Wolfgang Seidel on His New Book “Krautrock Eruption” and Ton Steine Scherben

Krautrock Eruption offers an invaluable, firsthand account of one of the most revolutionary musical movements of the 20th century.

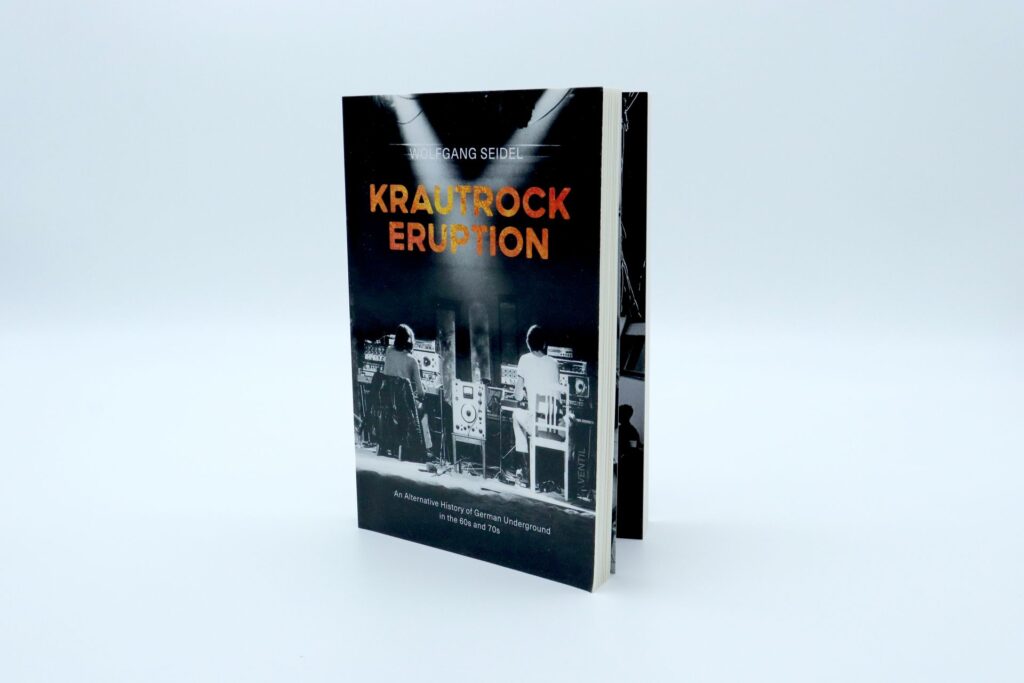

Written by Wolfgang Seidel, a central figure in the German underground scene—both as a member of Conrad Schnitzler’s band Eruption and a co-founder of the renowned Ton Steine Scherben—this book provides readers with an intimate look at the cultural, political, and social forces that gave rise to Krautrock. Seidel’s memoir paints a vivid picture of post-war Germany in the 1960s and ’70s, a period marked by profound societal and political upheaval. His narrative immerses us in the world of protests, squats, and impromptu concerts that shaped the music of legendary acts like Cluster, Tangerine Dream, and Ash Ra Tempel.

Seidel’s perspective is unique, as he lived through these creative times, offering rare insights into the development of this experimental music. He was there from the start and doesn’t sugarcoat it. His writing reads like a series of live-wire memories, laced with passion and intensity, as he paints a vivid picture of a country desperate to shed its shackles—and a scene all too eager to oblige. His narrative emphasizes the youth’s desire to break free from the constraints of post-war Germany and create something wholly new.

What makes Krautrock Eruption particularly compelling is its focus on the intersection between minimalist classical composers, like Steve Reich and Philip Glass, and the emerging use of synthesizers in experimental rock. This fusion of genres, within the context of Germany’s post-war climate, created a perfect storm of sonic experimentation.

Alongside the memoir, the book includes a detailed discography curated by Krautrock expert Holger Adam, which serves as an excellent guide to the genre’s essential albums. This book is an indispensable resource for anyone seeking to understand the origins and impact of German experimental music.

Krautrock Eruption is available for pre-order here.

“To describe Krautrock as a rejection of the German past is correct”

You describe your fascination with your aunt’s radio as a portal to a world beyond post-war Germany. How did this sense of longing shape your musical journey and eventual participation in the countercultural movement of the 1960s and ’70s?

Wolfgang Seidel: The fascination with radio technology was not something specifically German. And it wasn’t the actual radio program that created this fascination. It was the interferences with its previously unheard sounds that created an awareness of the distance between transmitter and receiver—something that is lost with digitalization. The radio, which had somehow found its way from the possession of a U.S. soldier stationed in West Germany to my aunt’s flat, was something special for me as a child because, in addition to its shortwave reception with all of its disturbances, it also had a much more modern design than the devices I knew. The radios produced in Germany hid the technology in a conservative design that made them look like an old-fashioned piece of furniture, hiding their advanced technology as if it were something to be afraid of. In this contradiction between advanced technology and backward-looking design, however, you can actually see something specific to the German postwar mindset.

Your book presents an alternative history of Krautrock, moving away from the usual narratives. What are the biggest misconceptions about the movement that you aimed to correct?

I wouldn’t call it an alternative history. I try to add the social background to the usual narrative—the situation the young had to face. Today’s texts about Krautrock often read like a success story. With a few exceptions, Krautrock was not. The success of Kraftwerk, for example, came when the time for Krautrock was actually over. Kraftwerk are now seen as a blueprint for Krautrock, but the movement was much more diverse and full of contradictions.

Krautrock has often been framed as a rejection of Germany’s past, yet it also engaged with the country’s unique social and political climate. How do you see the balance between escape and engagement in the music of that time?

To describe Krautrock as a rejection of the German past is correct—if you limit the past to the Third Reich and the years 1933–1945. The rejection of this chapter was a consensus. When it came to the present and the future, the spectrum was more diverse—just like the music, which ranged from romanticized exoticism (Embryo) to references to Bauhaus and constructivism (Kraftwerk) to a glorified Middle Ages (Ougenweide).

If you had asked the musicians how they categorized themselves in the political coordinate system, many of them would have answered: left-wing or socialist—only to immediately clarify that this did not mean the kind of socialism that was dominant in the GDR, which was seen for what it was: an authoritarian regime. The contradictory political positioning of Krautrock was demonstrated by the criticism of Western society, of which the Federal Republic had become a part, as a consumer society. This ignored the fact that pop music—and Krautrock as part of it—would not have been possible without the financial and technical resources of this consumer society.

“Resistance to mainstream society could take various forms”

You were a co-founder of Ton Steine Scherben, a band deeply connected to political activism. How did that experience influence your understanding of the intersection between music and resistance?

That’s funny. When Krautrock emerged at the end of the ’60s and peaked in the first half of the ’70s, Ton Steine Scherben weren’t counted as Krautrock. The band was one of the first to start singing in German while most of the other bands sang in English or had no lyrics at all. Fans and musicians wanted to distance themselves from the past by avoiding the German language. But musically, Ton Steine Scherben were a rock band with English or U.S. role models.

Resistance to mainstream society could take various forms: living in a commune instead of the bourgeois nuclear family, working collectively without hierarchy, or squatting—either to live in or to create alternative communication spaces. Many of the Krautrock bands, known and even more unknown, tried to be active in one of these fields. The Scherben tried everything at the same time—for example, by distributing their records themselves and living in a commune in an old farmhouse.

In their youthful enthusiasm, the Scherben had announced that they would play everywhere in support of political campaigns, without thinking about the fact that they needed at least the petrol for their band bus. When they mentioned that at least the expenses had to be covered, there were often raised eyebrows and accusations of being on a “capitalist trip.”

The book suggests that Krautrock was more than just a musical movement—it was an artistic and political statement. How do you see the relationship between squat culture, demonstrations, and the music itself?

Besides playing solidarity concerts, writing political lyrics, and having an alternative lifestyle—living in a commune—where might the interfaces between music and progressive social movements be in the music itself?

Alfred Harth, whose musical career began with free jazz at the end of the 1960s and who played with Fred Frith, Chris Cutler, John Zorn, and Lindsay Cooper in the 1980s, coined the term herrschaftsfreie Musik (“music without dominance”). Although the term has not caught on, it is ideally suited to describe the utopian content of Can’s music, for example. In a society that, three decades earlier, had followed the orders of the Führer, having no one giving orders was opposition without words. In this, Krautrock followed German free jazz, which was more radical than in other countries.

You write about the influence of minimal music composers like Steve Reich and Philip Glass on Krautrock. How do you think their repetitive structures and phasing techniques resonated with the spirit of German underground music?

I don’t know if this influence is more or less name-dropping. A reaction to both: the strict determinism of serial music and the unpredictability of improvisation. Perhaps minimalism was the perfect music for a state of exhaustion that came with the end of the most rebellious phase at the end of the ’60s.

The book features rare photographs and a discography by Holger Adam. What role do these elements play in shaping the reader’s experience of Krautrock’s history?

I was not involved in the image research. My contributions are the photos I found in Conrad Schnitzler’s archive.

What I like about many of the photos is that they show the simple technical means with which the bands realized their ideas. Later pictures of Tangerine Dream or Klaus Schulze show the musicians disappearing behind walls of synthesizers. The beginning of their careers was much more modest: electric guitar and drums. And the will to do something new.

In compiling this counter-narrative, were there any stories or perspectives that surprised you, even as someone who lived through it?

There are very few written documents from the time when Krautrock was forming. TV interviews are also rare. Reports in television culture magazines are often characterized by great mistrust on the part of the makers, who saw them as products of the culture industry. The majority of texts or TV documentaries about Krautrock have been produced in recent years. They all have the problem of sparse sources. Interviews with contemporary witnesses should be treated with caution. There is a risk that interviews with contemporary witnesses say more about today than about yesterday—how they wish yesterday had been. That’s why I didn’t use interviews. The quotes that appear in the book are from the hot phase of Krautrock.

“When the term “Krautrock” appeared for the first time, it was seen as the insult it was.”

The term “Krautrock” itself was originally a British invention. How did musicians within the scene feel about this label at the time? Did it ever influence the way the music was perceived internationally?

As I said, Ton Steine Scherben were not counted as Krautrock for a long time. If you leave the German lyrics aside, they were probably the most English or American band in the Krautrock universe. They often saw the other bands as too escapist. The Scherben’s role models were bands like MC5. When the term “Krautrock” appeared for the first time, it was seen as the insult it was. After a while, the German musicians accepted it as irony. The opening track of Faust’s album for the British label Virgin was named ‘Krautrock.’

Your involvement with Eruption placed you at the heart of one of the most experimental corners of the scene. What was the creative process like in a group that embraced such a radical approach to sound?

I found myself “at the centre of one of the most experimental corners of the scene”? I didn’t notice much of that at the time. We were sitting in an unheated former ballroom. There were sessions with different participants. The only trace that these sessions have left behind are two audio tapes. They’re interesting because they don’t sound much different from some of the free improvisation that goes on in the improviser scene today. Did we have a plan? No. We just went for it. And the rather random presence of the participants led to different results. None of the participants would have thought that these sessions would attract attention decades later. I certainly didn’t.

The synthesizer played a significant role in shaping the sonic identity of Krautrock. How did German musicians approach electronic instruments differently from their counterparts in the UK or the US?

In the beginning, nobody had one—except for one exception: Florian Fricke. He had the financial means to buy a Moog system, which was featured on the cover of the first Popol Vuh album. Around the same time, Wolfgang Dauner also used a synthesizer. Although Tangerine Dream’s first LP was called ‘Electronic Meditation,’ there is no synthesizer. What you hear is electric guitar, drums, cello, violin, and all kinds of objects inspired by Musique Concrète. The closest thing to a synthesizer were the so-called combo organs by Italian manufacturer Farfisa.

In the ’70s, synthesizers became more affordable but were still expensive. What you can see is that there were two “schools” in how to integrate these new instruments into music. On one side were the trained keyboardists who played conventional melodies with sounds that resembled strings and brass. The other school saw the synthesizer as a source of sounds never heard before, which demanded new ways of composing.

Looking at today’s electronic and experimental music scenes, where do you see the strongest echoes of the Krautrock ethos?

Berlin has become a centre of improvised music in the last two decades. The music ranges from free jazz and Neue Musik to electro-acoustic and electronic music reminiscent of the sounds of early Kluster/Cluster recordings. This scene gathers under the term “Echtzeitmusik” because what the musicians have in common is that the music is composed in real-time.

For me, it’s not just the sound aesthetics that feel like déjà vu. I find the return of free improvisation interesting, as it long received little attention. Perhaps because too much music had become too predictable? Although—even free improvisation is not free of clichés. What I also like is the return of a musical Arte Povera. It is refreshing to see a return to cheap DIY sound generators and objects like those used by Kluster. For me, it’s a déjà vu. You don’t have to invest lots of money to make music.

The release of ‘VA – Krautrock Eruption’ as an accompaniment to your book suggests an ongoing interest in this music. Why do you think Krautrock continues to resonate with new generations?

I don’t know if there is this “enduring interest.” When I hear of today’s bands being influenced by Krautrock, it usually means mostly Kraftwerk or Neu as their blueprint. But Kraftwerk and Neu are only one of many facets of Krautrock. With Kraftwerk, you also have to ask: which period in the band’s history is meant?

On the other hand, there are the aforementioned musicians from the Echtzeit scene, who have often never heard the term Krautrock but are much closer to radical, non-commercial experimentation. I have to say that the compilation published by Bureau B to accompany the book, with its 12 tracks, leaves large gaps—for a reason: the original Krautrockers didn’t make it easy for record producers with their penchant for tracks not under 20 minutes in length—the playing time of an LP side. And even that was seen as a compromise.

Bureau B has been instrumental in reissuing and curating significant works from this era. How do you feel about the role of archival labels in shaping the legacy of underground movements?

Even though it’s annoying for the musicians and labels because they don’t earn anything, you can find (almost) everything on the internet. But that doesn’t make the work of labels superfluous. If someone likes a piece of music, the listener wants to know more about the band, the genesis of the music—the place, the time, the musicians. A good label brings you all this information. And is there a more suitable place for this than the record sleeve? There is also lots of music in private archives that would never see the light of day without the research of record labels.

If you could recommend one lesser-known Krautrock record to someone just beginning their exploration, what would it be and why?

I’m not a record collector. I have the privilege of living in a city where there are concerts in small clubs almost every night, where you can talk to the musicians afterward. If I were a record collector, I would now prove my “expertise” by naming records that no one has ever heard of and that are extremely rare. What I can recommend as an introduction to Krautrock are the albums by Can—from ‘Monster Movie’ to ‘Future Days.’ If that’s too rocky for you, I recommend Cluster: more precisely, ‘Cluster 71,’ which is the first LP without Conrad Schnitzler (hence the name change from Kluster to Cluster). It still confronts the listener with the radical free sounds of the time when the band was still called Kluster—only with better recording technology. I’m always amazed at how timeless the record is. After that, Cluster’s music became easier to consume—which is a kind way of saying more boring. That’s the problem with Krautrock releases in general. Often the bands only left behind one interesting record. Usually, it was their first. Amon Düül II is an example of this. ‘Phallus Dei’ is still worth listening to. After that, they turned more and more into one of many rock bands. But this is my personal opinion that shouldn’t stop anyone from going on a voyage of discovery themselves.

Krautrock was often about breaking boundaries. What boundaries do you think still need to be broken in music today?

I wish I knew the answer. Even the aforementioned Echtzeitmusik doesn’t break any barriers. The musical avant-garde largely lives on government funding. That’s certainly not the proof of how subversive this music is. For me, music has always been interesting as a social activity. Social activity requires several participants—e.g., a band and its audience. Bands hardly seem to exist anymore, at least in the charts. The charts are dominated by solo artists whose music is created with the latest computer technology and perhaps the help of a few studio musicians. The debates surrounding the use of artificial intelligence in music production do not offer any hope of improvement. Perhaps we are experiencing a renaissance of live music—not gigantic stadium concerts but smaller formats with not much distance between musicians and audience.

Having lived through both the original movement and its retrospectives, how has your own understanding of Krautrock evolved over time?

I am not very interested in the retrospectives. They didn’t bring me much that is new. It became boring when records that had been forgotten for good reason were once again brought onto the market as essential for every Krautrock collection.

Growing up in West Berlin during such a transformative time, how did your personal experiences shape the political and musical vision of Ton Steine Scherben?

As I said, there was some distance between Ton Steine Scherben and the majority of Krautrock bands. It was the next generation of German bands who referenced the Scherben. Blixa Bargeld of Einstürzende Neubauten and Rio Reiser, frontman of Ton Steine Scherben, became friends. Ton Steine Scherben became seen as the German adaptation of punk before there was punk. And Scherben have been the forerunner of independent record labels.

“Ton Steine Scherben was a spontaneous idea”

There are a couple of stories about how the band got its name—one linked to Heinrich Schliemann’s quote and another born from a spontaneous brainstorm. What do you think the name really represents, and how does it capture the spirit of the band?

Ton Steine Scherben began as part of a group of apprentices who articulated their problems and political demands in their theatre plays, some of which were performed on the street, in front of factories: better payment, better training conditions, housing. This was a political agenda that was much more rooted in daily life than the abstract discussions of the academic left. Most of the members of the Rote Steine (the name of the group) had an apprenticeship in the building industry. Their trade union, which they criticised for cuddling up to the employers, was IG Bau, Steine, Erden. Ton Steine Scherben was a spontaneous idea that arose from making jokes with the union’s name.

The early tracks like ‘Macht kaputt, was euch kaputt macht’ and ‘Wir streiken’ came off the back of pure frustration. What was the creative process behind these songs, and how did you envision their impact on society?

A lot of music was and is born out of pure frustration, from The Who’s ‘My Generation’ and The Sex Pistols’ ‘Anarchy in the UK’ to Nirvana’s ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit.’ The creative process for the lyrics was often triggered by the plays of the Rote Steine and the discussions they had with the theater’s audience. Ton Steine Scherben played a lot at squatters’ events. The concerts were often used to gather enough supporters in one place in preparation for such a squat. The first squats had mainly been the initiative of young workers and apprentices. For them, having a space to communicate and/or to live without being controlled by the authorities was more important than it was for students. As far as the impact on society is concerned: the “Lehrlingsbewegung” is mostly overshadowed by the student movement of the time, but it had some success in improving the situation of young workers and apprentices.

That legendary first performance at the Love-and-Peace-Festival on Fehmarn, with its unforgettable moments like the burning stage, blurred the lines between art and protest. What did those chaotic scenes mean to you, both at the time and in retrospect?

The truth is: we read about all this in the newspaper.

Launching your own independent label, David Volksmund Produktion, was a bold step away from the mainstream music industry. How did this move affect your creative freedom, and what challenges did you face as you navigated that independence?

Was the David Volksmund production “a bold step away from the mainstream music industry”? We would have liked to become the new mainstream. And unlike many Krautrockers, Ton Steine Scherben were musically in the rock and roll genre, which had long been mainstream at the time. The difference was that we didn’t have to deal with the objections of a management that was afraid that such radical lyrics wouldn’t be played on the radio.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

Most memorable concert? I remember one. The band was still a trio, without a name, as part of the theatre group Rote Steine. We played in Cologne in the hall of a youth center where the colorful products of a batik workshop were hung all around. So many colors – and the band was completely stoned. The few songs (perhaps only one?) we played felt like they lasted for hours. That’s when we were closest to Krautrock. What else do I remember? A concert at the Technical University that was organized by one of the many newly founded communist parties. The Scherben were supposed to provide some kind of “human touch” needed to attract a young audience in particular. We were expected to play songs that called the masses to battle: ‘Macht kaputt, was euch kaputt macht,’ ‘Der Kampf geht weiter.’ We felt we had already played these songs too often to have any fun with them, so we opened the concert with Little Richard’s ‘Tutti Frutti.’ This was an affront to the organizers, for whom the ideological core of their kind of “left” was simply anti-Americanism. When the situation escalated into insults like “Yank servants,” Rio Reiser, the band’s frontman, took his guitar and hurled it into the audience. Fortunately, nobody was hurt.

If we were to sit down and listen to ‘Warum geht es mir so dreckig?’ and ‘Keine Macht für Niemand,’ what would be some of the strongest memories from recording them, working on the songs, etc.? We’d love to hear about some further insight into those special recordings.

The first single (‘Macht kaputt, was euch kaputt macht’) was de facto a live recording. Rote Steine and friends had been the audience. The first LP was recorded in a small studio without this kind of support. That didn’t work – we missed the audience. So we decided to use a live recording for one side of the LP. That was a good idea, and in retrospect, I think we should have done the same with the other songs. On the fourth album, I was back on some of the songs. Unfortunately, as much as the songwriting had matured, the handling of the recording equipment, which the band had only recently acquired, had not. That’s a pity; the songs deserved a better production.

Klemen Breznikar

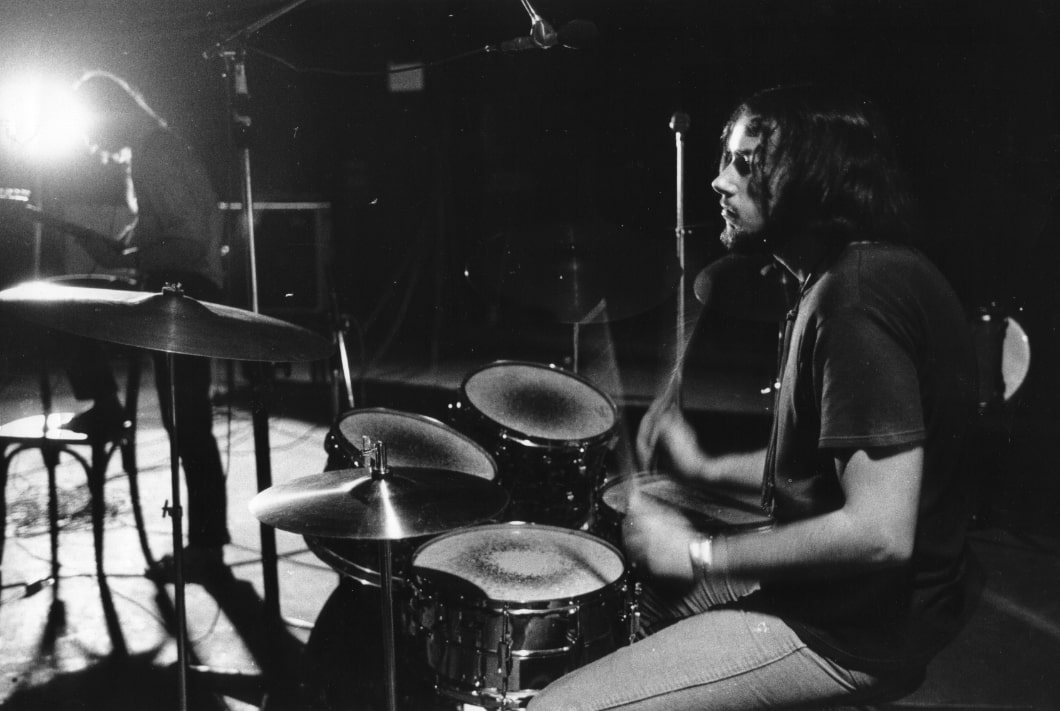

Headline photo: Wolfgang Seidel recording with Ton Steine Scherben (1971) | Photo by Jutta Matthes

Bureau B Website / Facebook / Instagram / YouTube / Bandcamp

Although Seidel comes across as a little touchy and poker-faced this is a good and informative interview. The book should be interesting coming from an actual German witness to the great scene.