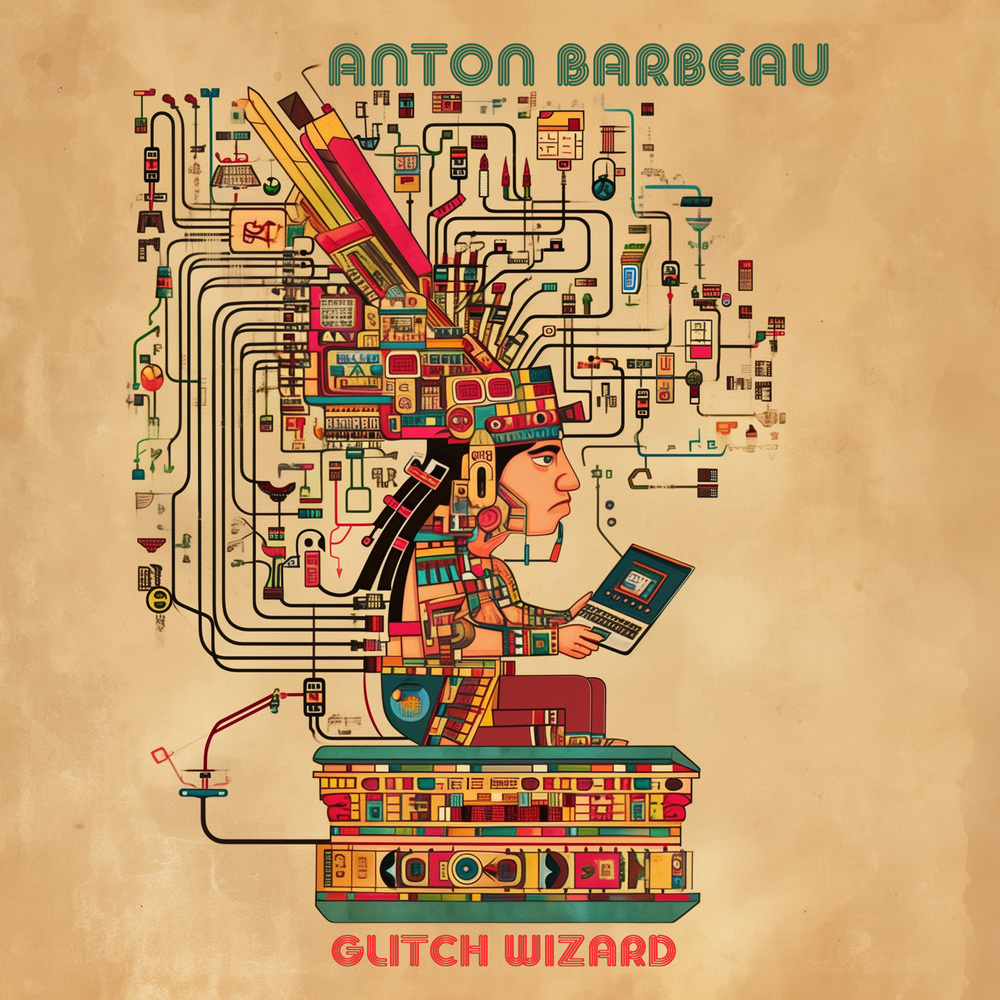

Anton Barbeau’s Double Drop: Track Premiere of ‘Glitch Wizard’ and a Deep Dive into His Double Release

Anton Barbeau’s ‘Glitch Wizard’ is the sound of a soul wrestling with grief, memory, and a fixation on things that flicker between the cracks of reality.

The title track is the first spell cast from his new album, an introspective journey through a fractured landscape of psych-pop and kraut-folk, made in the shadow of personal loss. Recorded in Barbeau’s “Dark Mystery Temple,” a basement studio that doubles as both creative space and refuge, the track is a swirl of hazy textures, shimmering guitar lines, and undulating rhythms. It is an emotional exorcism that channels both the weight of sorrow and the trippy escapism that accompanies it.

Barbeau’s father, whose final moments were spent in the adjacent room, is an invisible but powerful presence in these recordings, influencing every note with the rawness of final goodbyes. The music feels almost haunted, like something born from the tension between holding on and letting go.

The crew Barbeau’s got on this one include Dave Gregory, Andy Metcalfe, and Donald Ross Skinner. If you like your pop with a little bit of weirdness, a touch of melancholy, and a hint of something otherworldly, this one’s for you. It’s messy, vulnerable, and it sticks with you long after the track ends. This is Barbeau at his most real, and that’s what gives ‘Glitch Wizard’ its heart.

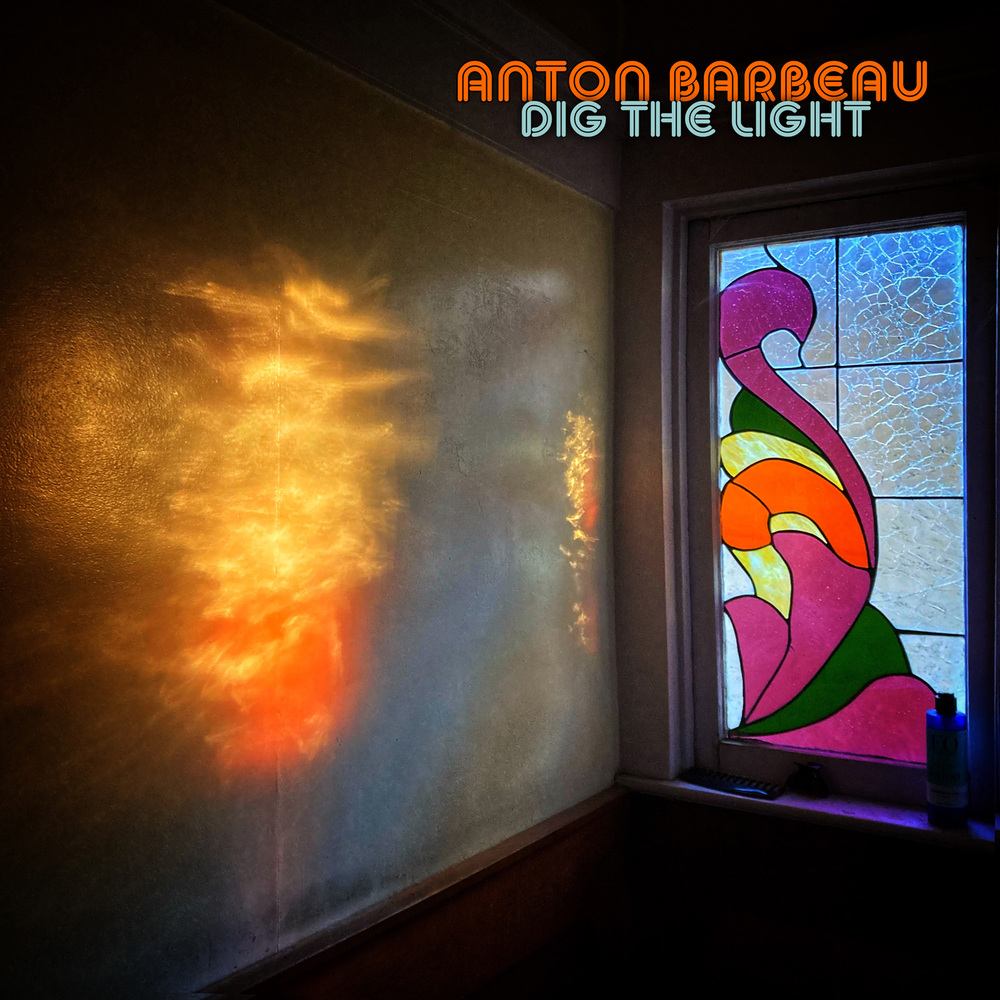

‘Glitch Wizard’ drops on July 11, 2025, via Think Like A Key Music, and that’s not all, there’s another one coming your way on the same day, ‘Dig The Light.’ Double the trouble, double the magic!

Pre-order ‘Glitch Wizard’ and ‘Dig The Light’ now and get ready for the double drop!

“Haunted is a good word for the album”

‘Glitch Wizard’ seems to be haunted by both personal loss and sonic anomalies, almost as if the album is actively short-circuiting itself while trying to make sense of things. In what ways did the “glitch”—whether as a sonic choice or a psychological state—become a central metaphor for this album? Did grief itself feel like a glitch in your reality?

Anton Barbeau: Haunted is a good word for the album. There’s a spirit to it that isn’t only mine. Some of my albums begin with a clear spark of inspiration which guides every step, beginning to end. ‘Glitch Wizard’ started off as “Garbage & Lucky Charms” and was NOT one of those inspired albums! It was originally comprised of fragments and scraps and miniatures. VERY slowly, it started to reshape itself.

I was writing songs at my dad’s house in his final weeks. He’d be in his room, smoking and watching TV with the volume up full blast. You can hear his television coming through some of my tracks, even. His death was actually very peaceful. He and I had become close in a new way from the moment he began hospice, even having the classic heart-to-heart talk just like in the films.

The title track to ‘Glitch Wizard’ was originally called “Black Candle,” and was written just after dad’s funeral. I began having a series of mystical experiences around that time, and the song—and the album—began a transformation into what we now have before us. Those experiences were indeed quite “glitchy,” with the rug of reality kinda being yanked from beneath my feet… if I can even claim my own feet as mine, man! The song ‘Glitch Wizard’ speaks to those early, bewildering mystical experiences, while the closing track, ‘A Pattern Forming,’ sees me in a more comfortable place and able to integrate new information within a now-familiar context.

My father died just over a year ago, and while elder care itself was sometimes incredibly stressful, once he started hospice, everything softened between us. His death, honestly, was peaceful and beautiful—and a relief. I’d expected to be knocked down by grief, but instead, I saw how natural it was for him. A friend described it as “the most perfect death she’d ever heard of.” Right down to my dad and I having the heart-to-heart talk just like in the films, days before he died. I was living with him 24/7 in the month of his death and I’d write a song a night while he’d be in his room, smoking and watching TV with the volume on full blast. Some of those songs are on ‘Glitch Wizard’ and even incorporate the background sound coming from his room. This record, it’s been noted, is certainly a darkness-into-the-light trip. After my dad’s death, I began having a series of mystical experiences, which indeed had a very glitchy nature. I wanted to incorporate this glitchiness into the sonic landscape of the album, finding ways to randomize sounds. The title track speaks directly to the experience of being pulled from one world to another and back again, where elements of “normal reality” vanish and a new mode of being—or non-being—occurs.

Your basement studio, Dark Mystery Temple, seems to function almost as a sentient entity in your recent recordings. With its name alone, it sounds like both a sanctuary and a place of creative exorcism. How much do you think the room itself dictated the sonic direction of ‘Glitch Wizard’ and ‘Dig The Light’? Could these albums have existed in a different space, or did the walls hold something specific that made them possible?

Many of the mystical experiences I mentioned have taken place in the Dark Mystery Temple. And the recordings I’ve done down there are very much a product of that space… there really is something special about it. For one thing, it has a “sound.” I’ve been fortunate to record at Abbey Road, and the first thing I did there was clap my hands. I knew the reverberant sound of that space down to the guts of my heart, right? The fact that Dark Mystery Temple has its own sound is important… instruments and vocals are contained and flavored in a very certain way in that space. The bass player in my band Klaust says, “it’s just the right size.” It fits four or five people comfortably. It’s cozy but not cramped. And… it has vibe! I’d say that the bulk of both albums were written in the same place they were recorded. In one corner, against a very bright orange wall, is the sofa I sit on when songwriting. In the opposite corner is my recording setup. Each of these spots has an energy of its own.

You’ve mentioned an “unhealthy” Steely Dan obsession during the making of ‘Glitch Wizard.’ While their music is often seen as pristine and meticulously polished, your album thrives on raw edges and ghostly imperfections. Were you drawn to them as a kind of unreachable ideal, or was your interpretation more about warping their glossy perfection into something more cracked and human?

Earlier in my musical life, I wore influences on my sleeve—and on my socks and trousers. If I got deep into an artist, I often reflected that back with a song or two. Not that it was always obvious to others. After having made soooooo many albums, I’m sure I’m my own influence more than anyone else. My ‘Manbird’ album, say, was created during my obsession with both ABBA and Fleetwood Mac, but it sounds like extra-mega ‘me’ to me.

I’ve become a big Steely Dan fan of late and have added ‘Aja’ to my small stack of lifetime favs, up there with ‘Sgt. Pepper’ and ‘Jehovahkill’. I love the absolute perfectness of SD’s recordings. But I’m so far from that kind of mindset. I was a very annoying—and clueless—control freak in my first days making records. Now, with all the software in the world, it’s somewhat easy to do startling, fanciful things with music, but at the same time, I’m trying to get a good first take. The raw, real thing. Maybe it’s the collective fried attention span, but I don’t have it in me to try for Steely Dan righteousness. And, honestly, my fantasy “perfect” Anton album would be more ABBA anyway.

Having Dave Gregory (XTC) and Andy Metcalfe (Soft Boys) in the mix feels like a lineage moment, two musicians who helped bridge classic psychedelia with the sharp corners of new wave. Given your own blend of psych-pop and krautfolk, do you feel like you’re carrying their torch in some way, or do you see your work as diverging into something they never quite ventured into?

Let’s add Donald Ross Skinner to that list… these are all people who were part of records that changed my life, that shaped me. And yeah, I see my work as carrying on a certain psychedelic-pop tradition. The guys we’re speaking of each have such distinctive voices. You hear an Andy Metcalfe bassline, you know it’s him. How personality translates directly through music will eternally fascinate me… that’s a form of magic, to extend one’s essence into a stick with strings and make that stick sing for the world? Yow. Am I doing anything unique or different from my heroes? Sure, but I don’t think what I’m doing is meant to have the same level of impact. My songs are always pretty personal, even if not always personally revealing. So, like it or not, my life’s work seems to be to create the Great Anton Songbook, for whatever micro-cosmic reason.

If ‘Glitch Wizard’ is the sound of looking inward, processing, unspooling, rewiring, then ‘Dig The Light’ feels like a counterweight, a way of extending a hand outward. Did you intend for these two albums to be companions in this way, or did you realize the thematic duality only after stepping back from them? And as someone who’s constantly shifting between solo creation and collaboration, does one of these mindsets feel more natural to you?

‘Glitch Wizard’ was finished before the US election and is very “me, me, me” in a way. I did rewrite one song, “Secret Sister Please,” shifting it from a murky/creepy narrative into a plea to the Goddess for wisdom. ‘Dig The Light’ was written after the election and was first called “Dirtworm.” I’d pictured an angry, fear-based album, you know? I wrote and recorded the ‘Dirtworm’ title track and tried to find more ugly and evil within to share, but I was still having the aforementioned mystical experiences. One in particular really knocked me down—in the best way—and I suddenly saw that I needed to make a record that contained love and expressions of openness. ‘Dirtworm’ got the axe and ‘Dig The Light’ started writing itself.

My studio had been growing as well, so there’s a tonal shift from one album to the next. And, to be honest, I grabbed a handful of older songs that fit the feeling of the album. ‘Dogstar’ was recorded in 2007! Anyway, because our world has taken a terrible turn of late, I felt it vital to get Dig The Light out as soon as possible, rather than as the eventual follow-up to ‘Glitch Wizard.’ I don’t mean that my album is going to change the world or save anybody from anything, but it does contain love and light and messages that I find calming. Maybe that will resonate with others. Otherwise, they can glitch and twitch to Donneye’s ‘Glitch Wizard’ guitars!

“I take humor very seriously”

Psychedelic music often walks the tightrope between mysticism and absurdity, between spiritual revelation and cartoonish hallucination. Your music has always embodied both. How do you decide when to lean into the cosmic and when to embrace the ridiculous? Do you think the balance between the two has shifted on these latest albums?

The straight-faced answer is that the cosmic leans into us when it’s the moment for such, maybe. Meanwhile, I ALWAYS embrace the ridiculous!

I take humor very seriously, but I do see these albums as not as whimsical as my work can sometimes seem. I’m no snob, and the dumbest songs in the world will still get my vote if there’s a hot fuzz guitar solo, right? In the end, it’s all the same chewing gum.

Having Barry Melton (of Country Joe & The Fish) on ‘Dig The Light’ feels like threading your music back through a longer psychedelic lineage. How does someone like him—who was there in the thick of it in the late ‘60s—hear what you’re doing now? Did you get a sense of how he perceives the evolution of psychedelia from his generation to yours?

I met Barry through a fellow in London called Psychedelic Mike. Mike is a full-time psychedelic music fiend, but by day, he’s a cop! He’d seen me with the Bevis Frond and had started helping me out with bookings around London. He had Barry Melton coming over for a tour and suggested me for the support slot. Turns out Barry lives 11 miles away from my dad’s house in Sacramento. I popped over to meet him so he could make sure I was alright! We got on easily right away, and I got the gig.

That tour was a blast—I’d do my song ‘Drug Free’ with Barry and band backing me. He’d introduce me every night as an ex-CIA guy who’d been outed by the band. He’d weave this into an intro for my first song and off we’d go. I haven’t seen Barry in many years, since I moved abroad, so I don’t feel I can dare to speak for him regarding his take on anything, but he seemed to enjoy our gigs together, so that’s plenty for me!

The recording session for the song ‘Dogstar’ took place in 2007, I think… the song was released about ten years ago by an Italian tape label, then it came out as a 7-inch last year on Fruits de Mer. It’s funny—but quite fitting—that the song has finally found its moment on an album. “The way the world is going, I’m gonna grab my girl and getaway…” Right? Anyway, about the session: Barry brought a Mesa Boogie amp that the company had made just for him. SOOOOOOOOOOOOO FUCKING LOUD! Like, Woodstock volume. It was amazing. He was amazing.

Your songs often feel less like they were written and more like they emerged—lyrical fragments that collide and reshape themselves over time, melodies that wander into unexpected corners. What’s your process for capturing these ideas before they dissipate? Do you ever feel like you have to chase them down before they escape into the ether?

I do find myself spending less time doing “traditional” sit-down songwriting. Meaning, if something pops to mind, I will grab the guitar or sit at the piano and sketch out chords or a tune, etc. But just as quickly, I’ll send that recording from my phone to my laptop, where I import it into Logic, my recording program. From there, songs take shape quickly, and a final recording is happening at the same time. I recently bought a cassette deck with USB conversion, which I’m using to dig through the hundreds of tapes I found at my dad’s house. There are so many scraps—and complete songs—lurking on these tapes, and I’ve taken a few semi-formed tunes and fleshed them out with new lyrics or a fresh chorus or such. The supply of material seems endless, for better or worse!

You’ve experimented across so many styles… psych-pop, electronic textures, avant-garde songcraft. If you had to reimagine one of your past albums through the lens of what you’ve done with ‘Glitch Wizard’ and ‘Dig The Light,’ which one would you choose, and what would it sound like?

What a curious question! The thing is, whatever elements have shaped these new albums are specific to this moment. I don’t know if I can separate out the sonic components from the songs and from what’s shaping my life right now. Still, I’ve had a look through my catalog of albums, and I think I’d pick ‘King of Missouri,’ which I made with the Bevis Frond. It’s quite straightforward, production-wise. In fact, it was such a clean pop record that I made the very mushroom-y ‘In The Village Of The Apple Sun’ somewhat in response. The latter, fittingly, has recently been reissued on Nick Saloman’s new Blue Matter label. Anyway, I remember being in Bromley, doing the mixing for KoM, and wishing we had even just one more day in the studio to “make things weird.” I still have the hard drive the album was recorded to, but we used a very specific format, and it’d be near impossible to track down the tech needed to remix the album. Not knocking King Mo—I think the way it turned out actually served me well, as there are people—gasp—who don’t always go for my sonic sorcery. For me, the making of that record with Nick and Bevis Frond was as much a thrill as the final result. Tracking the epic ‘Sylvia Something’ live with the band is now something that couldn’t be replicated or recreated, no matter how many effects pedals I might like to show off!

Something about ‘Glitch Wizard’ evokes a kind of folk horror in sound—like a fever dream where English pastoral psychedelia meets the unease of a forgotten reel-to-reel tape found in the woods. Were there any influences, musical or otherwise, that led you toward that eerie, disjointed quality?

The soundtrack to the film Wicker Man is a huge fav of mine, and I spin Trees and Comus from time to time, but honestly, there aren’t many musical influences I can cite as influences on ‘Glitch Wizard,’ besides my teasing about the not-very-folk-horror-at-all Steely Dan! Any folk horror must’ve come from inside my own psyche! I mean, there are certainly “other” influences that played a vital role in shaping ‘Glitch Wizard’… there are spirits that seem to live in the Dark Mystery Temple—I’m convinced of this by now.

With a discography as deep as yours, are there songs from past albums that still feel unresolved—melodies that still haunt you, lyrics that feel like they belong to a different album? If so, do they ever resurface in unexpected ways?

I’ve never made a great leap away from my history of songs. The very first song I ever wrote, at age 13, has been re-recorded and released as a single in Spain. And that song has held up surprisingly well. I perform songs I wrote when I was 20 in my live shows, alongside brand-new tunes. While it’s fair to say some of my music slithers more deeply into a psychedelic style, there is a consistency to the shape of my songs, old or new. I’m a traditionalist, and I love a catchy chorus, you know? Maybe there are differences in subject matter… my youngest songs are all about “girls” and are filled with fitting energies in that regard. I admire the confidence, if not the arrogance, of my earlier days, where I was convinced every song was gonna make me a millionaire! I’m far more… uh, thoughtful now, if that’s the best word.

‘Glitch Wizard’ feels like an album that taps into a deeper spiritual current, albeit one that’s submerged in distortion and fractured electronics. Do you see your music as a form of spiritual practice, or more of an exorcism of personal or collective demons? Can you describe a moment during the making of these albums where you felt that spiritual current coursing through you?

I think that any spiritual current I’m working with is very grounded in the flesh and blood and cardboard boxes of my “real life,” if that makes sense. I’ve mentioned having had a number of mystical experiences during the making of these new albums. These experiences have shown me images of God and have connected me to realms I’d previously not imagined, but ironically or not, these spiritual moments have brought me back into my body and into the small world I live in. I’m a happy cat owner, right? Both the opening title track and the closer, ‘A Pattern Forming,’ attempt to speak to the transformative experiences I’ve had. It’s cute, sometimes, trying to put the incomprehensible into a pop tune!

Amidst all this talk of spirit and God, I can say I’m not a “deeply” spiritual person—or at least not devoutly so. I’m spiritual-curious, maybe. Still, music for me has always been of the soul and psyche, as a maker and as a listener. My younger music was loaded with all manner of personal dark-blurts… I took my personal life and ran it through the Kurt filter. Maybe I wouldn’t speak of exorcism here, though. I’m increasingly careful about not sharing energies that I think could be considered detrimental to others.

If I had to pick one single moment where all the lightbulbs flash forever at once, it’s Dave Gregory’s wah-guitar on the song ‘Off The Hook.’ Transcendent, krauty holiness.

There’s a beautiful tension in your sound between vintage gear and modern production—old analog synths, tape loops, and the like, yet wrapped in a contemporary sense of atmosphere. How do you approach that balance?

I don’t have a specific approach or aesthetic… I like sound/sounds. I love music, even music I don’t like. I like playing noisy instruments, and I like chopping and mangling audio files and then placing them in exact locations. I have a lifetime’s collection of gear, and I’ve been obsessed with analog synths since before there was any other kind. I am, as we all are, wrapped in the atmosphere of this very moment. My synths are old, my laptop is new. I’m all analog, all digital, all the time. Despite my newfound love for the perfect perfectness of ABBA and Steely Dan, my own approach to recording will always taste like the 4-track mind of a basement teen.

Your lyrics are a rich blend of surrealism and sometimes hauntingly personal imagery. In ‘Glitch Wizard,’ you toy with the idea of existence itself as a malfunction. Do you see yourself as a confessional songwriter, or is there an element of performance to your lyrics, where the persona and the personal blur in the pursuit of art?

I think being artistically “confessional” requires a clear and direct line from heart to mouth to listener’s ear. Clear and direct are not rabbits in my hat, man! I must have an auto-subvert switch inside me stuck in the “on” position. Sometimes I’m deeply affected by art and music that just lays it on the line, tells it like it is. If you feel it, you feel it. But I’m often drawn to mystery and layers and confusion and things that don’t quite add up. Too messy to confess—that’s my bumper sticker for the day!

You’ve had the privilege of working with some legendary musicians—Dave Gregory, Andy Metcalfe, Barry Melton, among others. How does collaboration affect your songwriting process? Do you ever find that the presence of another musician disrupts your own creative flow, or do you see it as an opportunity to bring out new facets of your own style?

It’s a little bit chicken and egg. Some songs are written with a certain player in mind, and in those cases, I’m usually sending them what I consider to be a very solid song—and a song that has their own sound and personality in mind. Sometimes it’s a casual “we should do something together sometime…” situation, where the right song comes along after a musical connection is in the works.

I think by this point, especially regarding the people you’ve mentioned, I have a solid sense of which song is right for which player. And if, say, I send a new song to Andy but it’s not connecting with him, we’ll simply drop it and try again with a different song. It just blows my mind that all these heroes from my record collection are helping me make records. I can sometimes take liberties with tracks people send me, but I try to do so in a way that’s still in honor of their contribution. One of the keys for me to working with my heroes is that it raises the bar for my own work. Colin Moulding once sent me some backing vocals beyond the main part we had planned for him to sing. These extra vocals were stunning—very complex, yet as pop-catchy as you could wish for. There are so many musicians who operate on a level I can only dream of, but at least working with these folks gets me past security and into the club!

Klemen Breznikar

Anton Barbeau Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp

Think Like A Key Music Official Website / Facebook / X / Instagram / Bandcamp / YouTube