‘Perfect Teeth’ Turns 30: An Interview with Unrest’s Mark Robinson

Unrest’s ‘Perfect Teeth’ turns 30 this year, and to mark the occasion, the band is reissuing their shimmering swan song with a bonus album of EP cuts, B-sides, and other rarities—fittingly dubbed ‘Extra Teeth.’

Out now via TeenBeat and 4AD, this deluxe set includes remastered audio (mostly from the original tapes), new artwork from longtime collaborator Chris Bigg, and a 16-page art zine featuring liner notes from the band and 4AD founder Ivo Watts-Russell.

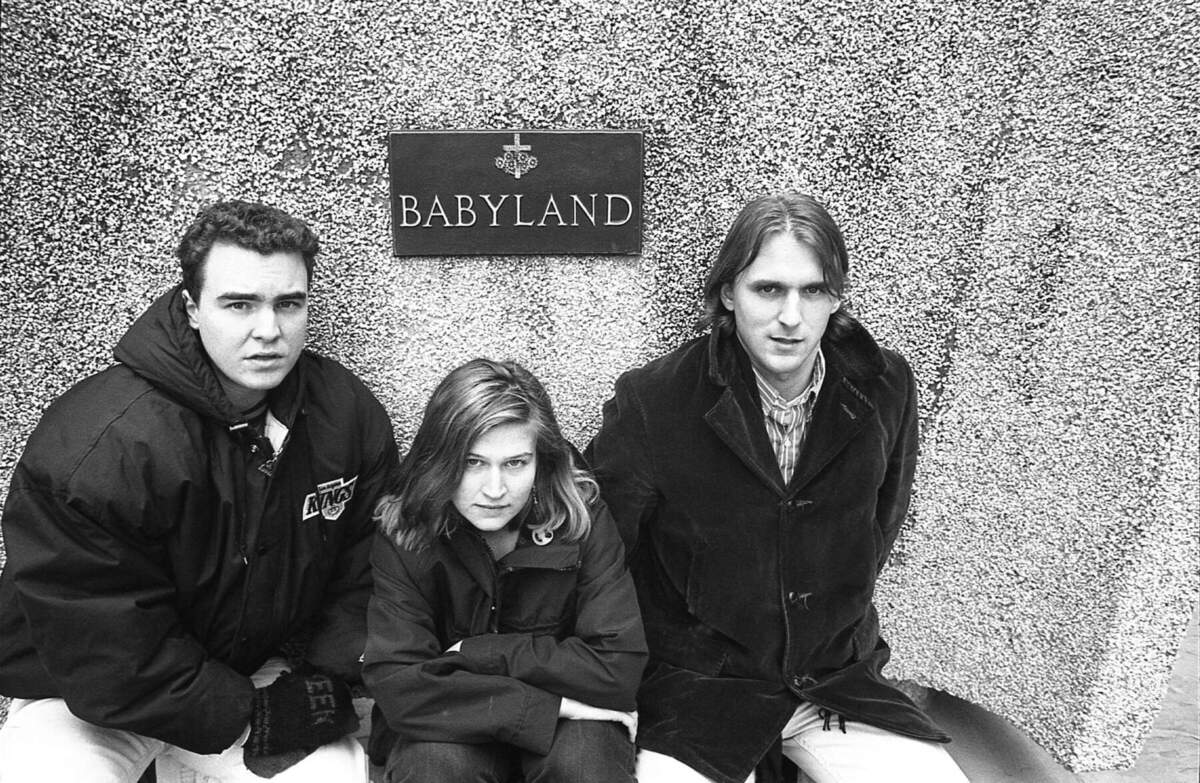

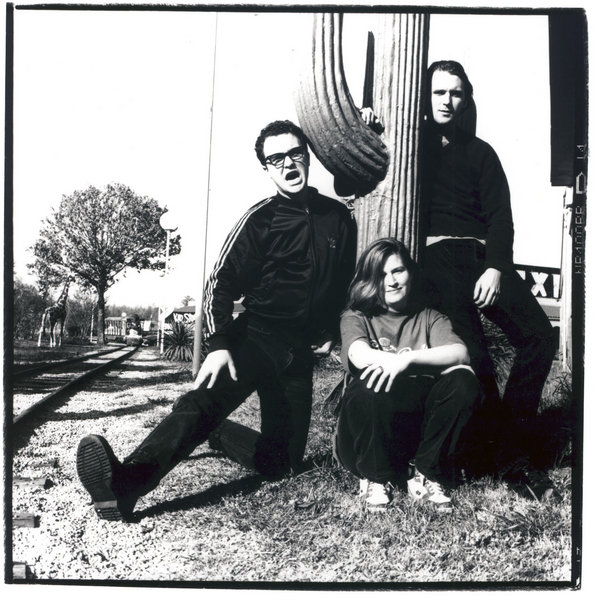

Formed in 1983 in Arlington, VA, Unrest made their name through a fearless mix of DIY weirdness, jangle pop, and art-punk left turns. ‘Perfect Teeth,’ their final album from 1993, is all polished edges and underground sparkle, featuring the classic trio of Mark Robinson, Phil Krauth, and Bridget Cross (ex-Velocity Girl), and recorded at Pachyderm Studio just after Nirvana wrapped ‘In Utero.’ The new edition finally does justice to the full scope of what made Unrest so quietly radical and endlessly replayable.

It’s available now on digital and physical formats—double LPs in various colors, CD, and a stripped-back black vinyl version. It’s a celebration, a time capsule, and for some of us, a reason to believe in indie rock all over again.

“A lot of my songs are just pure emotion”

Mark, Unrest’s music has always felt like a series of restless impulses colliding—eclectic, chaotic, yet somehow incredibly controlled. Did you ever feel like you were trying to outrun your own success, or was it always about shaping something more difficult and complicated than just being “another indie band”? What was the music trying to escape from?

Mark Robinson: I’m not sure I was trying to escape something other than music that sounded like all the other bands. Generally, I was just trying to make music that I liked and tried to make it as different and entertaining as I could just to please myself. That sounds pretty selfish, but I think that’s how it works for artists that stand out—and that was something I aspired to. Whether or not I achieved that is up to others to decide, of course!

You’ve always had a knack for making music that’s both cerebral and accessible, but it never feels like you’re trying to make people comfortable. Do you think there’s a danger in indie rock becoming too self-conscious, too concerned with its own legacy? How do you keep from being sucked into that trap of overthinking and losing the spontaneous edge?

We weren’t purposely trying to make people uncomfortable, but we did like to keep it interesting by doing all sorts of things—attempting as many genres of music as possible, and trying to keep things fresh and surprising.

In some ways, ‘Perfect Teeth’ feels like an album that’s both of its time and timeless… like it could only come out in the ‘90s, but it still feels fresh today. Do you think the era shaped you, or did you shape the era? What’s your take on how much your work was a reaction to the mainstream, versus how much it was just about creating something that had to exist, regardless of what was popular?

I think I was primarily shaped by my childhood in the 1970s and 1980s. And as far as musical aesthetic goes, top 40 music of the ’70s, classic rock, hardcore punk, and UK indie music of the early ’80s seem like my main influences. By the ’90s, I think we were already fully formed. I suppose it would be nice to say we helped shape the era in some way—but who knows. And if so, hopefully we shaped only the good parts of the decade.

“We always went all out”

‘Perfect Teeth’ feels like a culmination of all the experimentation you’d done up until that point. What was the headspace like when you were working on it, especially knowing it was your last album? Were there any moments of hesitation, or was it more of a “this is it, let’s go all-in” kind of thing?

We didn’t know it was going to be the last album. I already had plans for the album after that just a month or two later. My working title was “Air Jamaica” and I had even sketched out some cover designs. I think we were still experimenting. “What can we get away with?” “What are we capable of?”

We had the same attitude with each record. We always went all out. We always recorded more songs than would fit on the album for singles and compilation tracks, etc., and we always recorded something that was pretty weird that usually only we would like. The real creation of the album came in song selection and sequencing. That always set the mood and dictated what the album sounded like—how we wanted to come across. For instance, with ‘Perfect Teeth,’ there were quite a few short, lighthearted, breezy tracks that could have completely changed the feel of the record if we had included them. I’d love to hear if people have any sequence ideas when they hear the rest of the songs on ‘Extra Teeth.’

You’ve mentioned in the past that Unrest’s music was a reflection of your surroundings and the scene at the time. Can you talk about what the Washington, D.C. area—especially in the ’80s and early ’90s—was like and how it shaped your approach to music?

I was a huge fan of the bands in the D.C. punk scene, which was referred to as D.C. hardcore. Minor Threat, Marginal Man, Government Issue, Iron Cross, plus lots more. And other bands like Velvet Monkeys, No Trend, Tru Fax & The Insaniacs, Rupert Chappelle, Egoslavia, Tony Perkins & the Psychotics, Grey March, Slickee Boys, Tommy Keene… There are really way too many to count. I can’t really think of a local band that I didn’t like.

You worked with Brian Paulson on Perfect Teeth, and he had already worked on ‘Spiderland’ by Slint. How did his approach to recording influence the way the album turned out? Were there any particular challenges or benefits to recording in Pachyderm Studio so soon after Nirvana?

Brian’s approach to recording was strategic microphone placement and getting the best sounds he could. I still marvel at my guitar sound—which, of course, had a lot to do with the guitar and amps—but to transfer that onto the recording, he spent a lot of time and did an incredible job. Same with Bridget’s bass and Phil’s drums. There was an isolation room for the drums, but he decided to let Phil play out in the big room with us, which gave those drums an extra bit of punch.

I’m not sure we knew that Nirvana was going to be recording there until we got to the studio compound and were told they had just been there. Kurt Cobain’s wife Courtney Love had been there as well, according to the assistant engineer Brent Sigmeth. Since it was so remote and far from the city, it was a residential studio with rooms for the bands to stay in as well as a heated indoor pool. It was one part vacation and one part studio session.

The reissue of ‘Perfect Teeth’ brings a whole new generation of listeners to your work. How do you feel about the lasting legacy of the album? Do you ever find yourself discovering new things about it when you listen back to the remaster?

Some of the songs I hadn’t heard in years, so it was fun to revisit them all. We recorded about 20 songs and 11 ended up on the record. I remember not liking a couple of them at some point but was nicely surprised when I heard them again. They weren’t so bad and were, in fact, good—if not great. Haha.

We discovered a vocal version of ‘Hey Hey Halifax’ (on the second LP, ‘Extra Teeth’) that I had forgotten about. It sounded pretty unfinished, so we didn’t include it on the expanded album, but it brought me back to that time in the studio hanging out with Bridget, Phil, Brian, Brent, and Simon.

As far as the legacy goes, it seems like people like it, so that’s very cool. A lot of people have said it’s timeless and sounds fresh. Keep it coming. I’m guessing that people who think it sounds old and dated are most likely keeping to themselves.

The bonus album ‘Extra Teeth’ is filled with rarities, EP tracks, and songs from split releases. How did you choose the tracks that would make it onto the bonus album, and what do these songs reveal about the band during that period?

We tried to include everything that we recorded at the session at Pachyderm. We almost succeeded, but the 30-minute ‘Hydro’ was too long to be included. Perhaps we should have put it on the CD or the streaming version. Chris Bigg, who did the artwork for the original and the 30th anniversary edition, also wanted to include the ‘Isabel Bishop’ EP material, since he had designed that as well and it paired well visually with the design of ‘Perfect Teeth,’ as it was released just a few months earlier.

On songs like ‘Cath Carroll’ and ‘West Coast Love Affair,’ there’s a strong sense of narrative and character. How much of a role does storytelling play in your songwriting? Are these characters entirely fictional, or do they have any basis in your personal experiences?

A lot of my songs are just pure emotion that comes out in bursts with the lyrics, are somewhat abstract, and really just set the mood. But, like you’re saying, with some of the others, there’s a narrative—though it might be somewhat blurry or unintentionally cryptic.

I can’t speak to ‘West Coast Love Affair’ since Phil wrote and sang that one, but that one certainly paints a picture.

The DIY philosophy of TeenBeat Records is a big part of Unrest’s identity. Looking back at the label’s beginnings, how do you think your approach to running a label affected your approach to the music itself? Did you feel more freedom or pressure in that environment?

Early on, the label TeenBeat and Unrest were pretty unified. DIY (do it yourself) was certainly the theme and our template. There was really no choice. No one was going to help us do anything, and even if there was someone who would have, we wouldn’t have known where to find them. It took us three years to even figure out how to book a show at a club and not just our high school’s talent show. We were young and had no idea about anything.

You’ve always had an eclectic taste in music, with everything from punk to folk influencing Unrest. What are some of the less obvious influences that people might not know about, but which played a key role in shaping the sound of Perfect Teeth?

When we recorded the original version of ‘Cherry Cream On,’ called ‘Cherry Cherry,’ we added a coda to the end of the song. We were recording at Fun City studio in Manhattan with the great Wharton Tiers. The studio was in his basement. We recorded with him more than anyone else—two albums plus countless singles and compilation tracks. He had a lot of percussion instruments—so many different types of bells. We really wanted to try them out and played almost all of them in a cacophonous, noisy end to the song.

The inclusion of the coda was inspired by a couple of bands who had done something similar. ‘Crispy Ambulance,’ on their ‘Live on a Hot August Night’ 12” single, had recorded a song called ‘Concorde Square.’ It’s a three-minute song with a six-minute drone at the end. The whole thing was so striking. Another band that we all liked was King Crimson. They similarly had a very long song—two minutes of “song” and 10 minutes of improvisation at the end. It really changed how you felt about it. ‘Moonchild’ also had a lot of the bells. We carried that on to the recording of a few songs on our album ‘Imperial f.f.r.r.’ as well as onto ‘Perfect Teeth.’ You can hear that in ‘Light Command’ and ‘Vibe Out!’

Even though a lot of our songs were set structures, we loved to improvise within that structure, and the coda allowed us to do a lot of that. Then there are tracks like ‘Food & Drink Synthesizer’ that are completely improvised.

Now that you’ve had time to reflect on the entire Unrest era, what are you most proud of in terms of the band’s legacy, and are there any aspects of your work with Unrest that you feel didn’t get the attention they deserved at the time?

We received way more attention than we ever could have imagined when we started in 1983–1984. I suppose some songs that may not have gotten as much attention as others would be single B-sides, but generally, of course, the tracks that people like the most get the most attention, and I think that’s fine.

What currently occupies your life? And what’s on your turntable?

I continue to operate the Teen-Beat label. I spend most of my time designing and creating new things with Teen-Beat catalog numbers, whether they’re new albums or other cool things that I design.

On my turntable frequently is ‘All Life Long’ by Kali Malone — a minimal organist. So good.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Unrest (1993) | Mark Robinson, Bridget Cross and Phil Krauth | Photo by Erin Smith

Unrest Facebook

Mark Robinson Facebook / Instagram

Teen-Beat Website / Facebook

4AD Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube