From The Elastick Band to Max: Revisiting ‘Rodan’ and Its 50th Anniversary

We’re taking a trip down memory lane with David Cortopassi, starting with the wild ride of The Elastick Band and their mind-blowing track ‘Spazz,’ all the way to the psych-jazz of Max and the remarkable release ‘Beyond Rodan.’

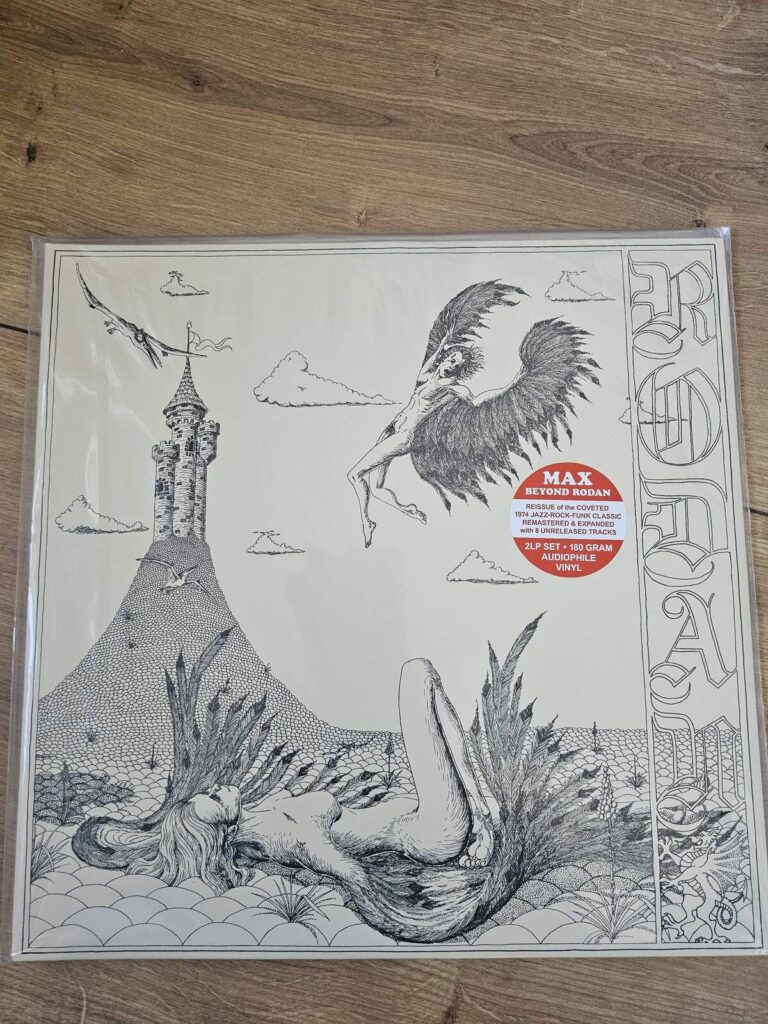

David laughs as he remembers, “I can’t even remember who gave me a copy of the original ‘Rodan’ album. It wasn’t the person who pressed it. But I do remember how shocked I was when I got it!” Despite some confusion over the name, with most people still calling the band ‘Rodan’ instead of Max, things have cleared up over time. ‘Beyond Rodan’ really sets the record straight, showcasing the evolution that brought the band to its true form.

Now, with the 50th-anniversary release of ‘Beyond Rodan,’ which comes with remastered tracks, unreleased photos, and new liner notes, Cortopassi says, “I had to do this. It never felt right to me for 50 years. The ‘Rodan’ album never gave credit where it was due. We didn’t “make it,” but it was a powerhouse of musicians who really deserved recognition—especially considering how much love it still gets today. You just don’t hear music like this anymore.”

“Those that played in MAX were pros.”

It’s wonderful to have you. David, can you take us back to your earliest memories of music—playing the marimba at age five for the USO with your siblings—and describe how that unique start influenced your life?

David Cortopassi: Thanks for having me. My brother and sister played professionally (marimba and accordion) and also performed on USO tours. I wanted to be in the act, and they included me when I was about 5 years old. We performed as The Cortopassi Trio, playing, dancing, and doing pantomime in a variety show called Braiden’s Follies. We were one of about 10 acts that included anything from a magician to comedians, to acrobats, and an all-girl chorus line.

Some of the performances were in top-secret government camps. I can remember getting on a bus with the entire entourage; an MP would pull down the shades so we couldn’t see where we were going. When we arrived, we’d get out inside an airplane hangar or walk through a canvas tunnel into a large Quonset hut, and there would be hundreds of soldiers waiting—literally hanging from rafters, cheering. We’d get on stage, do the show, eat at the commissary with the soldiers, then get back on the bus without ever knowing where we performed. The best acts usually opened or closed the show. We closed… mostly because my sister was gorgeous and all the servicemen went crazy over her. We played together like that until I started high school.

I guess you could say the experience brought out a heightened sense of theatre or theatrics in me. Early on, I was ingrained with the notion: “There’s No Business Like Show Business.”

You’ve mastered such a wide array of instruments—from marimba and vibraphone to various guitars, mandolin, banjo, and piano. What drove you to explore so many instruments?

My sister played marimba, so the instrument was there from the beginning. If you can play that, you can play vibes. From early on, I was listening to an eclectic mix of major artists like Les Paul & Mary Ford, Sinatra, Montovani, Xavier Cugat, Dominic Frontiere, Broadway musicals… whatever. My uncle had a 4-string Vega banjo he lent me, so I learned that on my own. Mandolin is the same fingering. I still didn’t know fingering on a 6-string, so I bought a 4-string tenor guitar I found in a hock shop and tuned it like a tenor banjo. I kept looking for a guitar I could immediately play and saw a Gibson ES-125 at a fine luthier store called Satterlee & Chapin in the San Francisco Tenderloin district. Someone had previously modified it to be a 5-string banjo. I asked if they could shave the neck and turn it into an 8-string guitar (similar to a 12-string), only tuned like a tenor guitar in the key of C. I still have that guitar today.

While in high school, I played in the orchestra and the only available instrument they had was a bass violin. So I played that for 4 years (mostly classical music), but also in the dance band (stuff like Duke Ellington and Glenn Miller). I also tried clarinet (Gus Bivona had a hit called ‘So Rare’ out at the time and I wanted to play it), but the instrument was too foreign to me and the embouchure was giving me buckteeth. I also tried flute, but it just frustrated me. I related to marimba/keyboards/synthesizers/piano much more easily, so I stuck with that.

Back in those days, how involved were you with the local clubs and bands? What was it like being part of that early scene?

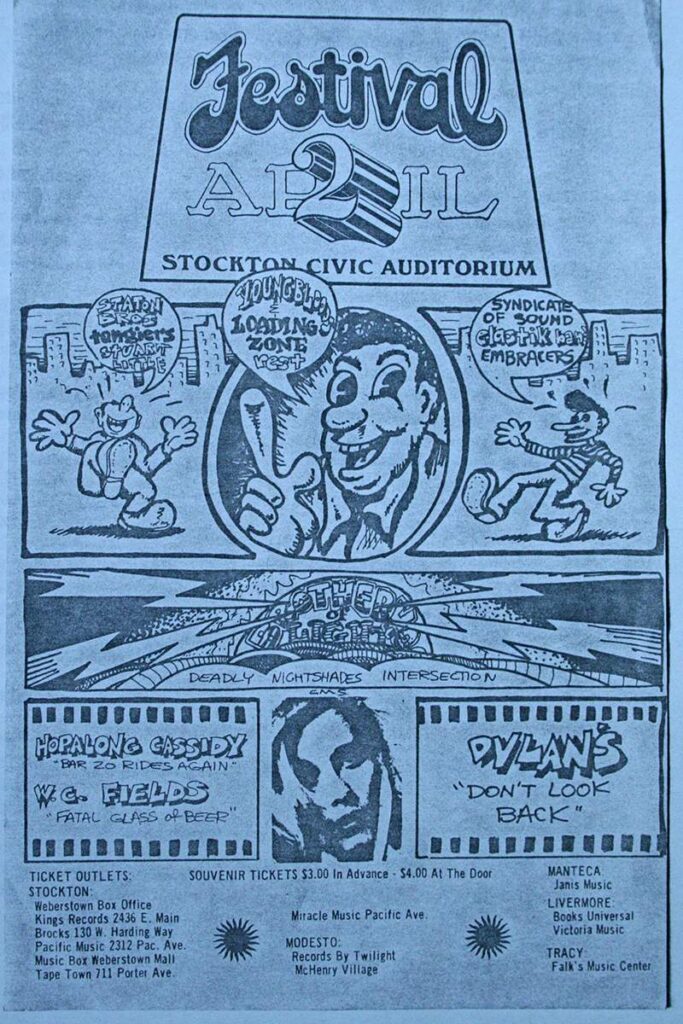

Frankly, at the time I didn’t really realize I was a part of the psychedelic/hippie movement when it was happening. Never really thought about it. I went into the Haight-Ashbury area all the time just to hang out, but I don’t think anyone who did so thought it was or would become a “thing.” I played anywhere I could get a gig and auditioned at any club looking for bands. Played The Matrix, The Fillmore, The Orphanage, The Hello Doll… wherever. Bands started, ended, and changed all the time. Truth be known, it didn’t occur to me that bands like Country Joe and the Fish, The Youngbloods, or Moby Grape were doing or attempting anything different than what The Elastik Band was trying to do. And they were not all that well known yet at the time. I didn’t even know that Woodstock was happening—or going to happen—until it happened. Wish I had.

In the early ‘60s, garage bands were all the rage. What was it like forming the Soul Survivors in high school, playing covers for free gigs and private parties?

The Soul Survivors was definitely a learning experience. We barely had any equipment. We played songs like ‘Gloria’ (Van Morrison), ‘House of the Rising Sun’ (Animals) on cheap instruments using small amps with lousy microphones. We even used a 6-string guitar as a bass by tuning it an octave lower using the thickest strings available. We mostly rehearsed in the garage. If a friend had a birthday party, we’d play for free. My high school had a “Battle of the Bands” event in the gymnasium. About 10 bands participated—many bands from other high schools also competed. Most other bands had slick Fender Bassman or Bandmaster amps that looked very cool with their “red lights” beaming. We didn’t. We had junk. We sounded okay but lost big time.

I think the highlight of that band was playing at a YMCA dance in our senior year. To try to make Soul Survivors more acceptable to the in-crowd, we spent $50 on lumber and built a high-rise platform for the drummer that we put on top of a raised stage. We hid our ugly amps under it behind a curtain. The dance was a great success and everyone loved us. Yep… those were the days.

What led to the formation of This Side Up? You released ‘Lose Yourself’ / ‘Turn Your Head’ (Century Records) with this band. What do you remember about forming that band and those early recording sessions? How did the creative process evolve?

After graduating high school, 2 band members changed, as did the name—from Soul Survivors to This Side Up. I tapped my cousin to play piano and saxophone and had written a few songs. By now, I had become serious about only writing original compositions.

I had known George Dipaola for several years when he decided to rent a space and office in Belmont, California, to recruit musical talent. He didn’t really know a lot about the music industry but had tons of enthusiasm, energy, and more intestinal fortitude than 10 people.

George let me work there a bit and record ideas floating in my head. Some were ridiculous and some were worth attention. Eventually, This Side Up also began to rehearse, practice, and record demos on very meager equipment George provided in what you simply could call a “room.” It gave us a chance to pick and choose.

What can you recall about the intimate, almost guerrilla-style recording sessions with George Dipaola and Brian Gardner in his living room, especially knowing that only 100 pressings were made?

It wasn’t very long before George Dipaola (producer) introduced me to Scott Williams (lead guitar) and Brian Gardner (engineer). Brian was fairly new to California and was looking to somehow get a foothold in the recording industry. He owned a pretty good 2-track tape deck along with a few excellent microphones that he used to record us in the living room of his home. This was bare-bones recording. Brian used just about every room in the house for separation. That took a while to get right. He didn’t have much in the way of other equipment like equalizers or effects, so for echo/reverb on vocals, he used a microphone in his tile bathroom. I think it took 2 days to record that record—one for Side A and another for Side B.

George unfortunately passed away while still relatively young. Brian Gardner went on to become a world-famous mastering engineer who has been nominated eight times for Grammy Album of the Year.

During the San Francisco psychedelic era, when you caught the attention of Hank Donig, how did his advice and the pressure to change your band’s identity lead to the birth of The Elastik Band?

I’ve got to give Hank Donig credit for naming The Elastik Band. The name nailed the idea that we could emulate many types of music coming out during that era. Plus, Hank was your quintessential salesman. He could sell anything to anyone who didn’t think they needed anything. I really loved working with that guy. Never met anyone like him and never will again. Talk about energetic! We laughed a lot, brainstormed together, and even got emotional at times until something worked. He had more going on than you could imagine and did it all. A very talented man, he owned several nightclubs, lived on the edge, and basically became a band member. Hank was truly a producer. But you never thought he was a producer even while producing… the man made you produce. I miss that guy. I learned so much from him—as I did from Lamont Dozier (only different) many years later.

What was the philosophy behind that name?

We decided on The Elastik Band because the versatility of the band demanded it. Personally, I consider myself a composer rather than a performer. I feel I can write just about any style of music—although I most likely can’t, but I still think I can. I perceive each of my albums as being very different in genre. Hopefully that comes across to the listener.

Who were the other members, where did you all rehearse, and what was the atmosphere like during those early gigs and recording sessions?

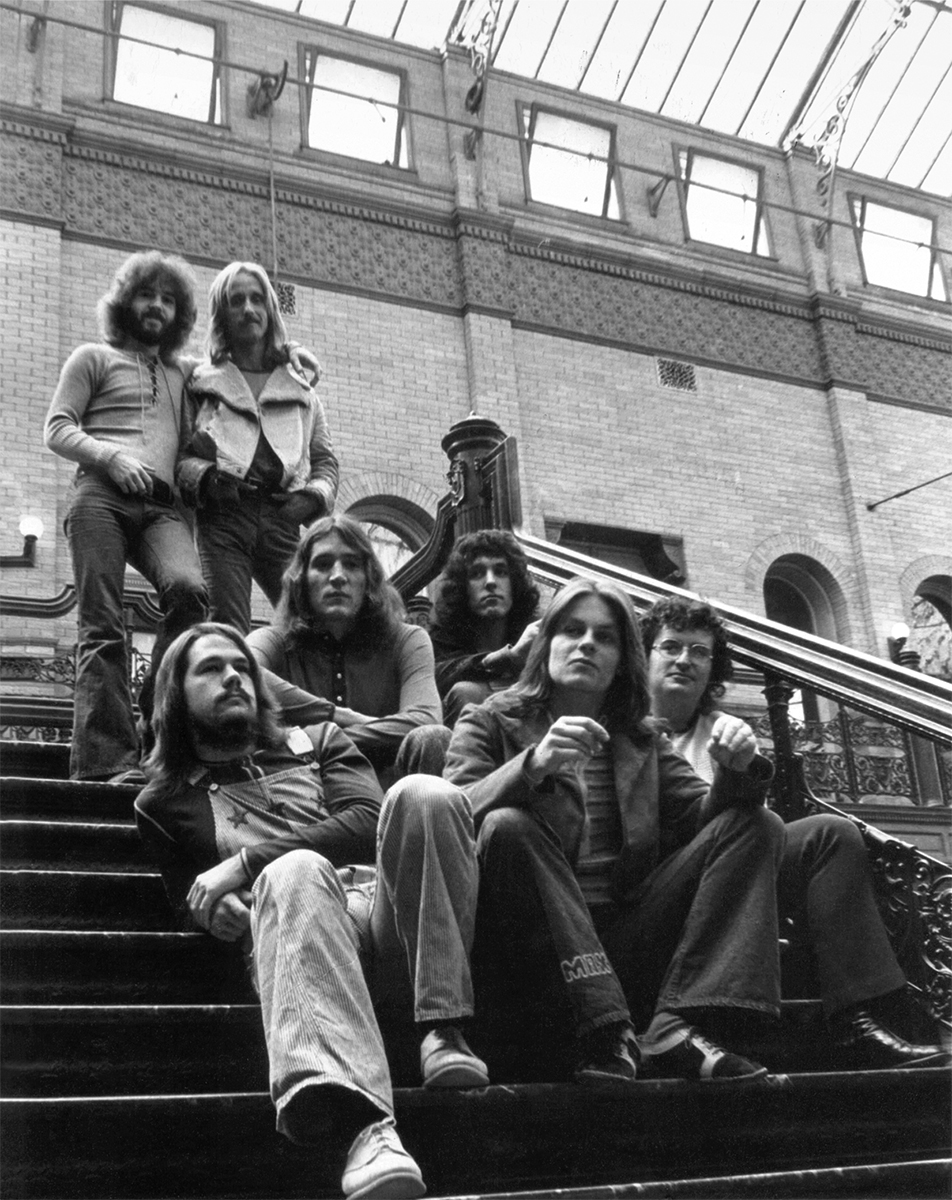

Members of The Elastik Band included me, my cousin Russell Kerger (saxophone, electric piano, background vocals), Rusty Kierig (bass guitar, background vocals), Vince Silvera (vocals, drums—who was with me since Soul Survivors), and Scott Williams (vocals, lead and bass guitar). David Sturgen (bass guitar) and Rebecca Tieson (vocals, flute) were also brief members of the band.

Mostly, we rehearsed in my parent’s garage while trying to avoid neighbors from complaining about being too loud. Gigs were fun, and we often used gigs to try out new songs.

Once, one of my bands (I think MAX) rehearsed at Studio Instrument Rentals in Hollywood. As I remember, one of our roadies for that band worked there and got a complimentary padded cell (ha ha) for free. It was a hassle because it was right on Hollywood Blvd., and getting in and out was such a traffic jam.

Can you describe the excitement and challenges of recording with Donig and Fred Cohn at Action Records, especially for tracks like “Got A Better Reason” and “Mixed Emotions”?

Recording sessions usually started late afternoon and lasted until the following morning. Mixdowns and mastering often took several hands and multiple attempts to complete. These early recordings at Action Records were done in a well-constructed studio with excellent sound reinforcement that enabled separation of instruments, vocals, etc. The hard part was we were limited to a 4-track deck. If we needed more tracks, we had to mix some tracks down to an open track to free up another track… thus losing future control over that mixed track. To extend that ability, we took advantage of recording another part during mixing down to a 2-track stereo master. There’s always a way. It’s always a challenge.

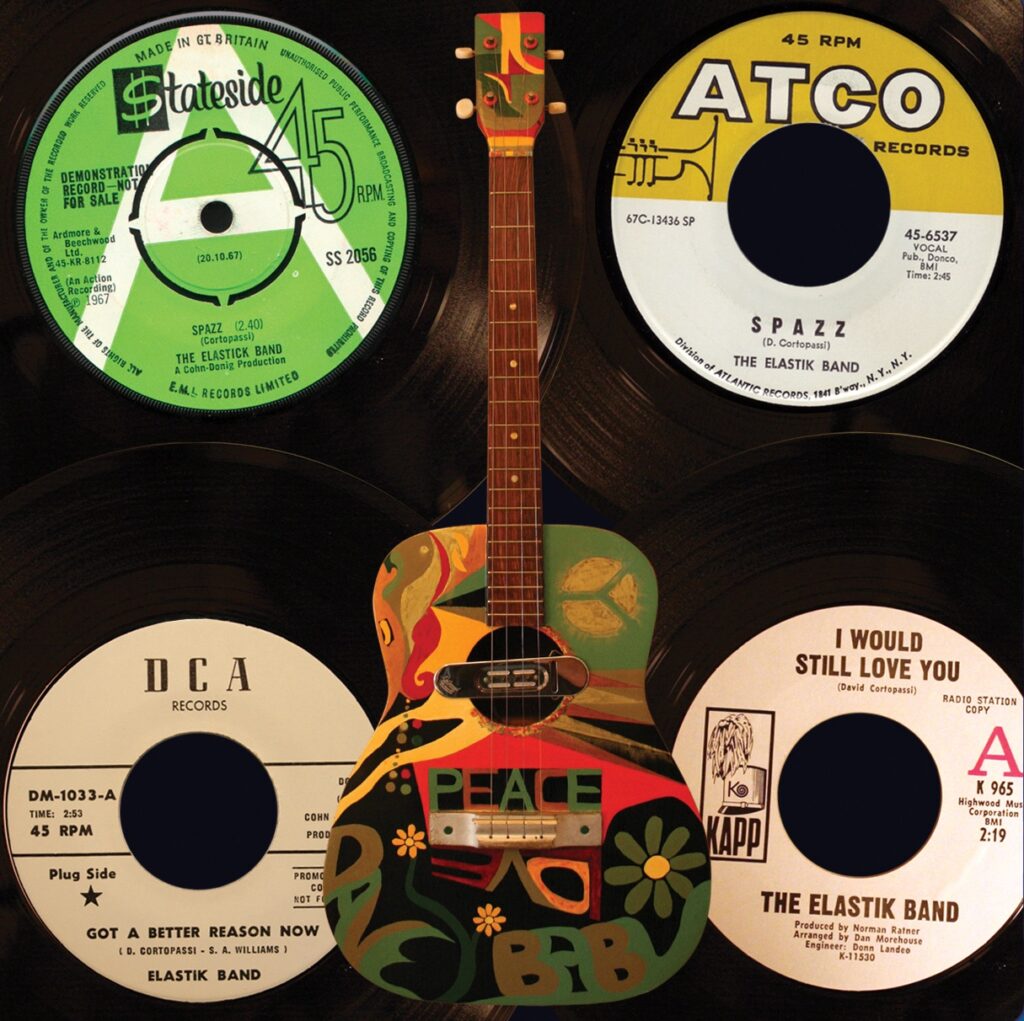

Action Records recorded ‘Got A Better Reason Now’ and ‘Mixed Emotions,’ and released a 45 of them in 1967 on DCA Records. I think the issue with that limited release was the lack of promotion.

“The record got banned in Europe.”

‘SPAZZ’ became a cult classic and a lightning rod for controversy, even being banned in Europe. What were the circumstances around its creation?

Fred Cohn, who engineered ‘SPAZZ’ at Action Records, brought an acetate with him to New York in an effort to shop the cut to a few of the major record companies. In a stroke of luck, he happened to meet Jerry Wexler in the elevator of Atlantic Records (Wexler produced many of the biggest acts at the time, like Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, Bob Dylan, Booker T. & the M.G.’s). Wexler took it on the spot. (When does that ever happen?)

Thinking ‘SPAZZ’ would launch the band, it was released on ATCO, a subsidiary of Atlantic. The song soon aired on a radio station in San Francisco (coincidentally, the only time I ever heard it played on the radio). It got a HUGE response. So huge, the station thought the band staged a mass call-in requesting they play it again… we hadn’t. We were just kids without a clue about PR or promotion. Though the record got a terrific response at radio stations, DJs deemed it to be a publicity scam and refused to play it.

Next, while ATCO released the record on EMI’s Stateside label, Hank Donig was simultaneously setting up a tour in Europe to help promote it. It was then that we heard about some DJ in Australia pulling ‘SPAZZ’ off the air and apologizing for having played it.

Ultimately, the record got banned in Europe. A caption in two separate trade magazines read, “SICK RECORD BANNED.” EMI withdrew the release while one of their spokespeople announced they didn’t realize the meanings of some of the “Americanisms.” Hank canceled the tour.

Evidently, people said they’d throw rocks at us when we got off the plane. As an aside, it was years later that a fan in Australia, who had actually recorded ‘SPAZZ’ while it aired live, gave my son a copy of it. That cut is included on The Elastik Band CD that I released in 2007.

Truth is, as a teenager living in California during the mid-sixties, there was always pressure to get turned on or try some kind of hallucinogen. Heck, even John Lennon’s lyric “I’d love to turn you on” from the ‘Sgt. Pepper’ album was released that same year. Though drugs were prevalent, I didn’t do marijuana or psychedelics. Didn’t even smoke cigarettes. But it was difficult to avoid, and it made me feel like an outsider. I became more rebellious about it. So while everyone seemed to be dropping acid or eating magic mushrooms, I wrote ‘SPAZZ’ as an anti-drug statement. I never thought it would be interpreted as a put-down about people with disabilities. But in retrospect, I doubt anyone other than me knew what it was supposed to be about.

How did you end up getting signed to ATCO for ‘SPAZZ,’ and what followed after that? The later releases were on DCA and Kapp—how did those deals come about?

Action Records wasn’t exactly a record company; rather, it was a recording studio trying to stretch out or obtain distribution for what they recorded. Remember, it was the heyday of the 60s in San Francisco. In my opinion, even record labels were kind of in limbo—continually adjusting to the San Francisco Music Movement.

I never actually signed with ATCO. Action made a distribution deal with them, but as it turned out, the end result didn’t come to fruition. After ‘SPAZZ,’ options were disappearing, so I moved the band to Los Angeles, where there were at least 100 record labels.

After the notoriety of ‘SPAZZ,’ your move from San Francisco to Los Angeles and the signing of a 7-year contract with UNI marked a dramatic shift.

It certainly did! Moving to LA was definitely a BIG shift. Within a 10-mile radius, you had companies like Capitol, Columbia, A&M, Warner, Elektra, UNI, PolyGram, and tons of smaller labels like Parrot and Double Shot. Scott Williams and I walked up and down both Sunset and Hollywood Boulevards with our guitar cases and just strolled directly into all of them. Most were welcoming, except for Columbia Records (Mitch Miller, head of A&R, didn’t like Rock ‘n’ Roll—he even passed on The Beatles). If they didn’t know you, they’d audition you on the spot. That’s how I got signed with UNI.

When UNI rebranded your band as Dangerfield and shifted your musical direction, what impact did that have on your creative freedom and the overall identity of your music? How did the introduction of orchestras, arrangers, and a new managerial team under Joey Fischer and Norman Ratner affect the band’s spirit?

Universal believed in the Elastik Band, but everything changed. It’s a major conglomerate that does what it wants. UNI hired orchestras, arrangers, gave the band a new manager (Joey Fischer), and a staff producer (Norman Ratner). None of this complemented the band’s nature, musical style, or direction. We had very little to say. All of a sudden, we had a full orchestra, they hired an arranger for it, and they had us doing music we didn’t write… they even had me arrange a Jimmy Webb song (Tunesmith) using a 3-girl chorus singing in the background. We weren’t us anymore.

Believe me… I could go on about that experience. But it wasn’t all bad. KAPP, a division of Universal Records, did send us on a shopping spree at Guitar Center in Hollywood (THAT was cool!). We pretty much got whatever we wanted—a vibraphone, guitars, bass, complete drum set, saxophone, Wurlitzer Electric Piano. At the time, they spent at least 10 grand. They also gave us unlimited recording time at Sunset Studios with Donn Landee engineering (later worked with Doobie Brothers, Van Halen) and released three 45s.

After taking out full-page spreads in Billboard magazine, UNI decided to change the band’s name to Dangerfield. Over the course of 2 years, the band recorded 2 full LPs worth of music… most of which was never released. Basically, the band was then “shelved” until I requested to be released from their 7-year contract. Universal said “NO” while threatening to take the band’s equipment away from us. After much negotiation, UNI finally released us when I said the band would report non-payment of studio recording fees required by the Musicians Union. The experience was a difficult one in many ways. So much so that 3 of the band members thought it was time to pursue other careers.

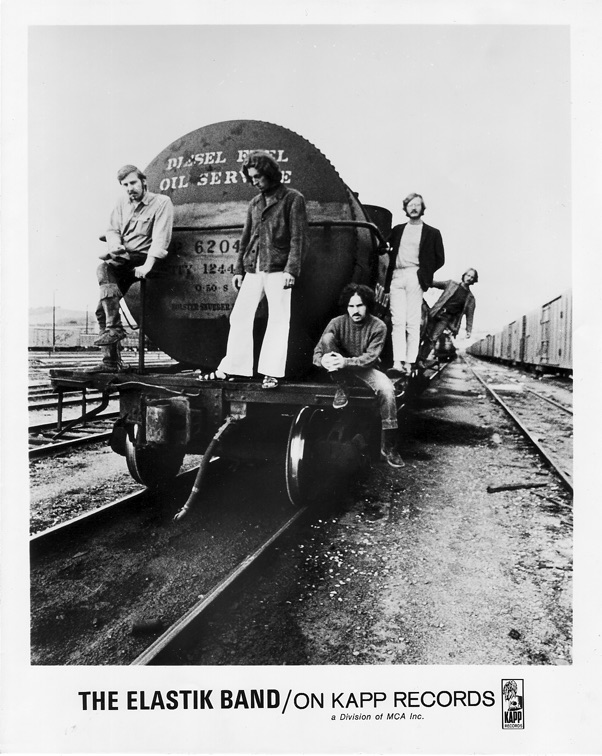

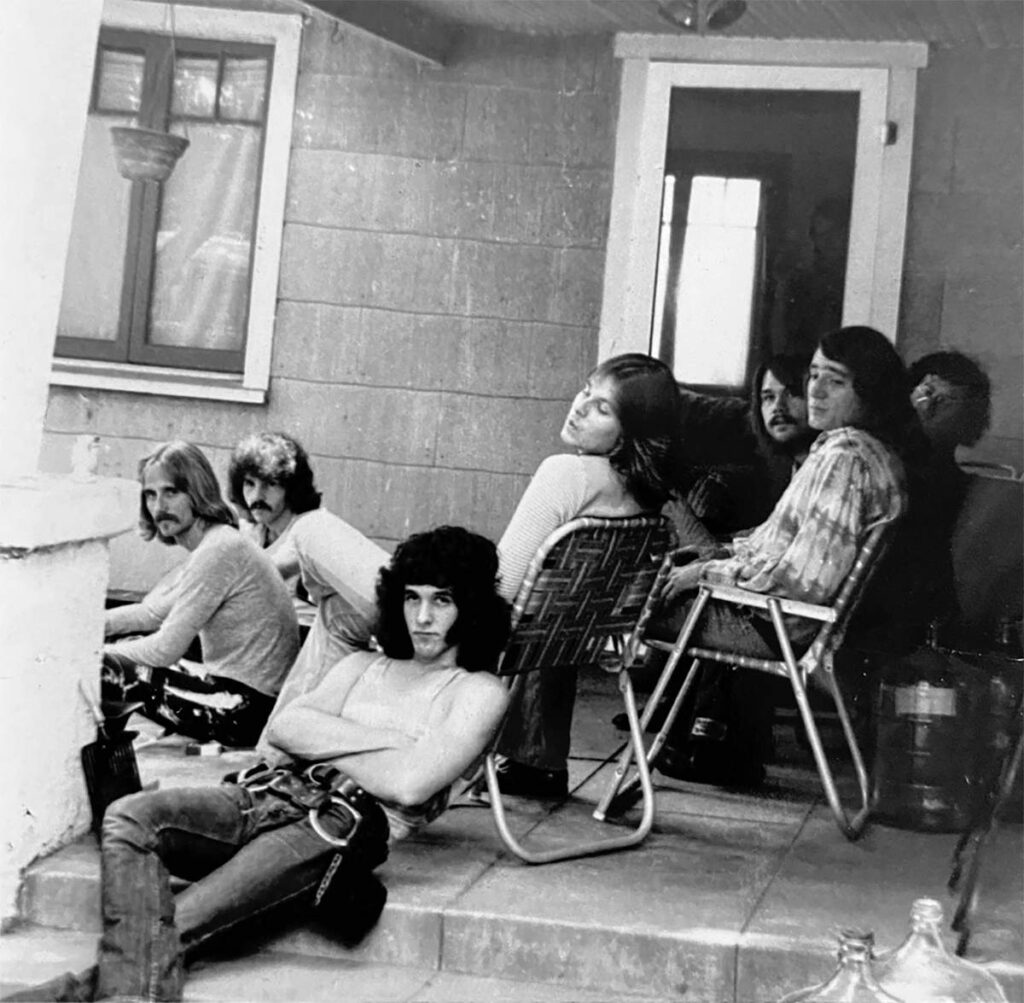

What led to the formation of MAX, and who were the members? What was the original concept behind the band?

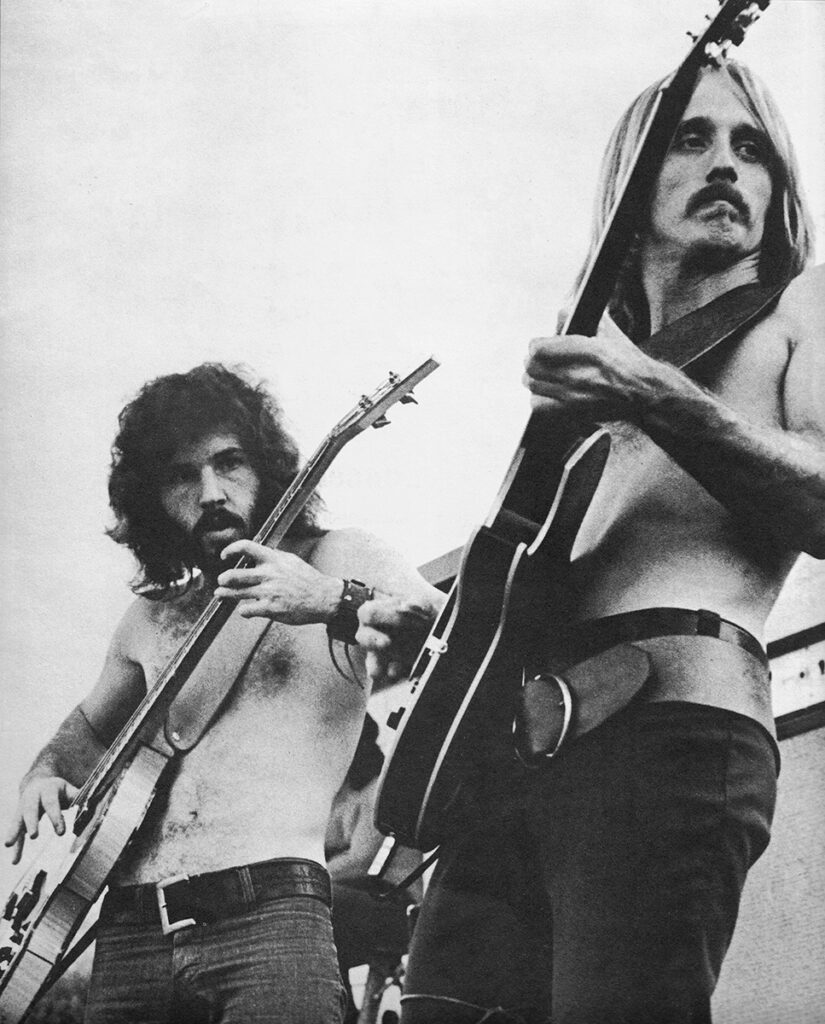

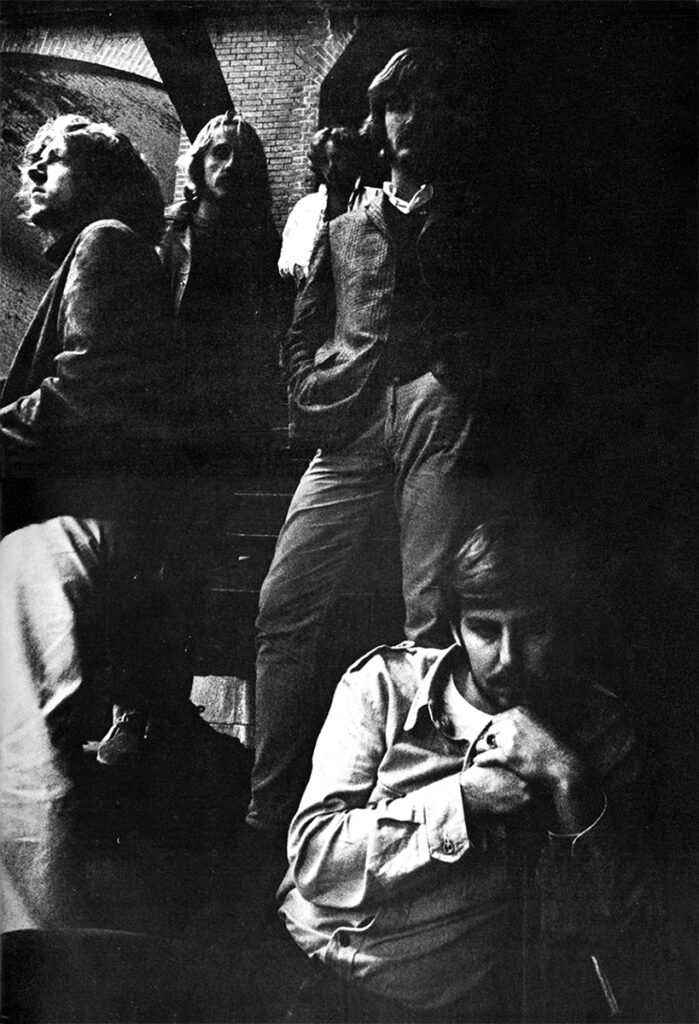

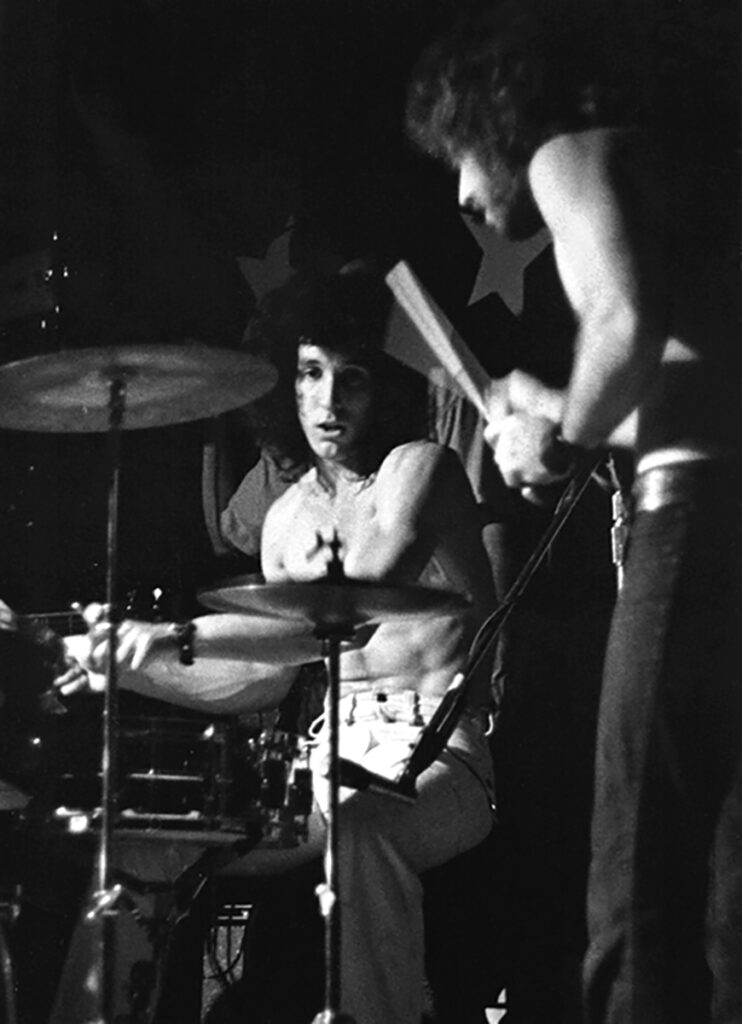

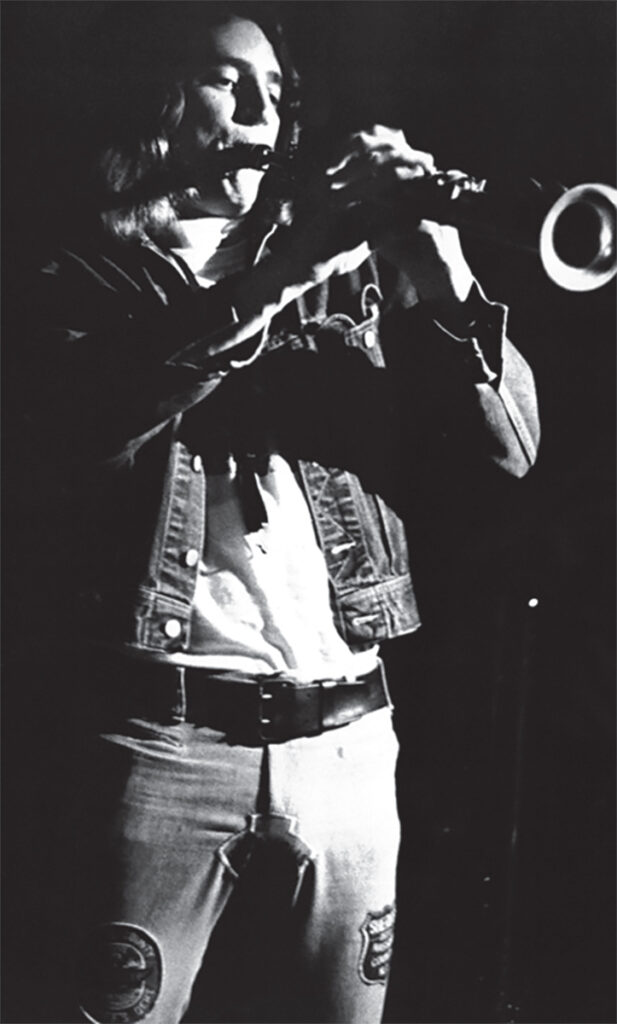

After the Elastik Band dissolved, Scott Williams and I went on to form a new seven-piece rock/fusion band—this time with a brass section. I wanted the ability to better fulfill some of my writing and arranging skills. We placed an ad in The Hollywood Reporter and lined up four exceptional musicians: Scott Page, Steve Mann, Stephen Coyne, and John Leys. Together, they played over 20 different instruments—not just brass, but also wind and reed instruments. We played rock & hard rock but infused it with jazz and a little bit of funk. The combinations at hand were somewhat endless.

The story behind MAX’s album ‘RODAN’ is shrouded in mystery—a bootleg pressing of only 200 copies, incorrect liner notes, and an air of unauthorized release. How did you come to learn about this, and what does that chapter of your career represent for you?

I can’t even recall who gave me a copy of the original ‘Rodan’ album. It wasn’t the person who pressed it. What I do recall is how shocked I was to get it!

Much has been corrected and ‘Beyond Rodan’ documents it, yet everyone still thinks the band name was ‘Rodan’ rather than MAX.

With the 50th-anniversary release of ‘Beyond Rodan,’ featuring a remastered version, eight additional tracks, and unreleased photos and liner notes, what was the experience like revisiting and re-contextualizing that pivotal period of your career?

It was something I had to do. Something that just didn’t sit well with me for, well, 50 years. I needed to make it right. Not just for me, but for the band members. They all believed in MAX and stuck with it through thick and thin. The Rodan album didn’t even give credit to those who were a part of it. So no… we really didn’t “make it.” But it was a powerhouse of extraordinary musicians that achieved something rare and deserved to be acknowledged… especially when you consider the esteem and following it’s garnered today and after the fact. You don’t hear this kind of music today.

Can you delve into the eight previously unreleased tracks on Beyond Rodan? Can you give us some insight into those recordings?

Over the years, I’ve always made it a practice to maintain, keep, and store all of my recordings. Obviously, I had no input into the original ‘Rodan’ album or the selection of songs for that album. Regarding the previously unreleased tracks on ‘Beyond Rodan,’ some were recorded over the same period, and some were not. There were a few changes in band members between recordings, and different recording studios were used depending on where the band was living or traveling. Whenever you record, the quality between different studios and the ability of the respective engineers have their own distinct sound. That said, my favorite cuts are those recorded at Sound City and Pacific Recorders. Both studios delivered that same “classic” touch that wakes you up and glistens. That’s the best I can say it. It’s not only the studio, though; it’s the engineer, his perception of the band, and his ears. You might replicate the studio, but you can’t deny the human element. David Grover’s talent for remastering all the songs at Mystic Mountain Sound was extremely beneficial in matching all songs so they closely reflect the album cuts as being recorded in a single studio.

MAX had an incredible lineup of musicians, some of whom played with Pink Floyd, Toto, Jeff Beck, and Blood, Sweat & Tears. What was the chemistry like within the band?

To be a part of MAX was always amazing. I think (hope) it was fulfilling to each of us before, during, and after we played. Everybody had a chance to embellish, do solos, stand out, and display their abilities. In my experience, musicians usually respect their peers and are even in awe of anyone that deserves to be on their level, no matter what their background. Those that played in MAX were pros. Even those that had little exposure to playing with “headliners” were pros. That is what it takes to be in a really good band. But just as in any other career or profession, musicians have their own desire to stretch out and do music other than what the band does. There were some kinks here and there with MAX, but you work them out, move on, change direction, or find someone or some band that has the same chemistry or motivation.

What were some of the most memorable concerts MAX played? Any gigs that stand out as particularly wild or unexpected?

All of the above. There are a few incidents that come to mind, but there’s one I’ll never forget. I was playing a solo on vibraphone. At one point, one of our roadies (Steve Lehman) would hand me 4 fire mallets (his dad was a metal worker and made them for me). I’d play for a minute or so with them, then set off a couple of fountain-type fireworks taped to each side of the vibraphone that sprayed upwards 6 or 8 feet for about 30 seconds. But there was one time the back of Steve’s hair somehow caught on fire and he didn’t know it. He just kept smiling while watching until a couple of band members saw it and rushed over and whacked his head to put it out. He wasn’t hurt. Years later, even Lehman still laughs about it.

Did the band have management, or were you handling things yourselves?

For a short time, Hank Doing managed the band while we were gigging in San Francisco. When in LA, concert promoter David Forrest booked MAX through CMA (now ICM Partners). MAX, as a group, never signed any agreement with any entity. We did get a couple of offers, though. One came from Wooden Nickel Records, and another from Lamont Dozier through Greif-Garris Management. Just couldn’t agree on the terms.

How long was MAX active, and what led to its end?

Although MAX was active from 1970 to 1974, players did change during that timeframe for diverse reasons. For example, early on, our original trombonist was more interested in pursuing a career aligned closer with Big Band and became very successful in that genre. Decisions like that happened. It’s hard work, so you better love it and be devoted to a common goal. But after four years without a “deal” or substantial income and you’re hitting 30, you need to consider the idea it might not happen. You need to think of your future – like owning a home, medical insurance for your wife and kids, etc. Maybe using your college degree to get a steady job and create enough wealth to retire becomes a good idea.

Many members of MAX came to that decision. Holding any band together (and I’ve had several) comes down to these real-life realities. After that, if you don’t make it, music becomes a hobby.

Reflecting on the live performances with MAX, what were some of the wildest or most memorable gigs you played? Were there any shows that particularly encapsulated the band’s spirit or the era’s experimental energy?

Good question. It’s been 50 years, so I’ve had time to reflect on what I miss or enjoyed the most. Steve Coyne (trumpet) actually kept a log of all the gigs we did while he was with us. In reviewing it, I think what meant the most to me aren’t necessarily the larger events like opening for Tower Of Power at the Fox Theatres or Manfred Mann, Malo, or Quicksilver Messenger Service at the Whiskey-A-Go-Go. My fondest memories are of many of the clubs we played where we brought the house down. The best one was a great hole-in-the-wall called The Buccaneer in Manhattan Beach. We had several weeks there as the house band, and the place was absolutely jammed every night. It was a small venue solely for entertaining the clientele. People went crazy over the band. You could barely move in the club. It was so successful that the waitresses couldn’t get to the customers… meaning they couldn’t serve anyone. No sales, no tips. After about three weeks straight of this madness, the club realized they were losing money. So they fired us. True story.

After MAX, you teamed up with Scott Williams as Free & Easy and even toured with Mitzi Gaynor. How did the dynamics of performing as a duo compare to your earlier, larger band experiences, and what insights did you gain from touring with such an established act?

I was performing in nightclubs with Scott as a duo called “Free & Easy.” While playing at the Portofino in Redondo Beach, Mitzi and her husband Jack Bean (also her agent) saw us and asked us to join the Mitzi Gaynor Show. Both Scott and I were very excited. We did two tours with the show, traveling throughout the USA and Canada.

For myself, having an early background performing in shows similar to what Mitzi did, I felt like I was in my element. I knew what it was about and what to expect. And in answer to your question, when you think about it, there was still a band… a bigger band – only it was in the orchestra pit. They were backing Scott and me. We would play and sing on stage while Mitzi ran off to change her gowns for the next segment. I was used to the proscenium arch, being backstage with all the performers, and having your own dressing room. We were a part of a “troupe” in a bigger show.

Mitzi provided just about everything. Flights, accommodations, rehearsal halls, bus & limo transportation, etc., were all arranged for us. She was a star. I met stars like Bing Crosby, Robert Goulet, Dom DeLuise, and others. Once a week, after the performance, she’d rent out an entire restaurant and take her entire entourage there for a great dinner. It was a lot of fun – just different.

In the mid-1970s to the 1980s, you ventured into different musical experiments with bands like Rage, Fourplay, and The Thuzz. What prompted these shifts, and how did grouping musicians by musical style help you explore new artistic territories?

I was concentrating on a series of diversified recording sessions. Essentially, three band genres materialized by specifically grouping musicians according to the music direction/style for which I was writing. There were a lot of musician friends to choose from, but everyone I knew could do just about any genre I needed. I started thinking about using instruments that were available that I had not really considered using before, like the English horn, recorders, or synthesizers, for example. With some of the songs, a characterization or theatrical approach was assumed for the vocal.

Several of these compositions were co-written with the musicians used on the recordings. I called them RAGE (Top 40 Rock ‘N Roll), FOURPLAY (Underground Rock), and THE THUZ (Independent/Alternative). A total of 18 songs were recorded – some at a makeshift studio at Warner Brothers and some in my own studio. I consider some cuts to be demo quality, but others could be used as masters.

Oddly enough, the genres can more or less be identified by song title. For example, ‘Open Heart Surgery’ or ‘Itzo Skitzo’ (The Thuzz) as opposed to ‘Lowball’ and ‘Mustang Ranch’ (Fourplay). I later re-recorded two songs that came from this: Cool As A Conscience Can Be and Love And Hate. Both were included on my Embrace Destiny CD.

What motivated you to take control of your music production and distribution, and how is running your own label like?

Frustration was the motivation. I didn’t have an outlet for the new music I continued to write, so I started Digital Cellars in 1998 as a vehicle to make the effort worthwhile. I hired a music promoter, PJ Birosik (Patti Jean – RIP) to advise me. PJ was mostly into New Age/Ambient music, and my first release was Pharaoh of Mars. POM matched that genre. So, I learned a bit from her and just dove into the deep end of the pool.

Pharaoh of Mars was created over several months from a few piano solos I would use to warm up my fingers or relax with when I was alone. I wrote more pieces similar to those selections that are on the album, but they weren’t quite as inspiring or peaceful. I thought ensuring the album would be calming or soothing was more important than fear of intergalactic aliens. It seemed to work. I’ve gotten a lot of nice compliments and reviews of that album. People have even written to me about it.

Running your own label isn’t fun. It can be a creative endeavor, but I end up spending less time on composing. I’ve never really enjoyed the business side of the music industry. It’s not something to which I aspire. I do it out of necessity. If a decent record label became interested in taking over the business end of things, I’d be all ears.

What about ‘The Silicon Jungle’ (2000)? The title alone sounds intriguing.

I guess the closest overall theme for ‘The Silicon Jungle’ CD would be World Beat. People have used words like tribal, intoxicating, melodic, provocative, and captivating to describe it. To me, it’s the most thematic or cinematic work I’ve ever done. In summary, I’d say it’s more or less a “protest concept album” about resisting automation and the elimination of the human/animal element. (WHEW… does that sound stupid or what?) – Sorry about that. It’s primarily an instrumental release with only two vocal songs meant to be bookends encompassing the idea—those being ‘The Silicon Jungle’ at the beginning and ‘Rio de Janeiro’ at the end.

And then there’s ‘Embrace Destiny’. What was the concept behind that album?

It’s a slice of life that kind of expresses what people experience at one time or another. Things you reminisce about, lost loves, compassion, mistakes, dreams that don’t come true, hardship, infatuation, hope. Musically, it’s a blend of what I consider sophisticated songs that someone like Michael Bublé or Harry Connick Jr. could be singing rather than I. It’s my best work. When I first released it, I tried to get it to Tony Bennett without any luck.

Is there any unreleased material?

Yep! There’s an entire album’s worth of Dangerfield that was never released when I was with Universal Records. I have a CD called ‘Rock In The Middle Of The Road’ that I haven’t been able to get to. There’s an educational CD explaining the impact of music in film that’s ready, titled ‘Listening To The Movies for Children & Adults Who Act Like Children’… Haven’t been able to get to that either.

What currently occupies your life?

When not busy with the new release of ‘Beyond Rodan,’ my wife and our seven grandchildren pretty much take up my attention.

Thank you for taking your time. The last word is yours.

Just a BIG THANK YOU for the interview and giving me a chance to get the word out about MAX and ‘Beyond Rodan’!

Klemen Breznikar

Special thanks to Josh Cortopassi.

Digital Cellars Website