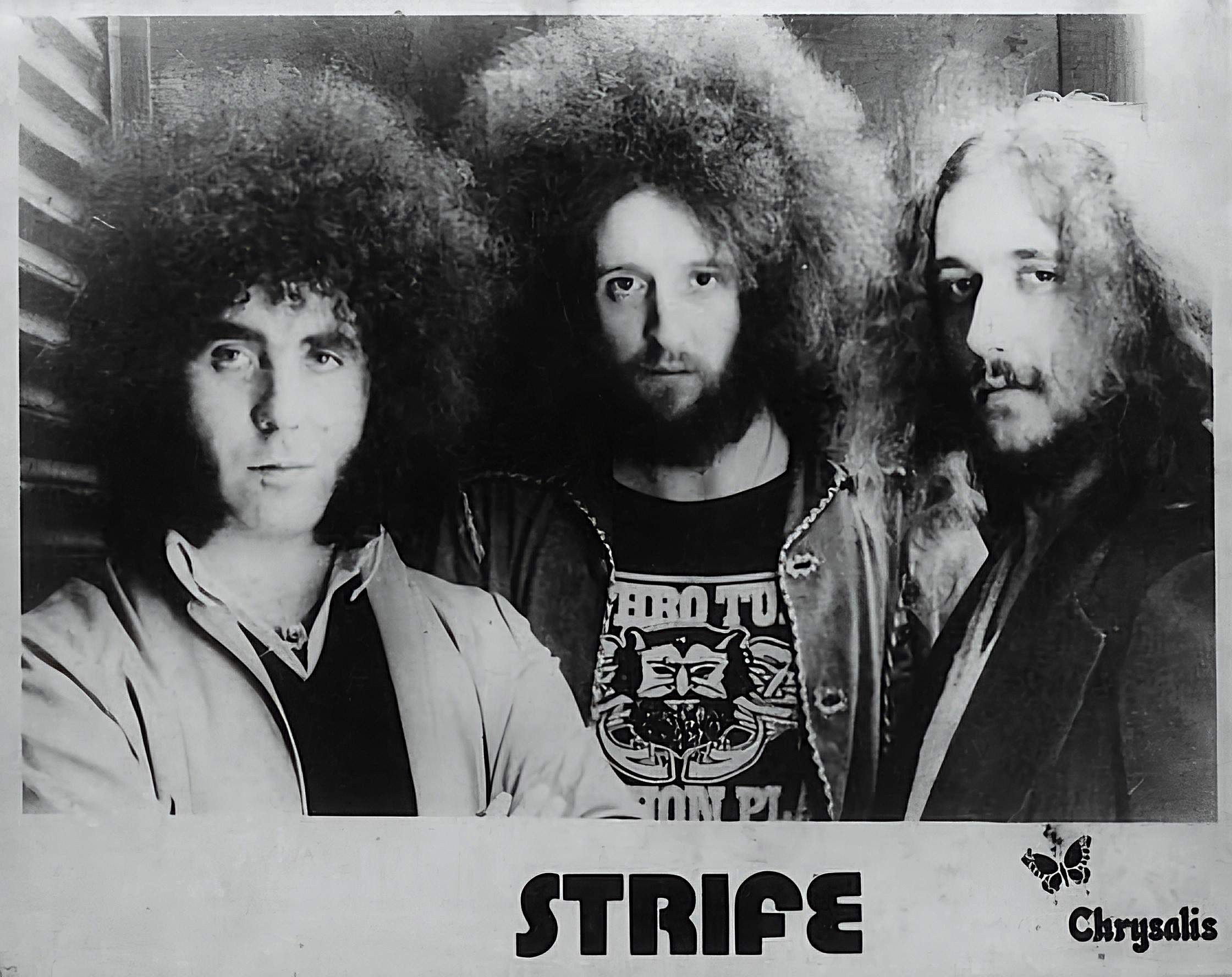

John Reid Talks Strife: 70s Heavy Rock and the Chaos Behind It

Strife? Proper rock ‘n’ roll. Started in ’69, all about the music, no bullshit.

Gordon Rowley nearly gets fried onstage by an electric shock and they just keep playing. Not many bands could do that. John Reid, ex-The Klubbs, joins in ’71, and they start making noise. ‘Rush’ drops in ’75—loud, and bloody brilliant. Played with The Baker Gurvitz Army, at the Cavern Club, all the right places. Even turned down a deal with the William Morris Agency—they didn’t need handouts. Chrysalis? They wouldn’t back ’em after ‘Rush,’ so Strife put out ‘School’ on their own label. Independent as hell. By ’79, after ‘Back to Thunder,’ it was over. Punk and disco took over. But Strife had something no one could take: the balls to say “fuck you” to the whole lot. And that’s what makes ’em unforgettable.

“We must have played around 250 nights a year”

How did you first get interested in music, and what were some of the early influences that sparked your interest?

John Reid: Obviously, living on Merseyside as a young teenager, it was impossible not to be aware of the amount of music that was being created by the Beatles and lots of other “beat groups,” as they were called. I had always liked listening to music and singing, so the next step, at about 15 years old, was to learn how to play the guitar and try and join a group.

My early influences were the bands that had more of a rock edge, like the Stones, The Pretty Things, and The Who, along with some of the American blues and rock legends like Howlin’ Wolf, Chuck Berry, and Bo Diddley, who—with those infectious beats—really inspired me to try and create riffs and rhythms.

Would you like to share about your upbringing? Where did you grow up, and what was daily life like during your teenage years?

Born Christmas Day, 1948, in downtown Birkenhead. Lived in a small three-bedroom terraced back-to-back house—no inside toilet, no heating, just a coal fire in the living room—with one older sister, four younger brothers, and my mum and dad. I slept on the third bunk up, looking down on the lightbulb and ice on the inside of the windows during winter.

Teenage years were tough on the streets, and I was thankful that at 14 years old, music had captured my interest, as the ’60s were starting to unfold into what was to become a very liberating decade. Most of my time was spent going to school, and because there was not much room at home, I used to hang around the streets kicking a ball about or go to The Shaftesbury Boys Club—a great place close to home, where my dad taught boxing—and there were all the usual activities like snooker, table tennis, football, etc.

I also had a paper round and worked at the Mersey Ferries terminal at the weekend selling newspapers, earning money to help at home. When I decided to learn how to play a guitar, the first thing I had to do was buy one, so I was allowed to use some of the money I was earning to buy a Hofner Senator on hire purchase.

Learning to play was difficult in those days. You had to either know someone who could teach you, learn to read music, or buy the Bert Weedon Play in a Day book—which I did—and took it from there to teach myself.

The next problem was, if you wanted to play a Beatles or Stones song, once again, you either had to buy the sheet music or buy the record and learn it by ear by lifting the needle on and off the turntable until you got it. So all of this completely took over my time—until I actually got to join a band.

What was the scene like back in the late ’60s?

The scene in the early ’60s on Merseyside was obviously all about the Beatles and the so-called “Merseybeat” sound—and of course The Cavern, where every band wanted to play. There seemed to be literally hundreds of bands around at this time and loads of gigs everywhere.

But Liverpool was also a big soul music-loving city, and a lot of bands were covering this style of music—though not me—which sometimes created a bit of a stumbling block when I eventually joined a band and tried to get gigs.

However, the scene in the late ’60s, for me, was the era when I believe originality in musical creativity was cemented in the history of rock bands. Virtually all of the bands seemed to have a real style of their own—which is still observed today, hence the tribute bands!

When I think of Zeppelin, Tull, Floyd, Hendrix, Who, Purple, Lizzy, Slade, and many more—all of whom also had some real characters—this wave of incredible differences made me determined to also try and create a style of my own in my writing and performance, as did many of the other bands of the time, which then spilled over and developed into the ’70s.

Did you have any special hangout places?

From when I started playing in my first band I did not really find much time to hang out as such, because I was always gigging or practising, but coffee bars were the big thing in the 60s where most teenagers and band members used to meet up. A lot of these places also used to have live music on at lunchtime, and The Cavern in particular became famous for its “lunchtime sessions,” as until the mid to late sixties it did not serve alcohol, so was available to all ages.

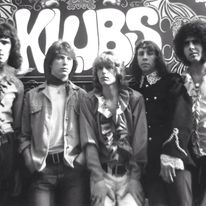

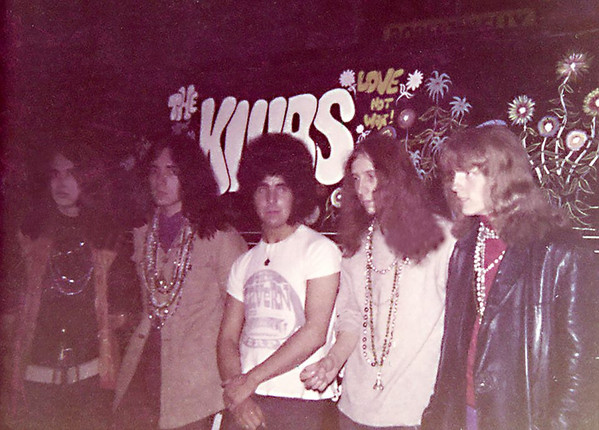

You were originally in a band called The Klubs?

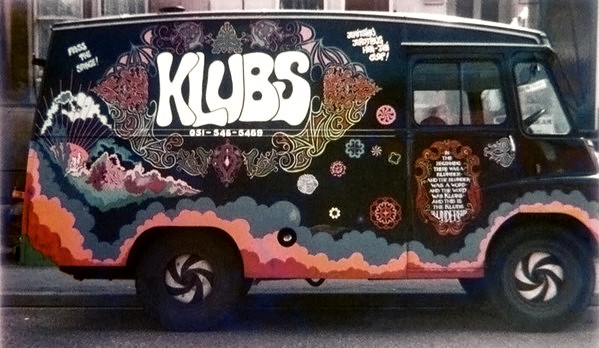

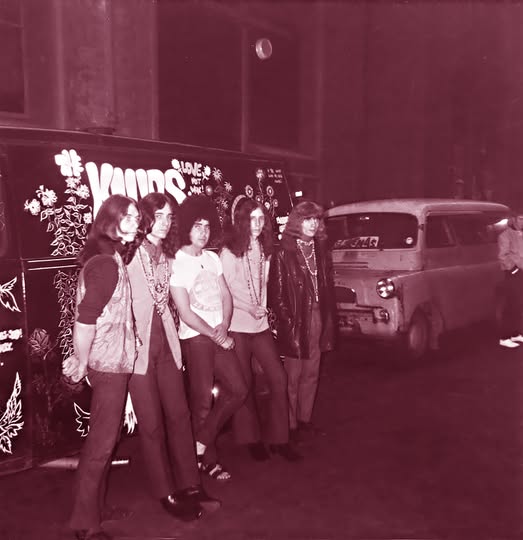

Yes, at the age of 15 I had managed to learn enough to think about joining a band. Two of my friends in school were forming a band and asked me to join as rhythm guitar, which I did. It was initially a 6-piece doing all covers from the Stones, The Kinks, The Who and others. There were several changes to the lineup in the early days but eventually settled as a 5-piece, which lasted a good few years during which time we started to do a lot more of our own compositions. The band became very popular and played all over the UK, and were often billed as “The Wild Wild Klubs”—even the van was quite famous, as it was an old Liverpool police “black maria” which was used to transport prisoners, and we painted it ourselves in a very psychedelic and hippy style. Eventually, around 1968, two of the key members left the band, and after a few more changes it was left with myself, now playing lead guitar, the original singer (who was also now playing bass), and the original drummer—which, effectively, was a 3-piece format that, unknown to me at that time, was to be my future setup with Strife.

You recorded a single? Tell us about it, and also tell us about the early gigs you had with this band…

The amount of stories I could tell about The Klubs and their gigs would fill a book, but I will try and timeline it and get to that one and only single—and then to 1999, about 34 years after I had left the band, when there was a surprise album release.

Early gigs were pubs and youth clubs in 1964, and happily people could not get enough of live music in those days, so they were good times. First real memorable gig was a competition called the “Swingin’ UK Trophy,” organised by the Radio Caroline pirate radio ship, and this was held at The Palace Lido Ballroom on the Isle of Man. Anyway, against all the odds, we won it—which opened a whole can of worms.

To start with, two days before we left Liverpool for the competition, the bass player and drummer chickened out and both left. We found replacements but had no time to rehearse anything—but both new guys said they knew the songs we would be doing. However, when we got to the venue, the new bass player could not play a note! He then told us he only came along for the ride. A phone call home got us another bass player to come over, and we managed to get just three songs together, do the show, and won it. The trophy was presented by Jimmy Savile (yes, him), and along with that came a recording session at Abbey Road Studios. There was also a TV producer amongst the judges who was absolutely blown away with the visual energy of the band and promised some TV time.

However, we did not have a proper band lineup, we only knew three songs, so we had to work fast to pull it all together—which we did, and managed to do the session, with no outcome, as they tried to get us to record a Beatles song called ‘Drive My Car,’ which was really not our style. We also did the TV slot as part of another competition called ‘First Timers,’ which Amen Corner won, so it was back to gigging.

Next, after a good few Cavern gigs, the owners decided that they would like to manage the band—which they duly did. This situation led to us virtually becoming the resident band, because we always pulled a good crowd, but it also meant that we got to play alongside some legendary greats like Chuck Berry and many others. Little did I know at this point that I would be headlining the closing night of The Cavern in the 70s with Strife, making me one of the very last people to play on that original world-famous stage.

In the late sixties we had parted company with the Cavern owners, and another local club owner took on the new role. He had a small record label and wanted us to put out a single. I was writing quite a bit by this time and he insisted on releasing “I Found The Sun,” which was literally one of the first songs that I ever wrote when I was 16 and not really where the band was going by this time—but nevertheless, he went ahead. I was not disappointed when it never really did anything, and shortly after this the band disintegrated as the bass player left and then the lead guitarist, putting us down to a 3-piece, which I eventually left to join Strife.

Then in 1999, a record label called Tenth Planet released a limited edition vinyl album of any material they could find by The Klubs, including bedroom recordings and old demos. It was voted No. 1 album of the year in Record Collector magazine and was titled Midnight Love Cycle—which was another very early song of mine, and people obviously thought was quite psychedelic. This then opened another can of worms when the press got hold of it, and the latest reincarnation of The Cavern asked if we could do a reunion gig. I had played the original Cavern, then the second version, which was in an old fruit warehouse across the road (which later became Eric’s, a renowned punk venue), and now this third and current version, which was built back on the original site—so I thought, why not?

Unfortunately, the original guitarist did not want to do it, so we did it as a 4-piece to an absolute sellout crowd—and it was well worth the effort.

Before forming Strife, did you have a certain idea or even a concept behind the band and what kind of music you wanted to play?

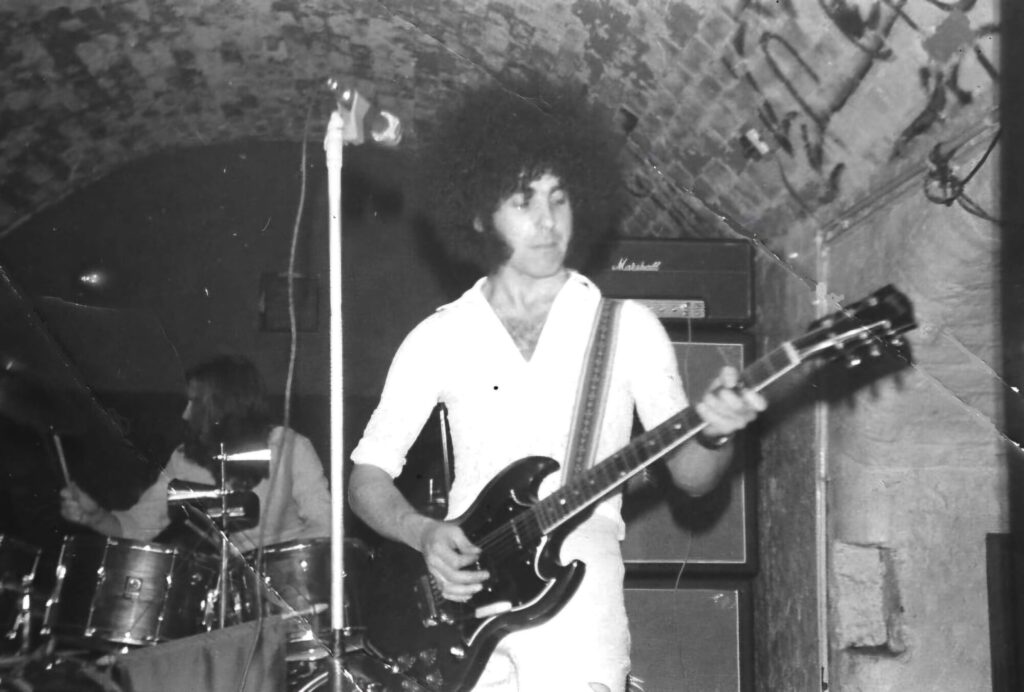

Strife was already in existence when I joined as second guitar and vocals around 1970. I had become friendly with Gordon, the bass player, from various gigs we had played at, and he liked a lot of the songs I was writing. He knew I was no longer happy in The Klubs, so he asked me to join. It was a relief for me not to have to play lead guitar any longer, and I could concentrate more on writing and singing. The reason I was not really comfortable playing lead was that I basically used to hold my guitar like a shovel, and because of that, certain scales and runs were difficult to say the least—making me a three-finger lead guitarist most of the time. But it was me, my style, and that was how I taught myself.

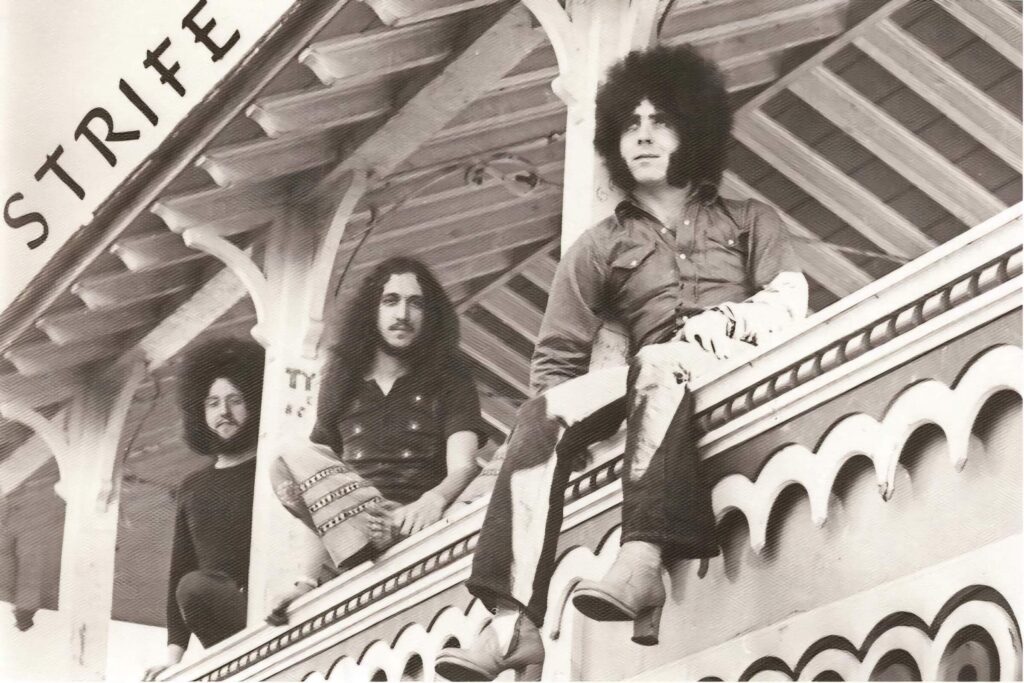

However, shortly after I joined, lead guitarist Pete decided to leave, throwing me back into the lead guitar role, where I was then to stay until 1979. Gordon, Paul, and I discovered we had real chemistry.

I think I always knew what type of music I wanted to play because I was writing it, but Gordon and Paul really brought it to life—just by chance and good fortune. And such was our confidence and respect in each other’s ability that, never ever did we comment or criticise the input each of us made to any song or performance. That allowed the music to flow naturally and remain genuine. I also believe that this mutual respect kept us together as good friends, which we still are to this day.

Without realising, and now with hindsight, my songs were always written with the live performance in mind—which was probably an accidental concept, but one I’ve always accepted. Because playing live is what gave me the greatest pleasure. And it certainly worked for Strife, as we had a reputation as one of the best live bands out there at the time.

How did you get signed to Chrysalis?

By the time 1973 came around, Strife were gigging hard and in demand, but not living in London and being unable to network with record label personnel—most of whom were based there—left us a bit high and dry when it came to getting signed. We did have some contacts, and one of those was in Chrysalis, but despite them having demos, they were still dragging their heels.

We had recently done a gig where Edwin Starr happened to be in the audience, and he really liked the band—one song, ‘Magic of the Dawn,’ in particular, which he said he would like to cover. He arranged for us to do a session with him in London, which we did, but he had to go back to LA before he had a chance to finish it, so the whole thing was abandoned. However, he said if we ever got to LA, to look him up.

A few months later, we still had no record deal, so decided to just go to LA and take our chances. This may sound unreal, but we were walking down Sunset on our second day there, and who should pull up but Edwin. He got us into the car, took us to his house, made some phone calls, and then took us to the Motown offices to meet the people from their alternative label called Rare Earth. We started playing the demo tape when, into the office, came R. Dean Taylor, who also really liked what he heard and said that he would like to produce the album if we got a deal.

I can’t remember how or why, but the next morning we were at a rehearsal studio doing a showcase for The William Morris Agency, who had just lost Grand Funk Railroad and wanted a new three-piece to take their place—and we were it. So much so, that by that afternoon we were in their offices, where they already had the contracts ready.

However, in those days, visas to America were hard to get, and we only had two weeks. They wanted us to stay while they sorted a record deal. They went to great lengths to tell us how everything was going to pan out—where we would be going, what we would be doing, how much money they’d be giving us—so much so that I felt like I was being manipulated by people I hardly knew, and said that we needed time to think.

At this point, they asked us to go and record a song called “Rock and Roll Heaven,” which we reluctantly agreed to do. We went up to Wally Heider’s studios in San Francisco to make the recording. Once again, I felt manipulated because, although the song was a good one, it wasn’t really what Strife were about—so we abandoned the session. Which was probably a mistake, because The Righteous Brothers took it on and got to No. 3 in the Billboard Charts with it.

Again, I can’t quite remember how or why, but we got a message from our friend in Chrysalis who said that they had heard what was going on in LA and wanted to give us a deal. We decided to put the William Morris deal on hold and go and see Chrysalis when we got back to the UK—which we did—and accepted the deal.

Where was ‘Rush’ recorded? What are some of your strongest memories from working on it?

‘Rush’ was mainly recorded at Morgan Studios in London and, being our first album, we were full of anticipation about how it was going to sound in comparison to our live performances. Because of our time in LA, we had a good rapport with Dean and he introduced us to sound engineer Don Gooch, who had done a lot of work with Motown, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Jefferson Airplane, and The Eagles, and he wanted to work on the album too—so it was all systems go. As far as I can remember, we had no problems playing or recording the songs as we had played them so many times over the years.

As for the sound and production, we basically left that to Dean and Don, who decided to take us back to LA to mix it in studios that were familiar to them. My strongest memories of the whole experience were how different it all was from playing live, and Dean bringing in girl singers and saxophones—and not being sure if that was quite right. I do remember Gordon not being too happy about it.

Anyway, at the end of the day I was just glad that we finally had an album out. It was certainly a bit different because of Dean’s production, and whether it was right or wrong, I am still not sure to this day.

Did you do a lot of shows? Did you receive a lot of airplay and press?

We certainly did a lot of shows in the early ’70s around the time the album was released. There was a great club and university circuit, and I think we must have played around 250 nights a year. Chrysalis also gave us gigs as support—the first one being with Leo Sayer and his audience of 10-year-old girls, which did nothing for our cause—then with Procol Harum, who kicked us off after two nights because we were doing too well. Eventually, we got the Ten Years After tour, which was great.

Unfortunately, airplay and press were virtually non-existent, which was very disappointing for us. But what we didn’t know was that there was turmoil behind the scenes at Chrysalis at that time, and the two owners, Chris Wright and Terry Ellis, were about to split. This situation resulted in Strife being held in a five-year contract without the possibility of another album, which basically broke the momentum we had built up over the previous few years.

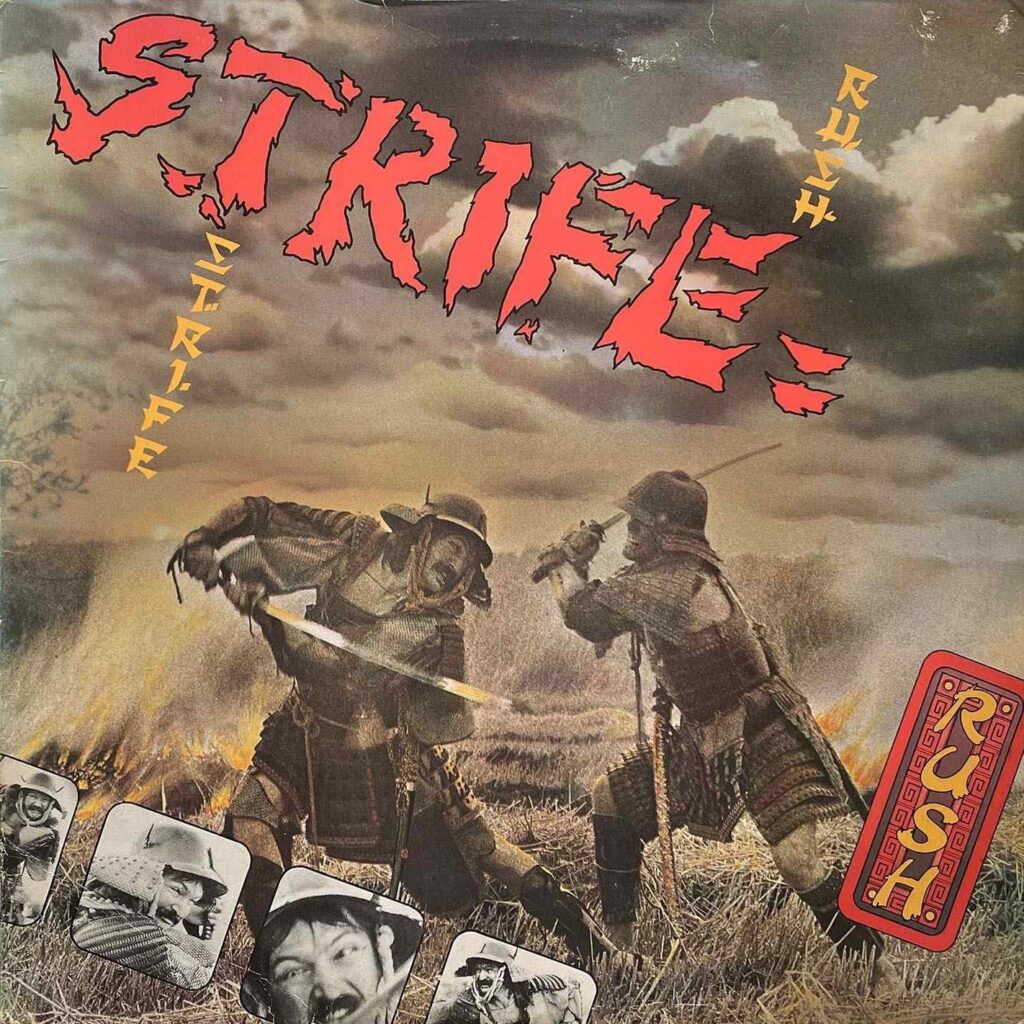

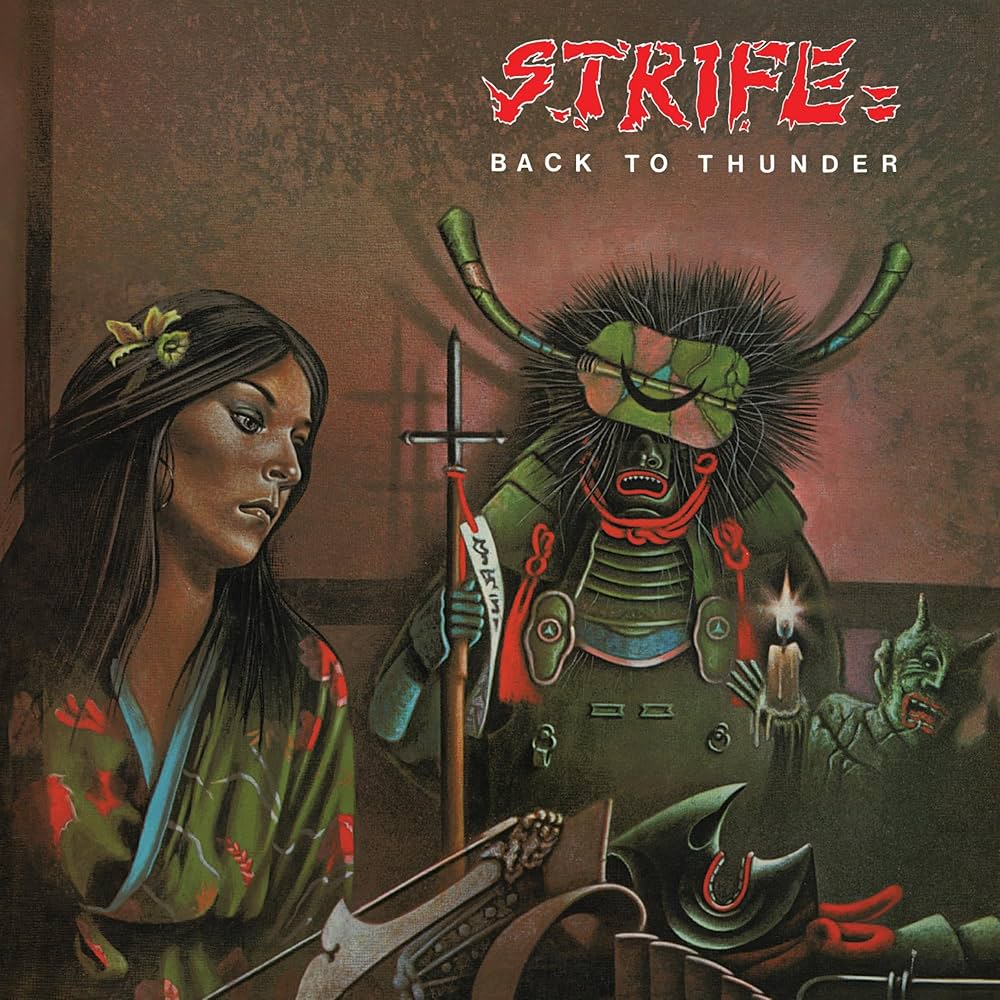

What’s the story behind the artwork?

Chrysalis was responsible for organising the artwork and we had no idea what it was going to be like. When we saw it, we really liked it—especially the logo for the band, which we kept right through to the end. Apparently, the two samurai swordsmen were played by two dentists who took part-time acting jobs, but I’m not too sure if that was true. Anyway, the famous book by Hipgnosis of album covers obviously thought it was worth including in their collection, alongside some other great and better-known bands of the ’70s.

What about ‘Back to Thunder’? What are some recollections from it?

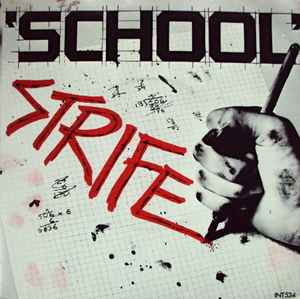

Because we were locked into the Chrysalis contract, we were unable to go and get another record deal without a lot of legal expense. So we decided to create our own record label, Outlaw Records, and release a 3-track EP featuring the songs ‘School,’ ‘Go,’ and ‘Feel So Good,’ which for me is still my favourite recording to this day. We paid for this and produced it ourselves, and were about to release it when EMI approached us, bought it off us, and promised to release and promote it in line with the schedule we had planned. Of course, they never fulfilled any of the promises, released it late, and once again we were let down by the industry.

After this, a few things happened. Our agent Paul King (now deceased) took the Outlaw name and made it into a huge management and promotion company, managing bands like Tears for Fears and Level 42. We took on a new manager, Peter Lyster-Todd, who also took on Kate Bush shortly after and made her into the huge artist she is today. Paul decided to leave the band, and we got a new record deal with Gull Records, and Dave—who was Paul’s drum roadie—took over on drums.

Once again, we went into Morgan Studios to record this album, which this time was going to include a few more tracks that I wrote not specifically for live performances, unlike the ‘Rush’ album. A few recollections come to mind: the first being that I had a lot of trouble getting my guitar in tune. Near the end of the sessions, Gary Moore came in and I was telling him my problem and he said, “Don’t tell me, F#.” I said, “Yes,” to which he carried on to tell me that the room we were in was about to be re-modelled because of this problem—and even to this day, I can still hear it on the track ‘Let Me Down.’

The next event was Sabbath being in the next room doing their album, with the usual antics from Ozzy. In one session, the producer had an idea to bring a large tin bath into the studio, fill it with water, put a condom on a microphone and place it in the bath, then strike a large cymbal and dip it into the water to create a phased type of sound. Next, there was a lot of commotion in the doorway and in comes Ozzy carrying Geezer and throws him into the bath—say no more.

As far as the recording went, I was really pleased that we got Don Airey to play keyboards on a couple of the tracks, which I mentioned earlier as non-live songs. He did a fantastic job, and although they were not really Strife as we were known, I think they deserved a place on the album as they were the more listenable tracks.

Would you be able to draw any parallels?

I think the only parallel I can draw between the two albums was another good piece of artwork on the cover of ‘Back To Thunder.’ In hindsight, I think I tried too hard to write material purely for an album, and because of the amount of time that had passed since the release of Rush, we had lost some motivation and momentum. Then came the departure of Paul, which had a psychological effect, as we had done a hell of a lot together in the previous eight years—and although Dave did a great job on the album and in the live shows, I personally still felt that some of the old magic had gone.

Also, by this time in 1978, a lot of the venues on the circuit that we used to play had changed to either punk or disco, so the number of good gigs had dwindled. So again, in hindsight, I think deep down it was nearing the end of the road. I didn’t realise it, but subconsciously I even wrote in the lyrics of ‘Fool Injected Overlap’ the words ‘E the End,’ and the closing track ‘Weary Traveller’ was probably a sign too. So, a few months after the release of the album—again with no promotion to speak of from Gull—I decided to call it a day.

What would be the craziest gig you ever did?

This may surprise everybody, but despite our stage antics, Strife were quite boring. We never ever took any drugs, Gordon and Paul never drank, and I was only an occasional drinker—but never before a gig. Only Gordon smoked cigarettes. So craziness from our side never really happened. But in actual fact, most bands experienced a crazy life, with a lot of incidents—apart from the performances—happening before or after gigs, or just in the business itself.

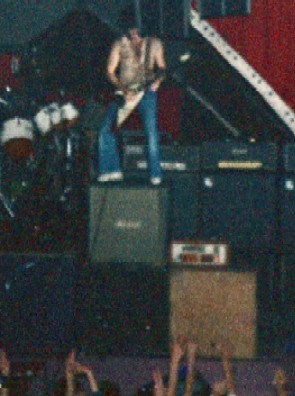

I suppose that I was crazy in around 1970 for climbing onto the top of my stack during our finale, ‘Rush,’ with a strobe light going while still playing—and then leaping off to the joy of the crowds, for nine years. Hence, the two knee replacements I have now had. To this day I never saw anybody else stupid enough to do it—but I’m sure there must have been.

I suppose we must have been crazy to go to Ireland in the mid-’70s during ‘The Troubles,’ this being reinforced by the first gig in Belfast. We were sitting in the band room when we came off stage, and there was an almighty explosion—the whole place shook. This resulted in two of the road crew immediately making their way to Belfast airport to return home to Liverpool. But we carried on with the rest of the tour like lunatics.

I should also mention the craziness of the very early sixties gigs when the crowds were allowed to get right up to the front of the stage. Everybody has probably seen old film of screaming girls trying to get hold of their idols and pull them off the stage—well, this used to happen to The Klubs at some gigs. I’ve often wondered what these girls planned to do if they did manage to capture one of us—but luckily, or perhaps not, this never happened, as roadies always managed to rescue us. Although we did lose a few shoes and boots.

For how long did the band play together and when did you decide to break up?

We played together for about nine years in total, and we decided to break up in January 1979. This was mainly my fault, because—as mentioned earlier—there were a number of negative factors at work which were draining the motivation.

At the end of 1978 I had just reached 30, recently got married, opened my own rock club called The Gallery in Birkenhead, and my first child, Tony, was born. So I thought that if I was ever going to give up playing, then this was the right time. It was an incredibly hard decision after all the hard work, the really good times, and something I had loved doing since I was 15 years old.

Is there any unreleased track or even more material available by your band or even by a related project members were part of?

One thing I haven’t touched on yet was the live show recorded at The Nottingham Boat Club in the late ’70s by Radio Trent, which I later released on my own record label, “Timeline Records,” in 2005 after finding the tape by accident in a box at home. This set did contain one track which was never recorded in a studio called “Before I Die.” The live album was exactly as it was recorded on the night—no overdubs or corrections—and something I look back on as being That Was Strife.

Over the years, both of the studio albums have been re-released on CD by various record labels around the world, along with some bootlegs. In 2017, American label Shadow Kingdom Records released both albums on vinyl and CD, along with some very old, previously unreleased tracks for added interest—but only on the CD version. Even more recently, Rock Candy Records from the UK also released both albums on CD, also with the 6 bonus tracks.

What followed for you and other band members?

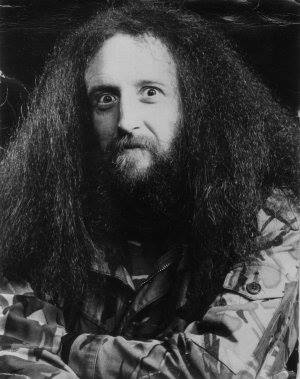

Gordon went on to form Nightwing and released several really good albums which were very successful on mainland Europe. Unfortunately, his health deteriorated to the point where he had to have his left leg amputated and was very ill and confined to bed. However, his mind was still active, and I released a double CD compilation album for him, and then he went on to record a new album titled ‘8472’ with my son Tony on vocals, which I released for download only.

Original drummer Paul never did anything else with music as such, except for the time when we did a reunion gig in around 1989, which was great to do just for the hell of it. Dave went to live in Palm Springs and made a new life over there playing in various bands and became an air conditioning engineer. Unfortunately, he had a stroke a couple of years ago but has recovered well and is still managing to play.

As for myself, I had the club, a wife, and a new baby to occupy my life, so I was super busy. The club was very successful, and I was fortunate that I knew a lot of bands who were happy to come and play—such as Iron Maiden and Saxon (both of them for just £60, believe it or not), Alex Harvey, and many more including a lot of very good locals. I only kept the club for about 3 years, during which time I had my first daughter, Kelly. I bought the property next door to the club to extend, and I opened my first off-licence in the shop part. I eventually changed the name of the club to “Stairways” and sold it. The club went on for many years to become quite legendary locally. I then had 2 more daughters, Charlotte and Amanda. I opened 3 more wine shops. I then got involved with property in Marbella, Spain, sold my last shop about 12 years ago, and basically retired. However, my wife Deb and our daughter Kelly had a vintage clothes business with a large shop in Liverpool called “Raiders,” so I got involved in helping them. They eventually closed the shop and started doing clothes fairs all over the UK, so I effectively became their roadie—driving the van and humping all the gear. This stopped with the outbreak of COVID, and grandchildren have now arrived, so now I spend a lot of time with them.

During all this “life,” I still had a lot of interest in music, especially when the internet arrived and everybody’s music was suddenly very accessible. My son Tony was also now involved in music, so I helped wherever I could and eventually—at the request of some of my old contacts in LA who liked his songs—took him to LA, Nashville, and New York, where he did a showcase for J Records. But it came down to a choice between him and Maroon 5, so you know what happened next.

When digital downloads became a big part of listening to music, I contacted Gull and EMI (who now had all the Chrysalis rights) to ask if they were going to put the Strife albums out there for download, and—as expected—they were not interested. I got permission from them to do it myself and formed “Timeline Records” purely for that purpose. I am very pleased that I did, because with the growth in streaming on all sorts of platforms, it meant that anybody in the world who wanted to hear our music was able to do so via the internet—and it has amazed me how many new people every day discover the band, particularly as it is around 55 years since writing and playing some of the songs.

What currently occupies your life?

The simple answer to this question is not very rock ’n’ roll after everything else that I have done, but to quote a well-worn cliché: Family is everything. So, luckily, I have my wife Deb—having known each other for nearly 60 years and been married for 46 of them—my 4 children, and 3 grandchildren, all of which keep my body and mind very active. Amongst all this, because of the internet, there is always something happening regarding music (like this interview), which makes me so thankful that I did what I did all those years ago.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

The highlight was reaching a point with Gordon and Paul where I felt that we were invincible in our creation of music and performance. We had such an understanding of each other that sometimes, during a soundcheck before a gig (time permitting), we would—and could—just jam for an hour or more without stopping. Just following each other without thinking. It just felt so good to be able to do that.

This connection then created a confidence for us to go and play anywhere, to anyone, and believe wholeheartedly that what we were doing was right for us—which in turn was reciprocated by the vast majority of our audiences. Whether they had heard of us or not, they would give us a great reception time after time. This situation, of being able to go and do a gig where nobody had ever heard of us, never heard any of our songs, no music business hype, was the real measure of the truth about how that audience felt about a band and the songs. No excuses, no re-takes, no overdubs—just real-time, in-the-moment reaction.

So much so, that about 20 years after the band finished, I read on a website about Strife that two guys we used to see at some of the gigs declared they had actually seen the band 59 times. Which absolutely amazed me, but also reiterated the intensity of everything about it.

Then the pinnacle of all this came when we finally got the album released, which then also resulted in one of the lowest points in our time together, when Chrysalis disintegrated and virtually put a five-year hold on our recording career.

It’s difficult to say which songs I’m most proud of, but the first that spring to mind are the three songs we did on our own—and at our own expense—for the EP. ‘School,’ because I really did not like going, and the lyrics came to me very easily. It also became a firm favourite in the live set. ‘Go’ was written in about 30 minutes, just flowed, and was my fastest song at around 153 bpm. In more recent times, it’s even been used by aerobic classes because of that speed—but we very rarely did it live. Then ‘Feel So Good,’ because that was how I felt at the time, and again, it became a firm live favourite.

However, I suppose I’m most proud of ‘Rush,’ the title track of our first album and always the finale in our set. It had so much in it, and it was a true reflection of how the three of us connected musically. Whenever I hear it, I’m always amazed at all the different pieces—especially when I hear the live version from the ‘Rockin’ The Boat’ live album. I often think: how the hell did we do that?

I probably did thousands of gigs over my 15 years of performing, and so many were memorable for very different reasons. To choose just one is almost impossible—so if you don’t mind, I’m going to list a few in approximate date order, and then I might just be able to pick one out.

Winning the Radio Caroline Swingin’ UK Trophy in the Isle of Man with The Klubs when I was just 16 and still at school was probably the first. Then, in 1968, at an all-day concert at the Liverpool Stadium, The Klubs played in the afternoon, followed by The Move and Pink Floyd. However, the promoter was so impressed by our performance that he insisted we go back on after Floyd and close the whole show.

Again with The Klubs—playing with Chuck Berry at The Cavern—because he was such a legend.

Then the first one with Strife: a small gig in Liverpool when Gordon was electrocuted by touching the mic stand while still holding his guitar. He was thrown to the floor, and I remember the mic stand lying across his arm, which I kicked off. His mouth was black, with smoke coming out of it. I’m not sure to this day if he was actually killed at that point—but luckily, there was a nurse in the crowd who gave him CPR and obviously saved his life.

Playing at the Watchfield Free Festival in 1976 was also memorable—mainly for the fact that it was filmed by a local TV company. To this day, it’s the only piece of film footage of Strife, which is a real shame considering we were such a visual band. However, I managed to salvage it from the Sony U-matic tape and it’s now on YouTube for all to see—even if the quality isn’t great and it’s in black and white.

The final one I’m going to list was actually one of the very last gigs that Strife did. It was the final gig of the Ian Gillan tour at the Marquee Club in London. I was invited by them to get up and play during their encore. John McCoy, the bass player—who was a big guy—hoisted me onto his shoulders while we were playing. Then I heard another guitar join in, looked round, and it was Ritchie Blackmore. Apparently, Ian and Ritchie had not spoken for a few years, and the road crew had arranged this surprise, which worked out great for everybody—Ian and Ritchie, the crowd, and of course myself. So perhaps this was the most memorable one.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours…

As people get older, there is one word that pops into their minds a lot more—and that is “hindsight.” Now, at 76 years old, I use it a lot. This interview has brought back a lot of memories, and I’ve barely scratched the surface. But I’ve realised that I don’t have any regrets about spending the first 15 years of my adult working life in a band.

I’ve found that hindsight has not given me regrets—but more of an understanding as to why things did and didn’t happen. There are comments frequently written on social media about how great they thought Strife were, and how they couldn’t understand why we didn’t make it. At the time, I often thought the same thing myself—especially when we had bands in their early days, as our support acts, such as Judas Priest, Motörhead, Supertramp, and others, who—rightly so—went on to do great things.

I’ve come to accept that there were probably many reasons why it never happened for us. But to a degree, I am a believer in fate—and it was just not meant to be. Again, in hindsight, I’ve also realised that I don’t think I would have enjoyed the intensity of being famous—with endless touring and the pressures of constantly having to write better songs. This feeling was confirmed, subconsciously, by the previous reference in L.A. when we refused the William Morris contract.

So, in a nutshell—I loved being in a band, I loved performing, I loved writing songs, and now… I love the memories.

Klemen Breznikar

Strife YouTube