Liquid Len (Jonathan Smeeton): The Man Who Painted Light for Hawkwind and Beyond – An Interview

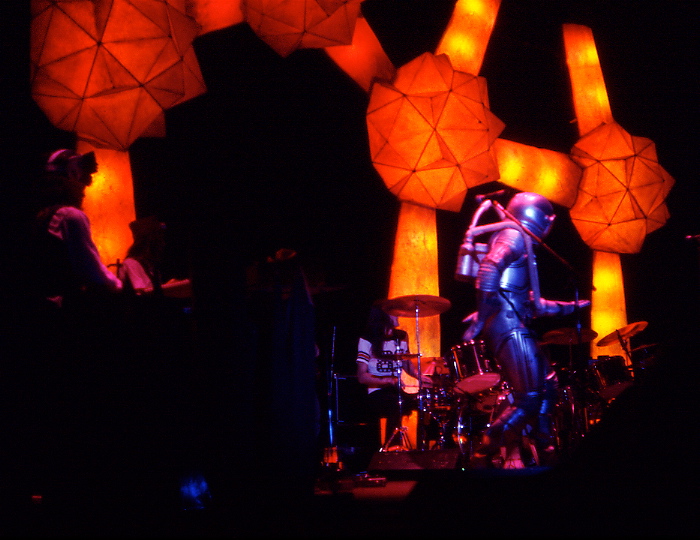

Liquid Len, a name synonymous with the wild, freewheeling days of Hawkwind, was the mind behind the band’s mind-bending light shows in the early ‘70s.

It wasn’t just about the music—it was the whole trip. “It wasn’t just lights,” he says, “it was about creating a world where you could lose yourself.” And lose yourself you did. With his custom-built rigs and liquid slides, Len turned every Hawkwind gig into an evolving piece of psychedelic art, where the visuals and the music collided in a cosmic swirl.

But Len wasn’t just a Hawkwind staple. After leaving the band, he went on to work with the likes of Frank Zappa, Peter Gabriel, and Black Sabbath. While Zappa’s shows were all cerebral chaos, Gabriel’s were visual storytelling at its finest. But Len always maintained that the light wasn’t just a gimmick—it was as much a part of the band as the sound. “Lighting is art,” he says, “it’s about making something that sticks with you long after the show ends.” A true underground legend, Len’s work was more than just about lighting—it was about creating a whole experience.

“I still count the best cue I ever executed was just one light on… and then it went off.”

Let’s start with the very beginning. The UK underground scene in the late ’60s — what was the first moment when you realized that lights could be more than just illumination, that they could be part of the show, a form of storytelling?

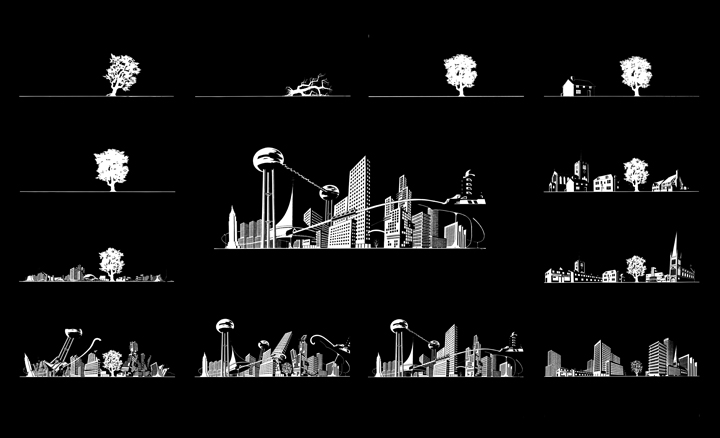

Jonathan Smeeton: I realised one could tell a story some time into my working with Hawkwind. I came up with a sequence of slides known as City and Tree, which became famous in its own right. Simon House wrote an accompanying piece of music, although I think Dave Brock is credited for that piece of music since. Basically, it started with an old oak tree (which dissolved between two projectors), to a tree with a cottage, then a village, a small town, a Victorian town, a post-World War II city, to a futuristic city, which then crumbled and fell down, leaving the old oak tree, which in turn died, fell over, and was gone. All the while, dark blue clouds scudded behind it, all projected from a slow rotation disc wheel in a third projector. See attached poster yet to be published.

Were you a psychedelic visionary from the start, or did you stumble into the liquid light vortex by accident? What led you from the counterculture into lighting design — were you experimenting with projections at home, or did you fall into it through a scene connection?

I first started into lightshows by accident. Needing a job, I went uptown London from Kingston-upon-Thames with a couple of mates. Toby knew of a club that was opening, Middle Earth in Covent Garden. Toby had already worked in a club, “Cousins”, an all-night folk club in a cellar on Greek Street in Soho. He got the job of running the coffee bar. John, my other friend, said he’d do anything, and got the job of janitor. When asked what I did, I told them art student. “Oh! You must know about these new psychedelic light shows.” Yes, I lied, and that was it. I was now running a lightshow before almost anybody else.

From that, I started running a lightshow at UFO, which had just moved into the Roundhouse in Camden Town. And the rest is history.

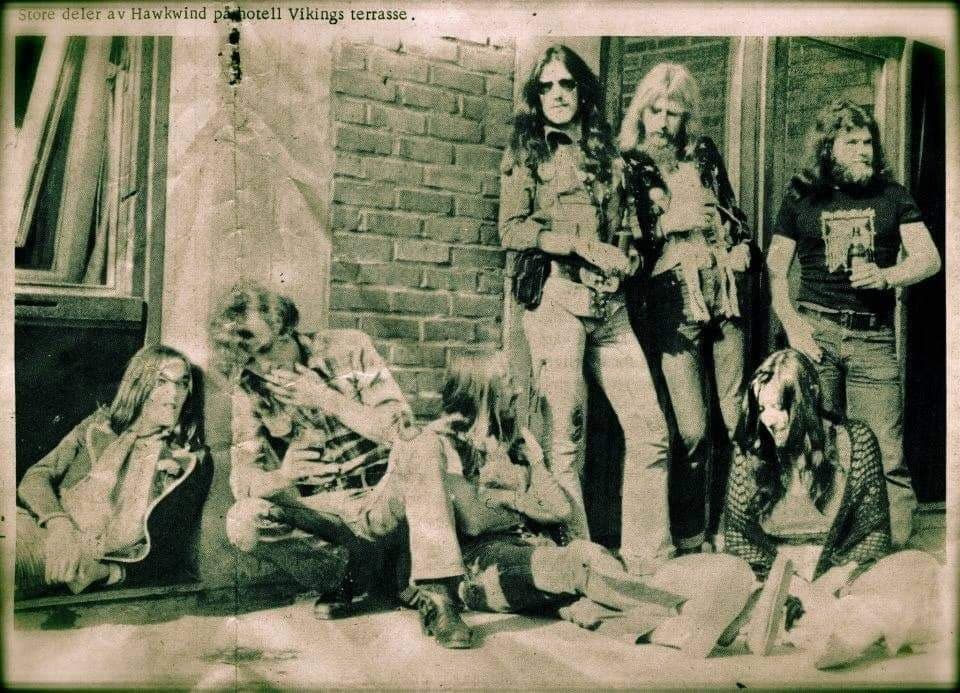

I spent a year in Scandinavia putting on lightshows in art galleries, paid for by the Swedish Arts Council. When I returned to England, I lived in Notting Hill Gate and found myself a job as a projectionist at the all-night cinema club, The Electric Cinema on Portobello Road.

Island Records had just opened a studio on Basing Street, just up the road, and I just popped in, offering me and my lightshow. Chris Blackwell, the owner, told me lightshows were worth ten a penny, but if I told him I could provide touring stage lighting, he had a gig for me.

The next week, I met up with him armed with the Strand Electric hire catalogue and told him I could provide stage lighting. And off on tour I went with Traffic, Free, Mott the Hoople, and Jess Roden. The Island Records tour. Mostly city town halls.

The rest is 50-odd years of history.

The first time you saw Hawkwind live — before working with them — what did you think? Did it feel like the kind of band that needed your brand of lighting sorcery, or was it more like, “this is chaos, and I must tame it with photons”?

I never saw Hawkwind before I worked for them. I knew Doug Smith, their manager, from the Portobello Scene, and he was looking for a lightshow. My first gig with them was at Chiswick Town Hall.

I turned up at three in the afternoon, but the place was locked up. It didn’t occur to me they would arrive at five o’clock, so I just went away. I can’t remember when I first did a gig with them.

It was a bit of a bodge, really, as they already had a couple of people providing a lightshow but could only do weekends as they had proper jobs. The three of us worked together on and off for about a year until the time of ‘Silver Machine’ hit, and I took over full-time and solo.

The name Liquid Len and the Lensmen — was that purely a nod to E.E. “Doc” Smith’s Lensman books, or was there something else at play? Did you see yourself as the visual equivalent of a sci-fi warrior illuminating the spaceways?

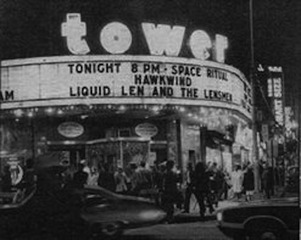

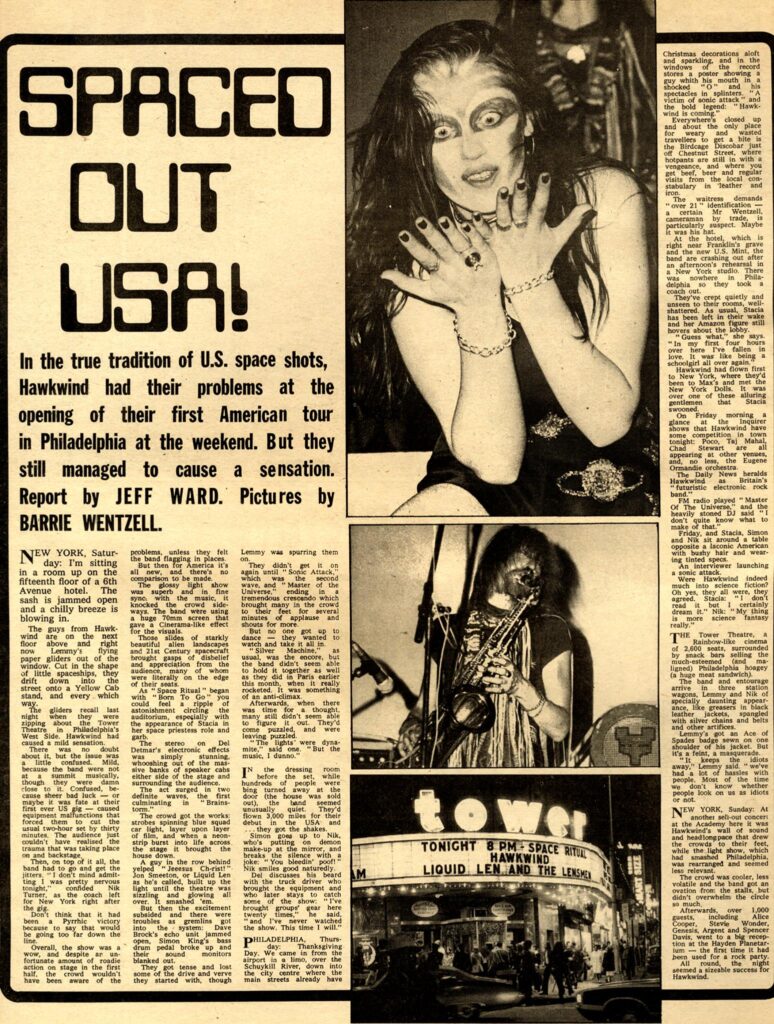

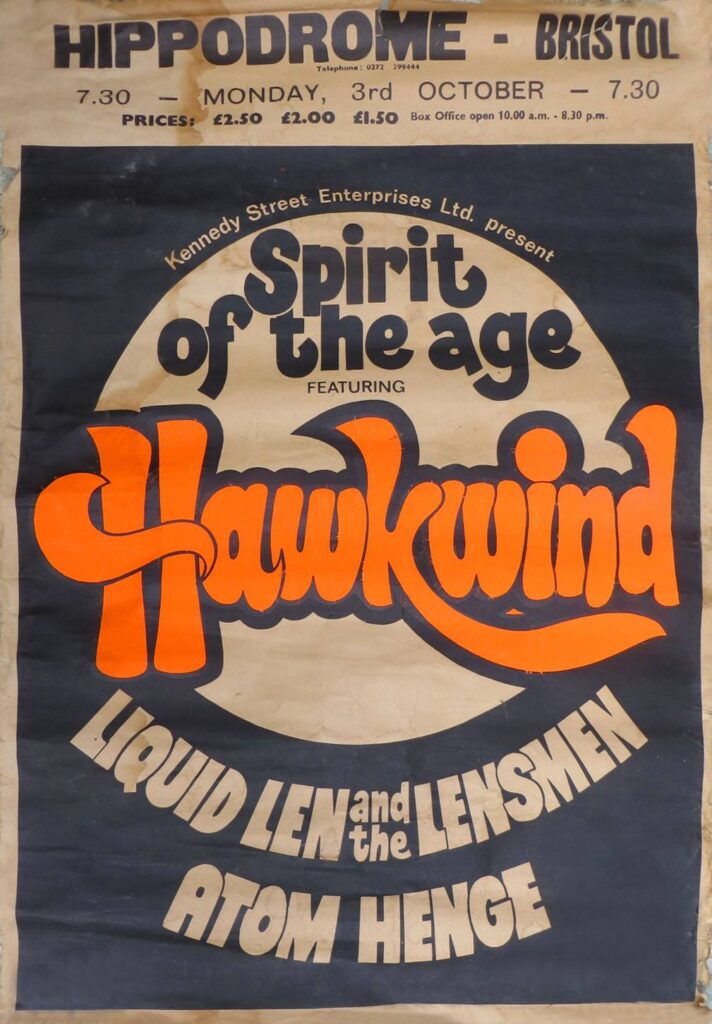

We were about to go touring in the USA, and Doug Smith, the manager, asked me for a name of the lightshow, as he wanted to put it on the poster billing and facade outside the theatre, as it would seem lightshows got billing in the States.

At that time, I had just read an article about the invention of a liquid lens that could change focus and, at the same time, had just read Doc Smith’s dreadful sci-fi tale.

Well, I thought it all a bit of a joke — billing, names, and so on. So my thinking was it should be a pun on the way Motown and Detroit bands named themselves. Somebody and the So-and-So’s etc.

Liquid Lens became Liquid Len and, of course then, and The Lensmen.

Take us inside a Hawkwind show in 1971. What were the mechanics of making the light show happen? Were you rigging things on the fly, controlling it all manually, or did you have a set plan?

In 1970, having worked for Island bands, I found myself being employed a lot by Traffic, Free, and Mott the Hoople on their own stand-alone gigs. I worked with Traffic and Free for a year or more. I provided simple stage lighting, but Steve Winwood wanted a lightshow, so he sponsored me to build the equipment I had been dreaming about but had put on the shelf due to getting into stage lighting. In a few weeks, I had it done. Three Aldis 1000-watt projectors from my original show, five GAF Anscomatic slide projectors, and two Aldis II’s converted to 300-watt CSI light sources. Five three-light 500-watt footlights. Dimmers, all controlled on what we called The Colour Organ. Basically, it was a controller operated via an electronic piano keyboard. I had a girlfriend, Sally, who was a brilliant painter, and she produced all the still images. Within a year, I had the whole thing rebuilt, having learnt the hard way all the pros and cons and, of course, coming up with new ideas. I even ended up with foot pedals controlling overall brilliance.

What was the wildest thing you ever projected onto a stage back in the Middle Earth/UFO days?

In those days, it was all very basic. Liquid lightshows were the be-all and end-all.

I, like the few others doing lightshows, used a transparent glass stain called Vitrina, no longer manufactured. By removing one of two heat shields from the lamp, the heat would boil the stain, causing it to bubble and boil. I also used black Indian ink quite exclusively, which also boiled but in a totally different way—and being black, one only saw the bubbles, which were coloured with gel or even ink in a separate layer of glass. One has to remember the audience were all pretty stoned. They were the wild element you enquire about.

Any memories of crazy mishaps with the ink and glass slides? Ever set anything on fire?

I remember once going to Liverpool for an early Hawkwind show and suddenly remembering I hadn’t packed the glass plates we used to make the liquid slides. Sat in the back of the van, washing old slides in a bucket of water we got from a canal somewhere on the M6 motorway.

Other than that, all pretty much organised. Have seen other lightshows go up in flames, mostly poor wiring and the odd experiment with inflammables.

You mentioned building your own dimmers and lights out of wood. Looking back, do you think those early DIY solutions helped shape your creativity later on?

My first effort of footlights were wood and ordinary 100-watt lightbulbs. But then I went up to 500-watt photofloods, which got really hot. Fortunately, I found a metal workshop that made steel encasements for me. Three lights per frame with gel frames: primary red, dark blue, and primary green.

In reflection, I was put off making stuff myself; I found getting stuff made by professional manufacturers far more practical. So I became the designer and delegated construction to others.

I bet the strobes and visuals during early Hawkwind concerts were so intense that people would black out or feel like they were slipping into another dimension. Did you ever see anyone actually lose themselves in the lights?

I used to get a lot of feedback from punters, usually all very positive. They certainly paid attention. I think a lot of people got caught up with the visuals, especially later on when we started to use storylines. Fifty-odd years later, with the advent of video reinforcement, I found myself making short movies to tell the story. Taylor Swift was a fine example of that—all her songs had a story to them.

With Journey in the mid-80s, video was in its infancy and only used to amplify the glamour on stage for those up in the gods. Hawkwind, on the other hand, were much more abstract.

Hawkwind was a band of contradictions—science fiction meets biker chaos, structured jams that could explode into total improvisation at any second. How did you match your lighting to that unpredictability?

Certain songs had certain routines which I always stuck to. Basically, a start, a middle, an ending or transition into another start. Whatever went on with the band was up to them—a lot of the improv was predictable. Bridges and middle 16’s were often their own chaos in the making; I just kept on going until they changed. Pretty obvious when they were about to change—lots of signals from drummers, nods and winks from the band.

What was life like on the road with them?

I’ll quote Dickens at you.

“It was the best of time and the worst of time.”

Mostly a time of missed opportunities.

In my corner, a time of incredible discovery, learning, and fuel to do more and better.

Was there ever a show where everything went totally off the rails—lights failed, power blew, the band got too spaced out to function? How did you handle those moments?

In my time, we had a few moments but nothing so serious as to stop the show. Not that I can remember that much detail anymore. Before my time, I do recall the story: Simon King got to be the second drummer just in case Terry Ellis fell asleep at the wheel. How true a story that is, I don’t really know.

The only time I lost power altogether was just a few years ago with Diana Ross. She had just walked on stage and out the lights went. The audience then lit her up with their cell phones until all was restored.

Having shared a room with Lemmy, do you have any stories that are even remotely printable?

I spent about three years rooming with Lemmy, before that a couple of years with Nik Turner, one night with Dave Brock, and a French tour with Bob Calvert.

Lemmy was the best, we always got along, I saw him in L.A. the week before he died. Always a good friend to the very end. As for stories… best not told.

You’re immortalized in Genesis’s ‘The Battle of Epping Forest.’ Did you know at the time that you were being name-checked, or did someone play the album for you later and say, “Hey, Liquid Len, you’re in this”?

Years after, while working for Peter Gabriel, he apologized for using my Monica. Didn’t know about it until I saw it mentioned on a Wikipedia page about me.

As you moved into working with bigger acts in the late ’70s and ’80s—Peter Gabriel, Frank Zappa, Black Sabbath—was there ever a sense of nostalgia for the madness of the Hawkwind years, or were you relieved to be dealing with more structured productions?

Never looked back, except when I worked on the Hawklord project. Then I only looked forward to getting back to my new normal.

What was it like working with Frank Zappa?

Brilliant! Frank was the most intelligent person I ever had the pleasure of working for. We got along very well, even years later when I had moved to Los Angeles. We used to meet up every so often. I always hoped he’d get into politics. He would have made a good President in my opinion. But he was way too clever for that.

Touring with bands like Traffic, Free, and Mott the Hoople, was there a particular moment when you realized that lighting was about to become a huge part of live shows, not just an afterthought?

In hindsight, I always thought lighting and scenic design was more art than practical, certainly a big part of storytelling.

You worked with Peter Gabriel for a decade—what was the most out-there idea he ever had for stage lighting?

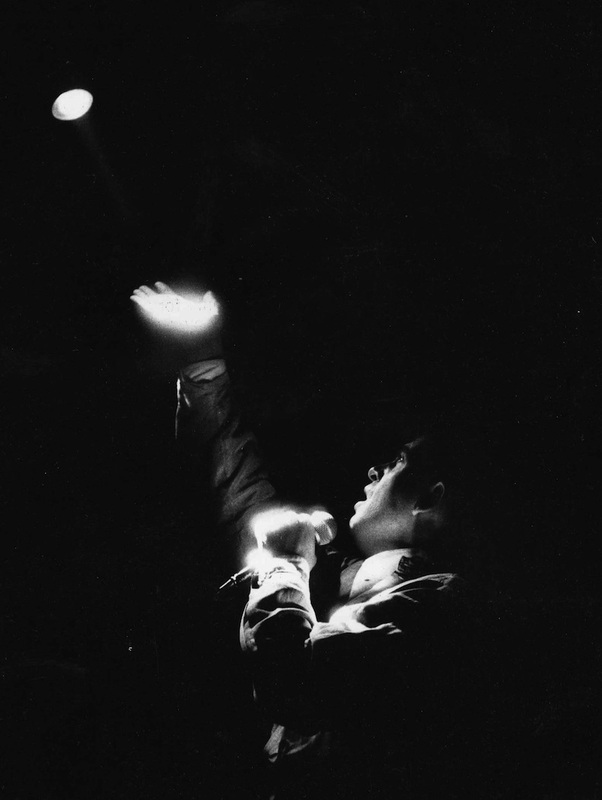

Actually, Peter never had lighting ideas, but we had a connection that really worked. He was a great storyteller and making the place in which he performed quite easy. Very scenic. He was quite into interacting with the light about him. San Jacinto, a song about an American tribal boy becoming a man, with a line, “I hold the light, the light that sustains me,” was a great opportunity. Peter would grasp a beam of light from one of my array and run his hand up and down it. It was a great moment, but when I put a mirror in his hand it became stunning. In the end, after many variations, it became just one light on Peter, relighting himself from the hand mirror. And then panning the beam around the audience… fade to black.

You saw the Vari-Lite for the first time at a Bowie show. Do you remember the exact moment when it clicked that lighting was about to change forever? You’ve seen lighting go from manual control, oil projectors, and strobes to complex digital rigs and fully programmed shows. Do you think something has been lost in the transition from human-driven chaos to precise, automated lighting?

I got it the moment I first saw them move. Changed everything.

Unfortunately, it was also the beginning of our lighting business becoming a global industry, which I feel took away a lot of creativity.

I look at modern shows nowadays and see very little originality. Quantity instead of quality.

I still count the best cue I ever executed was just one light on… and then it went off.

But what do I know?

Thank you for some of the most intelligent questions, I actually enjoyed remembering and answering them for you. And now, I finish my wintering here in Tennessee and the Gulf Coast in Alabama, back to Gloucester where my canal boat is moored, and sail off into a few sunsets.

Klemen Breznikar

Jonathan Smeeton Website