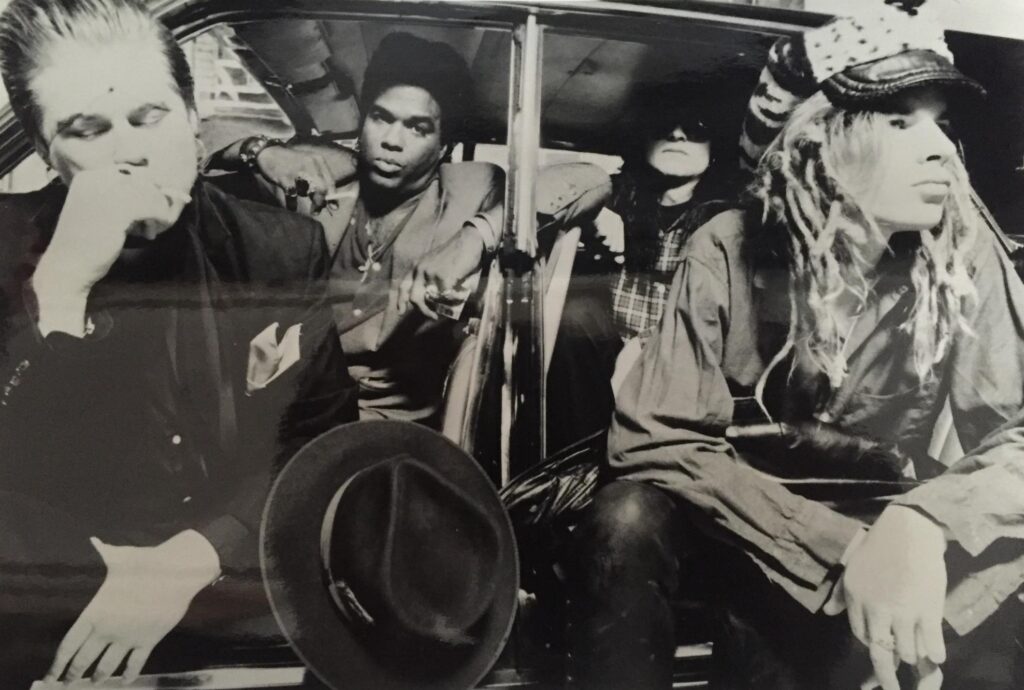

Before Neverland Ranch Davidians, you were in bands like Whores of Babylon (with Keith Morris), Bad Actor, the Slaves, and The Hangmen. You’ve got this long history with punk rock. What’s the biggest thing you learned back then that still sticks with you now? And how does that shape what you’re doing today with the Davidians?

I suppose it’s the frantic abandon, the streetwise attitude, and the sincerity of the underground that still resonate with me most. It’s what drew me to punk rock in the first place and still drives me to this day. Punk was all about being “real” and authentic, and that’s what I strive for in my music. A lot of Davidians’ songs are about things that happened to me throughout my life.

When Mike Martt of Tex & the Horseheads died in 2023, you took part in a memorial concert in his honor. Horseheads bassist Greg “Smog” Boaz also appears to be a friend of yours, and he’s on your new album. Tell us about how you became part of this band’s inner circle and what they mean to you.

Smog was one of the first people I met when I got to L.A. Being out West, I became infatuated with the driving out here. It was my first time traveling cross-country, and once we got to the desert region, I became obsessed with it—the cacti, the open highway surrounded by desert, the kind of thing I’d seen on TV as a kid. Then, when I got exposed to cowpunk, I thought, “Damn, this is my calling.” It just made more sense to me now that I was living in California. I knew Smog was a musician, but I had no idea he was playing cowpunk. Before I heard Tex & the Horseheads, I was into Lynyrd Skynyrd, The Outlaws, Molly Hatchet… the whole Southern rock thing.

I first saw Tex & the Horseheads at one of their rehearsals. Nicky Beat of the Weirdos had a rehearsal studio, and Tex & the Horseheads used to rehearse there. When I heard them, I felt, “Oh my god, this is where I belong!” That must have been in ’82, and I’ve been close to them ever since. I didn’t know then that they were a pillar of the cowpunk scene.

I have a Holy Triangle of Music—Gun Club’s at the top, and The Hangmen and Tex & the Horseheads are at the other two points of the triangle. And guess what? I’ve played with two out of three of those bands. That might not mean shit to anybody, but it’s a big achievement for me. It doesn’t get any better than those three.

I knew Jeffrey Lee Pierce, and the last time I saw him, Bryan Small (of The Hangmen) and I met him—I think it was at Sunset and Sweetzer. The Hangmen had recorded a cover of ‘Thunderhead,’ and I think we were meeting him to get his permission or to give him some money for it. And that was the last time I saw Jeffrey. He used to live in Westwood, and when I first got out here, I would hang out with Bob Ricketts and Harlan Hollander. They used to organize this softball thing in Westwood, and I’d see Jeffrey there. I used to hang out with Bob Ricketts all the time, and we even wound up living together for a while. When he got his own place in Hollywood, he’d have get-togethers every weekend, and I’d consistently see Jeffrey at those, too.

You’ve worked with some heavyweights over the years, from Suzi Quatro to Keith Morris. Out of all the collaborations, which ones stand out the most and why?

Those Suzi Quatro sessions for her In the Spotlight album were the best. I was in the Neighborhood Bullys then, and we were hired to be her backing band. I never got to meet her, unfortunately, because we recorded all the tracks in L.A., and she recorded her parts in Europe. But during those sessions, I spent a lot of time with record producer and songwriter Mike Chapman and had some very intense conversations with him. I was a fan of his work, and he was very approachable. I asked him about everything—from recording Suzi Quatro’s first album to all the stuff he did with The Sweet, from his Blondie sessions to co-writing “Simply the Best,” which Tina Turner had a huge hit with.

I also spent considerable time with Rob Younger of Radio Birdman when I was in The Hangmen. Rob had been hired to produce the second Hangmen album for Geffen Records, which never got released. It was going to be their follow-up to their awesome debut on Capitol. I spent about three months with Rob, and we became very close. He’s another guy who’s very approachable. We recorded with him for several weeks in L.A., then laid basic tracks with him in Memphis for a month and a half, and then I recorded all my guitar overdubs in Nashville. He wrote a blurb for the first Neverland Ranch Davidians album!

With a band name like Neverland Ranch Davidians, there’s gotta be a story behind that. How did the name come about, and what kind of vibe were you trying to evoke with it when you started the band?

My wife Patti and I came up with the name, and she came up with the New Orleans voodoo concept behind the band logo and our show flyers. We were trying to evoke something dark and mysterious yet absurd at the same time. Don’t get me wrong, I love Michael Jackson. But how twisted is it to associate him with the Branch Davidians?

“I also think music used to be more fresh.”

You grew up in Philadelphia, but you’ve spent most of your life in L.A. What was it about the city that made you settle there? Did it have that magnetism you hear about, or was it more like, “I’m here, and now let’s see what happens”?

When Pure Hell stopped playing, Spider Sanders joined this band I’d started called Bad Actor. We wound up touring with the Circle Jerks, which is how Spider and I wound up in L.A. That was 1981.

At that time, L.A. was ground zero for rock & roll. You had everything going on over here—punk rock, rockabilly, ska, metal, cowpunk… the music scene here was thriving. Think about it: you had Black Flag, the Minutemen, Circle Jerks, X, Fear, Red Scare, The Weirdos, The Dils, The Dickies—all of that was happening at once. The Screamers had already broken up, and Darby Crash was already dead when I got out here. So any night of the week, you could go see great bands like that. Why would I want to leave? Incidentally, that’s also when I met the now-legendary punk rock photographer Ed Colver. He photographed the Davidians for both of our album covers.

I was fortunate, though, because when I lived in Philly, I got to see the Bloodless Pharoahs (with Brian Setzer), Dead Boys, Ultravox, Buzzcocks, Madness, Ramones, Sic Fucks, Suicide… I got to see the first wave of the New York underground. And don’t ask me how, but those were the days when an underage kid could get into a club.

L.A.’s live music scene, especially in the ’80s and ’90s, was a wild ride. From your perspective, what’s the biggest difference between the scene then and now?

Technology has changed things a lot. First of all, there’s a lot more music out there, thanks to technology. Now everyone can record a few songs at their rehearsal space and put them up on Bandcamp the same day. I’m not saying there’s not good music out there nowadays, but you have to spend more time finding the cool stuff.

Secondly, technology has made us more connected than ever before on a certain level, but a lot of that connection is virtual, so people have gotten accustomed to not going out as much anymore. You see that in the decreasing number of people at concerts in small venues. Bigger bands will still draw a decent-sized crowd, but lesser-known bands in the smaller venues don’t attract as many people. Audiences at rock & roll concerts have gotten older too, at least in L.A.

I also think music used to be more fresh. There was a lot more to pick from back then as opposed to now. A lot of music today is trying to sound like something that came before it. When punk started, it was a certain approach to music, not a style of music per se, and so it drew from a wide range of influences, which yielded a bigger variety of bands. I mean, look at the variety you used to have. You had The Jam, Magazine, Television, Suicide… all bands that had their own sound. Now, a lot of punk is drawing on punk that came before it, which makes it less interesting.

It’s like when you make a photocopy of something. Once it’s been copied x amount of times, it becomes faded and less interesting. Back then, no one was trying to sound like The Heartbreakers. They had their own sound, and now people are trying to emulate that sound. Some might add their own spin on it, but it still sounds sort of familiar. The genre’s eating its own tail.

There’s still a lot of great stuff out there, for sure, but it’s fewer and farther between. Or maybe that’s just me getting older.

Are there any hidden gems—either musicians or music venues—in L.A. that you would recommend our readers check out?

Venue-wise, there aren’t that many places to play. You’ve got The Redwood, Maui’s Sugar Mill, and Alex’s in Long Beach. Musically, you’ve got (ex-Lazy Cowgirl) Pat Todd & the Rankoutsiders, whom I love dearly and who are one of the very best bands in L.A. You also have Tramp for the Lord, an alt-country band fronted by Doug Cox, who was the bass player in The Hangmen on their first album and also happens to be an incredible songwriter. I’ve started playing in that band recently, and they’ve got a great debut album coming out this spring on Heavy Medication Records, who also put out the Davidians.

When you look back on your career, is there one specific moment or show that stands out as the one that you’d say was your “breakthrough” moment, even if it wasn’t recognized at the time?

I think one of the biggest highlights of my career was being in The Hangmen, from around 1990 or ‘91 to ’97. Bryan Small is a genius of a songwriter, and he still cranks out amazing songs. The Hangmen left an indelible mark on me, and it’s a badge of honor for me to be a part of that band’s history. In 2023, I filled in for Jimmy James for nine shows on their West Coast tour, and it was exciting to be up on stage with them again. It was like riding a bicycle after not having ridden one in a long time—you never forget. It took me just hours to dial back into that style of playing. I gave that West Coast cowpunk an East Coast flavor.

Another great moment in my musical history was playing with a second songwriting genius, Rik L. Rik, in The Slaves. Rik had seen Bad Actor and asked me to play a few shows with him in ‘86. He later formed a band called Flesh & Blood, which became The Slaves, and asked me to join them. It was like backing Bryan Ferry, David Bowie, and Nico all rolled into one. We only recorded that one album for I.R.S. Records in 1990, a deal that Johnette from Concrete Blonde helped us get. I still love that record to this day.

What are your plans for 2025 and beyond? Will we see touring with Neverland Ranch Davidians, or are you diving into any other musical adventures in the pipeline?

Hopefully, the Davidians will be able to play in Europe this year, and we’ll be playing a lot more in the U.S. We’ve already got songs written for the next album, and maybe we’ll see an EP materialize later in the year.

As I mentioned earlier, I’ve also been playing with Tramp for the Lord, and their debut album’s coming out soon. It’s called Seven Clouds of Joy. The material was recorded before I joined the band, but I’m looking forward to playing those songs live and promoting the album. If you like desert-fried outlaw country, you’ll want to check it out. Doug Cox is a very gifted singer and songwriter.

Do you have any interests outside of music?

Making sure I live long enough to see my daughter turn 18 and keeping my family secure. Outside of music, they’re my main priority.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Ed Colver

Neverland Ranch Davidians Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp

Heavy Medication Records Website / Facebook / Instagram / YouTube / Bandcamp