The EVEN MORE Freewheelin’ Jeffrey Lewis: Rambling Through His New Record

Jeffrey Lewis is the kind of guy who can turn everyday weirdness into something unforgettable, and on his new album, ‘The EVEN MORE Freewheelin’ Jeffrey Lewis,’ he’s got us all following along, no matter how strange the journey gets.

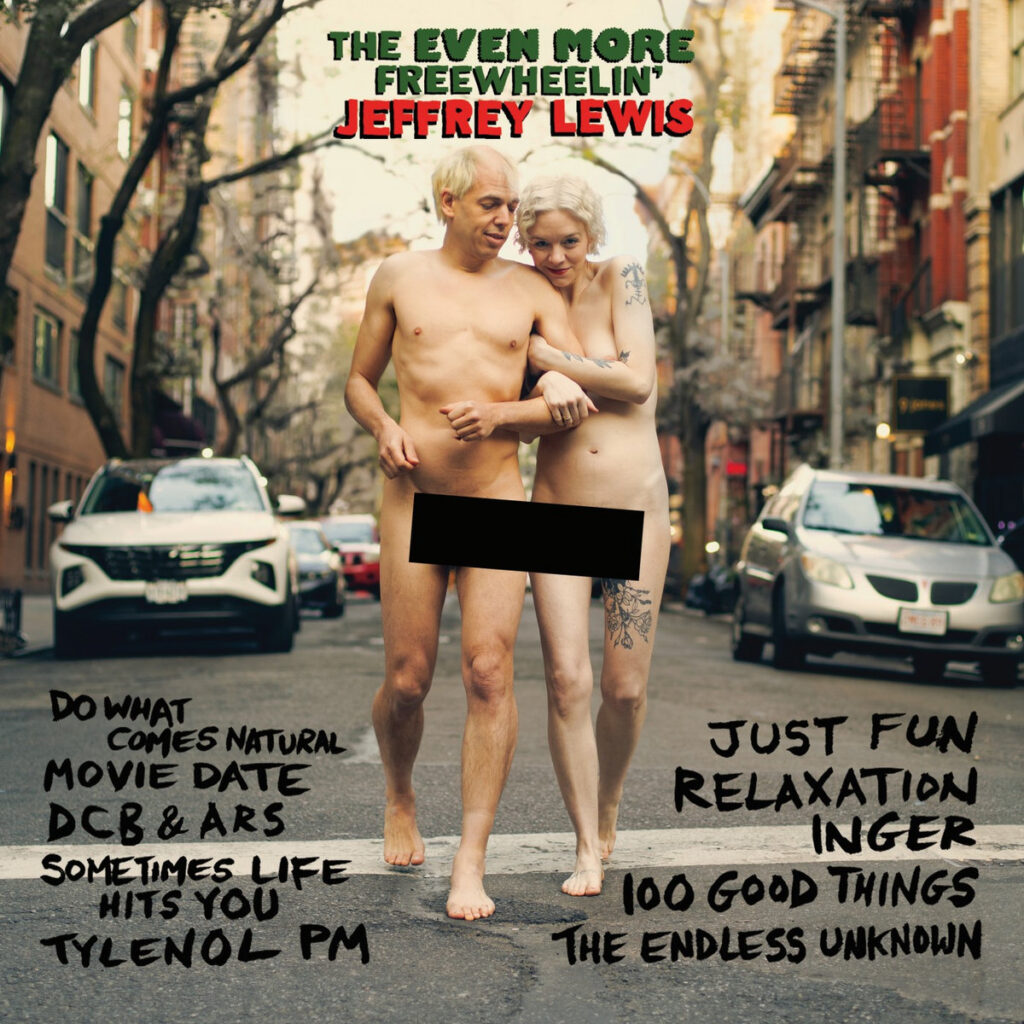

In 1963, Bob Dylan bundled up in a suede jacket and leaned into Suze Rotolo’s shoulder as they wandered through the streets of New York. It became one of the most iconic album covers of all time, ‘The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan.’ Sixty years later, Jeffrey Lewis figured he could do Dylan one better. Same street, same pose, but no pants. Even more freewheelin’, right? Only problem was, global warming had other plans. No snow. Just slush and soggy streets. Still, the spirit stuck and it floats all over Lewis’s new album ‘The EVEN MORE Freewheelin’ Jeffrey Lewis,’ which was out March 21 via Blang Records and Don Giovanni in the US.

The album feels like classic Jeffrey Lewis, but a little sharper, a little sadder, a little funnier. Recorded in just four days in Nashville with producer Roger Moutenot and his Voltage bandmates Brent Cole, Mem Pahl, and Mallory Feuer, the whole thing hums with a raw, lived-in energy. The first single ‘Relaxation’ drops you into a dizzy loop of bad-trip folk rock, the kind that starts gentle but ends with guitar pedals freaking out and bass lines twisting around your head. It even comes with a lyric video full of flashing lights and comic book speech bubbles, like a window into Jeffrey’s slightly warped brain.

Lewis has always carved out his own weird little spot in music. Too smart for the punks, too messy for the folkies, too honest for the cool kids. The EVEN MORE Freewheelin’ doesn’t try to change any of that. It just reminds you why he’s still one of the best we’ve got, whether he is fully dressed or not.

“Trying to be a band I would be the biggest fan of.”

‘The EVEN MORE Freewheelin’ Jeffrey Lewis’—the title, the cover, the whole concept—feels like both a loving nod and a cheeky challenge to Dylan. What does Freewheelin’ mean to you, especially now, 20+ years into your career?

Jeffrey Lewis: Do you mean what does Dylan’s album mean to me, like Freewheelin’ with a capital F as a noun, or what does freewheelin’ as a verb with a lowercase f mean to me? I usually consider Donovan to have been a bigger influence on my early songs when I was in my early 20s, first learning guitar and first making songs, but the early Dylan stuff was part of my guitar-playing inspirations too, for trying to learn how to do stuff. I had been a fan of the early Dylan albums since a few years earlier, but I remember I had recently gotten a tape of the ‘Bootleg Series Vol. 1,’ which is a lot of his non-album stuff from the 1962 era of The Freewheelin’, and a lot of that material was pretty big for me when I was first starting to make songs and go to open mic nights, like in 1998, age 22-ish. I was super immersed in Donovan, Pearls Before Swine, the Alexander Spence ‘Oar’ album, and the early Dylan stuff when I was living in that West 28th St apartment, making up the songs that were on my first tape, that first year after college. I always wondered if the title Freewheelin’ was supposed to be Dylan’s joke on people pronouncing his name wrong in his early years—like, before he was well-known, maybe people were reading his name as if it rhymed with freewheelin’ or something? I’ve never read that anywhere; I just thought maybe that’s why he had that album name, with the apostrophe. It’s hilarious that he says he later added an extraneous “g” to the name John Wesley Hardin because he “owed the world some Gs” or something like that.

The album was recorded in just four days in Nashville. That’s practically a Ramones-level speed run. Did that urgency shape the final sound? Any moments where the pressure cooker made something special happen?

We were supposed to have a week to record, but the producer called and said he was unfortunately suddenly sick in bed with Covid right when we were all about to fly to Nashville. We didn’t have the money or the scheduling leeway to do anything other than just get on the flight because the housing and flights were nonrefundable at such short notice. So it wasn’t just that our time to record in the studio got limited, it was also that poor Roger was kind of just dragging himself out of bed into the studio to try to record us as best he could despite feeling crappy, just so that we’d get at least a little bit of use out of our trip. But four days is enough—it’s not like we were trying to make some ‘Sgt. Pepper’ album. We had the songs, we knew how to play the songs, it doesn’t really take that long. I remember thinking that the version of ‘Relaxation’ that we used had a guitar solo that I thought was my worst, but Brent and Mem and Roger were happiest with that take because of the drums and bass parts, and in retrospect I don’t hear anything wrong with it. I don’t remember why I thought I’d done it badly. Really, to hear an extremely rapidly made album, you’d have to hear our album 2023 ‘Tapes’ on my Bandcamp page—that was like 17 full-band songs recorded, mixed, and released in one day. We recorded that in NYC and it sounds totally fine to me; I don’t know what would be different if we had a week or a month to work on it. When you hear stuff about Elvis and his band doing 57 takes of ‘Hound Dog’ or things like that, it’s hard to believe, or it’s hard to imagine what would be so different about the takes. Somebody would need to explain that to me.

There’s always been a self-aware, wry humor in your work, but songs like ‘Relaxation’ also lean into a kind of existential unraveling. Do you think of your songwriting as a way to process anxiety, or is it more of a performance of that anxiety for the listener?

I don’t have a way to filter or control what each song gets written as; I’m always just working from a basic desperation to write anything at all. When I’m sitting with a notebook and a guitar, beggars can’t be choosers—I’ll just write whatever song I can write. Sometimes it’s what you’d call cringy, or embarrassing in some way, or sometimes it’s somehow off-brand or awkward. The filtering comes into it later, when I’m trying to decide what songs to play at a gig, or what songs to put on an album. I think to hear the full range of stuff that I’ll make up within any year, you could listen to the “tapes” that I’ve been releasing on my Bandcamp page at the end of each year for the past few years—that’s all my “extra” songs. I don’t know if the anxiety thoughts are overall the most present kind of songs among all the songs that get made each year, versus other kinds of topics. I’m trying to focus on the songs that seem just like the best songs to me—stuff that just seems to work the best to play or to listen to, whatever the topic is—and then there’s all the other ones that just end up shunted aside into my pile of songs that don’t get played. It’s therapeutic to put things in song form because it just becomes a song at that point—it becomes something you can step back and look at. As for the performance of the song, I used to think that the ideal situation was like a documentary where you’re capturing a real emotion happening in real time, but I think that’s only possible when you’re doing that first home recording of a song that you just made—when you’re actually crying or laughing while the recording is happening because as the performer you’re also hearing the song for the first time while you’re playing it.

Your lyrics often balance absurdity and heartbreak in a way that’s so distinctively “Jeffrey Lewis.” What’s your personal metric for knowing when a song has hit the right balance?

I think of it like baseball, though usually only Americans would know the details of that game. It’s the rules where you’re trying to hit the ball with the bat, but if you hit it and it goes too far to the left, or goes too far to the right, that’s a “foul ball” and it doesn’t count, and you have to try again. To me, with songs, I think of that as a song that’s too silly on one side, or a song that’s too mopey and glum on the other side. I hit a lot of those “foul balls,” and you can hear some of those on my albums too, but the ones that I think of as the best ones are the ones that are hit hard in the correct zone — not too light, not too dark — but with enough of both to feel truer to my sense of life. There’s a richness of feeling from that overview, the mix of all those aspects; those are usually my favorite ones.

But I’m often wrong about which ones hit the listener the way they hit me personally. Like, I get very struck by my tracks like ‘Not Supposed to Be Wise,’ but it’s pretty far from being among my most known recordings. And then there are ones that I wouldn’t think of as among my top best songs, like ‘Cult Boyfriend,’ that end up being more associated by the public as “the best Jeffrey Lewis songs,” so what do I know. I like that song enough to put it on an album and play it live sometimes, but I would never think of it as being in the same league as ‘Back to Manhattan’ or ‘Scowling Crackhead Ian.’

Also, there are songs that are so youthful to me now, like ‘Life’ or ‘Back When I Was 4,’ where I will still play them out of respect for the 22-year-old Jeffrey that wrote them, but I would, or could, never write those now from where I’m at in my 40s. I’m willing to let go of my sense of controlling these things; I’m sitting back and watching the weirdness of what is coming out of me and then what is becoming of it. It’s like watching fire or some other transfixing natural process — it’s just weird and unpredictable and interesting to me for some reason.

You’ve always had a DIY philosophy, from bedroom tapes to comic book zines to self-made tour documentaries. What’s the hardest part of staying independent at this point in your career? And what’s still exhilarating about it?

People seem to think it’s a choice, as if every artist has all the options laid out in front of them in a supermarket and they just choose their preferred option. It seems to me that it’s more like being the homeless person outside the supermarket panhandling — you don’t know what is going to come your way, and all you can do is try to make the best out of whatever each day’s circumstance is. If there’s a nice hotel to sleep at, sure, I won’t say no; or if there’s some grubby couch stained with cat piss, I mean, I need to sleep somewhere, so what else am I going to do?

I don’t think I’m any different than anybody else in just trying to apply my creativity to each day’s circumstances and trying to make some choice that seems the least regrettable. If anything, if I’m any different from anybody else, it’s just in how low my standards are for what seems okay to me, maybe from how I was raised. My dad used to say, “If you can eat anything and sleep anywhere then you’re free.” And then, obviously, it was hearing Daniel Johnston that inspired me to be able to make songs and recordings in the first place. Comic books were always like that for me too, from a very young age — it was something I could do just because you just do it; nothing can stop you. Just seems like a basic obvious approach to things — you do what you can do.

As for what’s exhilarating, it’s always been mostly that feeling of making something that I’m excited about — making the kind of song I would want to hear, making the kind of comic book I would want to read, playing the kind of show I would want to see, trying to be a band I would be the biggest fan of.

The band on this record—Brent Cole, Mem Pahl, Mallory Feuer—feels incredibly locked in. How does collaboration work for you? Are you a benevolent dictator, a democracy enthusiast, or more of an “everyone fend for themselves” kind of bandleader?

I usually try to do a thing where I let the various musicians have a chance to come up with their own inspired arrangement parts; sometimes they come up with something I couldn’t have thought of. But then a lot of times I might want to adjust things, or I hear them do something and I’m like, “That, that thing you just did — I think you should do that over and over in those sections.” Sometimes I like their ideas better than mine or vice versa.

My brother Jack, who was always playing bass in the band since the early days, usually has the kind of approach that I prefer, so it often happens that I’ll try to play through songs with Jack whenever I have the chance, and then I might tell my bandmates to play things that are similar to what Jack was coming up with. So Jack still has a sort of ghost input in the aesthetic in some places.

There are some times when I let myself get overruled, or where I feel like I’ve been too much of a dictator on a certain song, so I’ll let a bandmate dictate the parts on the next song a bit more, just to be diplomatic — even though sometimes I regret it later if it was on a recording.

But the last couple albums have been made with the working philosophy that it’s much better to go into the recording studio after all the songs have been getting played live for a while, so the arrangements have had a good amount of time to evolve and settle in. That way, we’re not wasting studio time — we’re already really good at playing and singing the songs and we already know what all the parts are. Then the other benefit of that approach is that any fans who are coming to the concerts after hearing the album can be impressed at how well we play the songs live, because the studio recording is not a studio creation that’s outside of our actual ability to perform.

Your music has always straddled folk and punk, but in a way that never feels forced—like Pete Seeger covering the Dead Boys. When you write, do you think about genre at all, or does it all just flow out in a big downtown New York City mess?

I don’t think I ever thought of it as folk-plus-punk when starting out on this stuff that’s been my path. I was more just aware that there was something I really liked about recordings made by people who didn’t seem too professional. It was this realization that I liked Syd Barrett better than later Pink Floyd, and I liked the stuff where you could hear all the mistakes, like in the first two Velvet Underground albums, or the first Fugs recordings, and Daniel Johnston’s tapes and the early Bob Dylan albums, including the 1965 electric stuff, and also ’90s stuff I was hearing like Sebadoh and Palace and Yo La Tengo, where the aspects that were messy, like the noisy guitar or the uncertain vocals. Oh, and totally the early Ween albums—that stuff was really big for me and my brother Jack too. So I realized that this kind of thing could be more enjoyable or powerful to listen to and it could be something that I could participate in making myself, and it was cheaper. I listened to a lot more classic rock than anything else, but then hearing Syd Barrett’s stuff was the first gateway to this more personal kind of creative idea—to be able to be really creative and colorful and also sometimes get really unguarded, rather than posturing to be something you can’t really be. I could fully embrace that kind of thing. Most things that are called folk-punk I don’t really relate to—there’s something suburban about that stuff, and there’s something very addiction-oriented about it, lots of songs about alcoholism or opioid addiction, and lots of sort of tragedy-porn about how many people they know who have died or stuff like that. There’s nothing wrong with that aesthetic and that American narrative as an artistic realm, but it has basically nothing to do with me. I think a lot of those people do good work, even if it’s unappealing to me in some ways, with their sort of “frantic” style or overdramatic emotional vocals, but it’s a geographically and culturally really different zone than me.

“I’m just trying to be understood”

The concept of “anti-singing” comes up a lot when people describe your vocal delivery, but it feels more like an intentional rejection of artifice than anything else. Who are the singers you’ve always admired, despite—or because of—their imperfections?

Yeah, I do tend to think that what people call “singing” is generally unappealing to me—it seems like a put-on. It doesn’t contain anything; it’s the most shallow and flimsy con. If there’s anything good about singing, it’s when the person’s personality is represented, and that might happen when somebody has a conventionally developed skill set or it might not. You can’t find a better singer than Mark E. Smith, and you can’t find a worse singer than Frank Sinatra. Also, I think a lot has to do with who’s writing their own songs. If somebody isn’t singing their own songs, then it’s harder to get a satisfying sense of artistry from whatever fake vocal warbling is going on—it’s people pretending to be other people who are pretending to be other people, without any foundation of an actual opinion or perspective or brain or emotion. If I try to think of people who are singing with technical proficiency while simultaneously baring themselves as humans, maybe I would think of Morrissey, or Michael Jackson, just as a quick brainstorm—I could probably think of other people. But the reverse isn’t necessarily true: having an undeveloped singing voice doesn’t automatically mean that somebody is being interesting or sincere or brave.

For myself, I’m just trying to be understood, and I’m trying to avoid falling into a straitjacket of performer roles, especially standing on stage with a guitar—there’s only so many ways that your body and face can move. There are these obnoxious roles that I don’t want to fall into because of how annoying it looks to me when I see people enacting those things. I’ve spent a lot of time at open mics seeing dozens of performers each night. You accumulate a list of things not to do when you see how unappealing it looks for people on stage to be pulling certain moves, trying to fulfill certain roles. Like that camel-neck head-bobbing thing when playing guitar, to show how into the groove you are—I hope I never accidentally start doing that. It’s so embarrassing to be on stage looking like you’re trying to act like something or other, but it’s hard to sidestep all those traps. I just want to get the song across in its most understandable form.

I’m trying to do this in my comic books too—just some sort of meat-and-potatoes functionality—but people say that I have a recognizable style. It’s just what emerges from me doing my best to get the fundamental job done. I’m trying to hone and master my ability to get from point A to point B.

You’re a storyteller, not just in song but in your comics and spoken-word pieces. What’s a great story you’ve never been able to turn into a song, no matter how hard you’ve tried?

There’s no such thing as not getting it done if you try. There are songs I haven’t finished writing because I stopped putting time into finishing them, but I don’t believe there’s anything I’m unable to write—you just write it. Whether it comes out in some way that seems effective or compelling or delightful or engaging, that might not be the result, and there’s a lot of stuff that I make that I don’t think comes out particularly keep-worthy.

The historical songs are great challenges, like ‘The Story of Chile’—sometimes it seems impossible to do, but then all I have to do is sit down and do it, and then it gets done. I have an unfinished thing about the American banking system—that’s obviously kind of a dry subject. I had a bunch of stuff written down and a few lyrics taking shape, but I never finished it. There was a thing I was starting to write about the history of the Ukraine-Russia conflict, but that material ended up discussed in my comic book issue Statics #2 instead of in the song format that I was working on. There are also topics like my life of sexual failure that I think work better in comic book form, because I think it gains narrative power from being a sort of longer shaggy dog story of ridiculous repetition, though I’ve put that in songs too.

Meanwhile, a song that tells a beautifully condensed, pocket-sized version of a huge topic—like the French Revolution—is something that appeals to me too.

Your discography is like a diary, tracing everything from New York rent struggles to philosophical spirals. When you listen back to older records, do you recognize yourself, or does it feel like hearing the thoughts of a completely different person?

I do recognize myself; I did what I could at the time. It’s a different person, I respect him, and I’m okay with receiving his royalties as his next of kin—he’s like a relative. But I say that from the limited tunnel-vision perspective of the 3-D entity that is me here and now, and I know that I’m wrong. Because from a 4-D perspective of an overview of my shape in time, then it’s all very accurate as a Platonic Jeffrey-ness, a persona-shape which actually is only a finished shape at the point when I stop carving it. Each new album or new project redefines the whole project, I think, and changes the relationship of the previous stuff to the full sense of it. But that’s probably only true as far as you keep it part of one uncut thread, by continuing to create. Like, each new Lou Reed album continued to expand the portrait of the artist that ultimately formed his overall epitaph when he ceased, but the Rolling Stones stopped redefining their own catalogue a long time ago.

One thing that’s strange to me about my earlier songs and recordings and comic books is for me to think about how many things I hadn’t discovered yet, like, I can’t believe I didn’t start discovering Jonathan Richman’s albums until a certain point, or any number of things I hadn’t yet read or heard or seen or lived. But that must be the same for anybody making stuff.

You’ve been in the game long enough to see entire waves of indie folk, garage rock, and “anti-folk” acts come and go. How do you think your approach to making music has evolved—or stubbornly stayed the same—since the late ’90s?

I feel passionate about what I like, and then I thrive on the stubborn challenge. I don’t think those people had much interest in vision or tenacity in the first place; they usually just had some sexiness that gave them the opportunity to be the avatar of representing carnality or fertility in that cultural-technological moment until somebody else grows into that role and they grow out of it. My approach is just creative desperation, and I’m still desperate, so I keep poking around for any possible way out, like a rat trapped in a garbage can. Sometimes I find a little morsel of satisfaction to keep me going.

The new album’s cover art makes a statement, but it’s also undeniably funny. Is there a moment in your career where you took a creative risk that you thought might bomb, but instead it totally worked?

The History of Communism stuff that I do in my gigs, that’s kind of a weird thing to try to do, or sometimes I’ll have a quick idea for a song or cartoon and I’ll post it online without thinking it through too much, and then I brace for waking up to find out I’m cancelled. I’ve bombed and screwed up a lot, especially in the earlier years when I was trying a lot of things, or when I was living in Austin, Texas, and nobody knew me and I could try so much different stuff at the open mics. Or, like, putting out the album of Crass covers, I had no reason to think that would be appreciated. I fail a lot more than I succeed; there’s a lot of risks that end up detrimental. I’ve gotten better over the years, but for example, I still insist on playing a different set list each night on tour, and that creates some sub-par situations.

You’re hitting the road again for a big UK/EU tour. Do you have a pre-show ritual? Any superstitions, weird routines, or venues that feel like home no matter how far from New York you are?

My set-list writing method is a bit of a daily pre-show ritual, where I try to consult my notes about what I’ve played in that city the last few times I was there, so that I can hopefully avoid playing any of the same songs I’ve previously played in that city, though for some cities it becomes impossible because I’ve played there too often. There are a lot of venues that feel like familiar places, especially in the UK, places I’ve played so many times, like the Brixton Windmill in London or the Adelphi in Hull or the Musician in Leicester or other places like that, but also in the USA some places like Chop Suey in Seattle or the Mercury Lounge in NYC. They’ve been around a long time, I’ve been on some of those stages over and over for decades. Some places you swear you’ll never go back to, and you hope your career outlives theirs!

If you could time-travel back to your teenage self—maybe that kid making tapes in a Lower East Side apartment—what’s the one piece of advice you’d give him before he sets out on this whole journey?

I didn’t start making these songs and recordings till I was in my 20s, so the only advice I’d give my teenage self might be to draw even more. I was drawing a lot, but I had a limited time in life before the internet started, and I should have drawn as much as possible and worked out as many ideas as possible before the internet came and turned the human soul to mush. My whole artistic career is just running on the fumes of the fact that I was able to generate enough of an artistic soul prior to the onslaught of the cultural warping inherent to the technologies of the 21st Century. My comic books and my music are little life-rafts of a pre-internet brain sailing for 25 years through the melted reality of the 21st Century. Can you imagine having 20 years of no internet time? That would give you a very unfair advantage as an artist. Also, I would tell my younger self to cut off the ponytail earlier. I didn’t know I would have such a limited time to try out different hairstyles before baldness. I basically stubbornly spent about age 15 to 27 with just one hairstyle, which was just to never cut my hair. But then I only had about three years of opportunities to try different haircuts, at least regarding haircuts involving the top of my head.

Let’s wrap up with Tuli Kupferberg. If you could sit down with Tuli for a conversation today, about music, the world, or just life—what do you think he’d have to say? And what would you want to tell him?

I was fortunate enough to have a few years of having Tuli as a character in my life. I can still hear his voice leaving his idiosyncratic hilarious voicemail messages and stuff like that. He was born in 1923, so his sense of resigned cynicism about the politics of the human race was very long-honed through more waves of experience than we can really fathom today, if you can possibly imagine a personality like his having lived through all the events and eras that he did. Just think of each one of those decades that he lived through! The 20s! The 30s! The 40s! The 50s! The 60s! And so on! I suppose I would be curious to ask him which time period he thought was the worst, because I have this feeling that every era probably seems like the worst ever at the time. So the current situation where it seems like things are so apocalyptic and depressing, it would be illuminating to have somebody like Tuli really go through and enumerate the social and emotional atmosphere of all of those various eras.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Ilya Popenko

Jeffrey Lewis Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / YouTube / Bandcamp

Blang Records Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / YouTube / Bandcamp

Don Giovanni Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / YouTube / Bandcamp