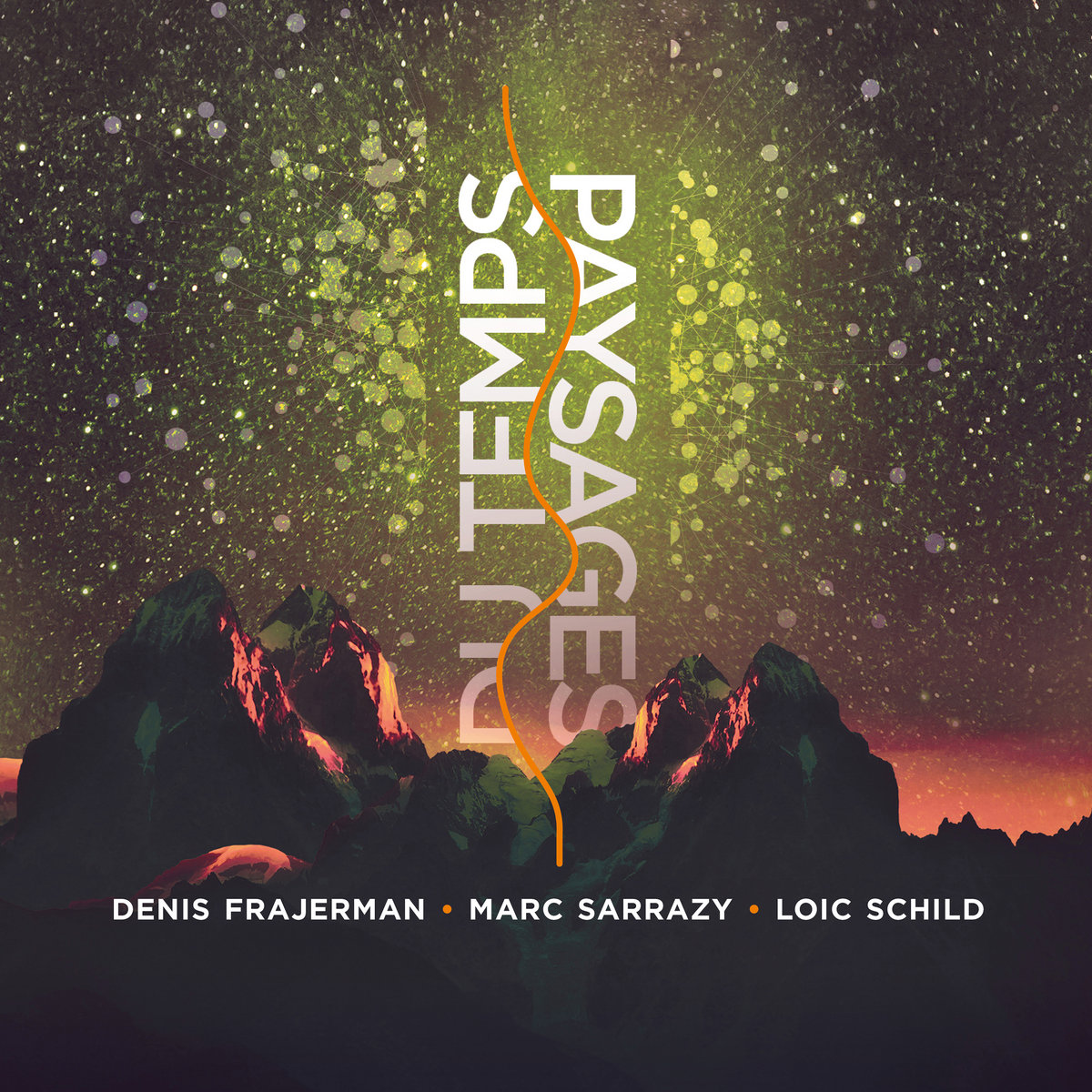

The Lost Psychedelic Soul of Jeannie Piersol: High Moon Unearths ‘The Nest’

High Moon’s latest release, ‘The Nest,’ is a long-overdue excavation of one of San Francisco’s most elusive voices, Jeannie Piersol.

A singer who drifted through the city’s psychedelic heyday like a half-remembered dream, Piersol ran in the same circles as Grace and Darby Slick, duetting with Grace in an early version of The Great Society before stepping out with her own band, The Yellow Brick Road. But it was a fateful trip to Chicago with Darby that sealed her place in underground rock history.

Signed to Chess Records’ hip subsidiary, Cadet Concept, Piersol cut a string of records that blended San Francisco’s free-flowing acid rock with the deep-pocketed groove of Chicago’s finest session players. The results were fuzzed-out, Indian-tinged, and dripping with soul, the kind of magic that should have made her a star. Instead, her two singles vanished into the ether, only to be rediscovered by those who dig beyond the obvious.

Now ‘The Nest’ finally gives Piersol’s recordings the spotlight they deserve, pairing them with unreleased tracks and live cuts that embody the spirit of the 60s. For the full story, check out our interview with Jeannie and producer Alec Palao.

“There were musicians everywhere—it was wonderful.”

It’s such a pleasure to have you here! It must feel incredibly rewarding to see so much of your material brought together in this beautiful anthology by High Moon Records. How did the project come about? What sparked the idea to compile all these tracks?

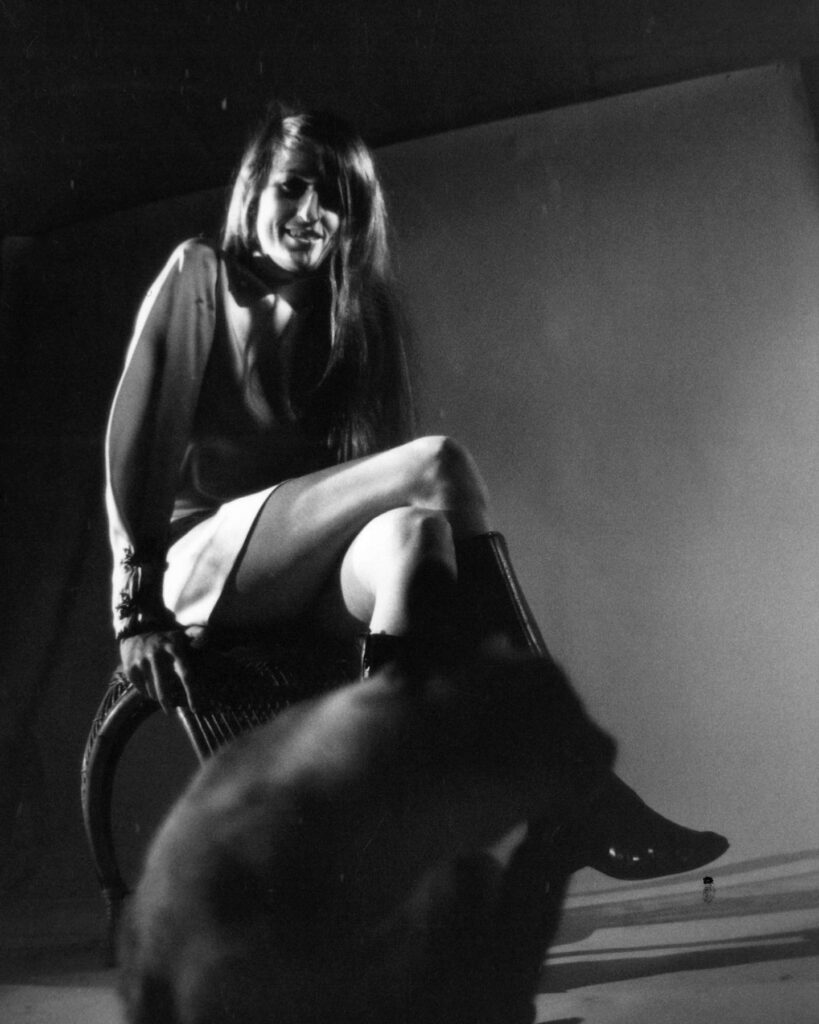

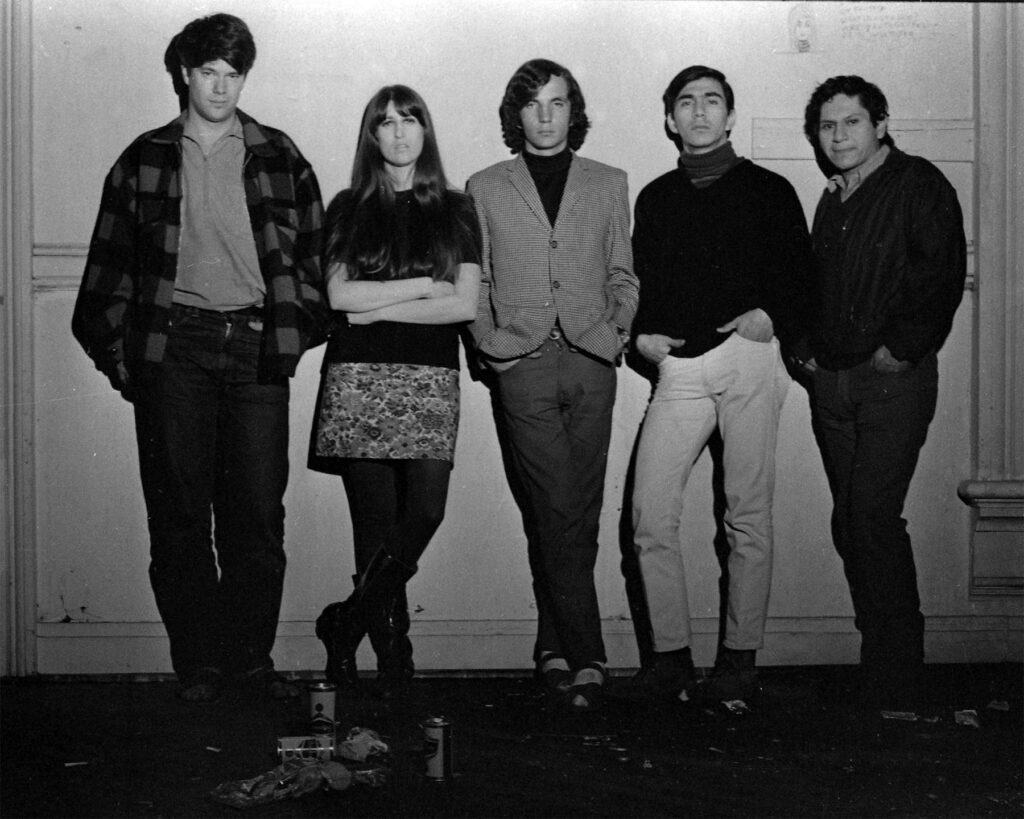

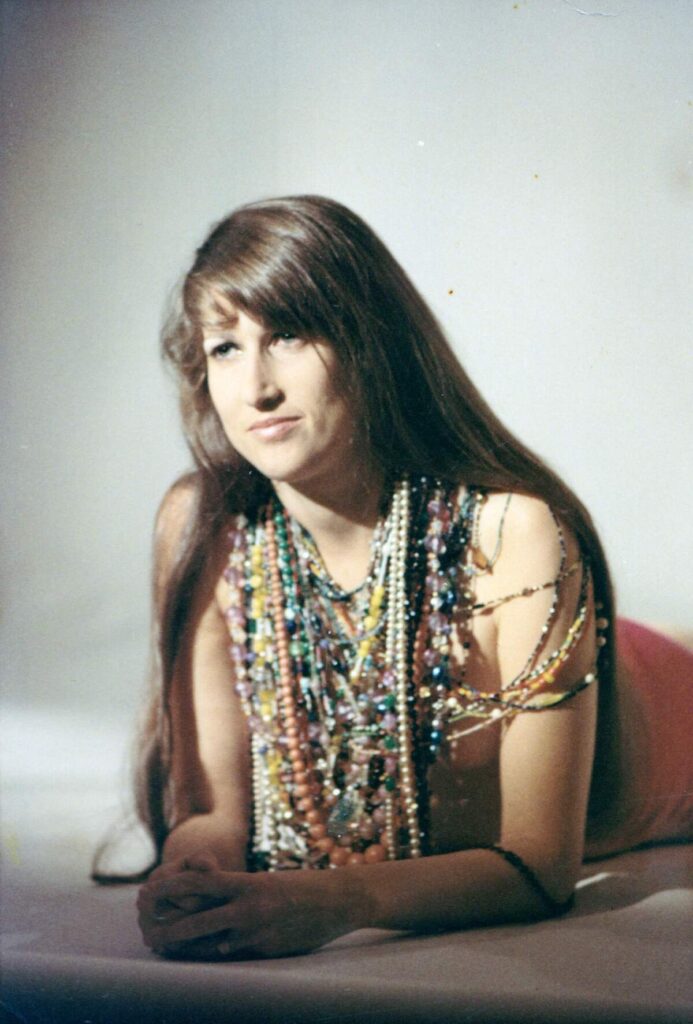

Jeannie Piersol: The project was driven by Alec Palao, who knew my music from the two singles I made and found most of the rest of the material thanks to his friendship with Sunny Anderson, daughter of our old friend Ray Anderson, who managed the Matrix and ran the Holy See light show. Ray had kept some of the unreleased stuff, as well as photos, and also the film for ‘Gladys.’ Alec found the Hair and Yellow Brick Road recordings and added those to create the project.

You came up in the same Marin County scene that nurtured legendary bands like Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead, and Big Brother. What do you remember most about the energy in the Bay Area music scene during the mid-1960s?

I remember it was wonderful. You’d go to the movies, and you’d see a band that you liked—they’d be going to the movies too. There were musicians everywhere—it was wonderful.

I would love it if you could discuss your early days. Where did you grow up, and how did you first get involved in music growing up?

I always loved music. My brother loved R&B music, and we would listen to all the black music stations, and that’s all the music I heard for a while.

And then, we used to sing in the car all the time. Jerry and Bill went to San Francisco State together. We’d go along and sing in the background—we did the background music. There was literally music in the air everywhere.

I imagine, in the early days, coffeehouses were the heart of the folk and blues scene. Were you part of that world as it was starting to take shape?

Coffeehouses? No.

You were close friends with Grace Slick and her brother-in-law Darby Slick, and you even duetted with Grace in early formations of The Great Society. What was it like working with Grace and the band?

She was really, really accomplished as a musician. She went to private schools in Palo Alto—she knew how to play lots of instruments. I was really just listening to the radio, but I didn’t have any training. Working with Grace and the band was fun, but there were a lot of drugs and alcohol at all the practices, and the rides home were scary. That made me quit the band. But I liked making music with them—we would cover great songs that were already popular, like ‘Sally Go ‘Round the Roses.’

I’d love to hear if there are any standout moments from that time. What were some of the venues where you played with The Great Society?

We played the Fillmore and the Avalon—the Avalon was fun. It was more relaxed. Van Morrison came in one night, turned his back to all of us, and said, “I won’t go on until I get my money.” Chet paid him, and he went onstage. He played the whole set and never looked at us.

Janis Joplin came in one night too and played—she was an amazing person. Every part of her dangled—feathers, beads. She was a force. She was just so fun.

How did you first connect with Grace, and what was she like in those early days? Do you still keep in touch?

Grace Wing, Jerry and Darby Slick, and my late husband Bill were all from Palo Alto. They grew up together. Grace was very talented—she liked to write. She was in our wedding party. She always had her own way of doing things. She named her daughter China “God” when she was first born, for example. When Jefferson Airplane took off, we were living pretty different lives. I haven’t been in touch with her for a while.

The track ‘Gladys’ holds such a unique place in your career, with its psychedelic soul flair and the backing vocals of Minnie Riperton. Can you walk us through the song’s creation, and what was it like working with Charles Stepney, Maurice White, and Minnie Riperton in the studio?

They were real musicians. When we came from California, they said, “Are you guys still “playing” at music?” The Bay Area didn’t really have studio musicians who were playing all the time for a living. Minnie Riperton and I became friends—she liked some hippie miniskirt I had, so I made her one and sent it to her in Chicago. You could tell her voice was something special.

Looking back on your career now, how do you feel about the work that’s collected in ‘The Nest’? Is there any particular track or moment from your time in music that you feel best encapsulates your voice and vision as an artist?

It’s so long ago that it’s pretty weird to hear the music now. But it’s fun too.

Since leaving the music industry, what have you been up to? Have you ever considered revisiting music or performance, or has your focus shifted to other aspects of life?

I left the music industry in the early 70s, at which point I was raising children. I recorded some songs for Sesame Street, but I didn’t feel like pursuing a music career after starting a family, which has been my focus ever since.

Alec, your work in resurrecting lost gems like Jeannie Piersol’s recordings feels almost archaeological. You’re dusting off these artifacts from the vaults of time. How do you walk that fine line between restoring these pieces while leaving their messy imperfections intact, knowing that those very flaws hold the soul of the era?

Alec Palao: Easy – as a doctor would say, “first do no harm,” or in other words, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. But in the case of the Jeannie Piersol tapes, as with many others I have worked on, there are not a lot of options for improvement, so to speak – so I tend to leave them largely as I find them, with just some tweaks to remove unwanted or extraneous, i.e., non-musical noise. There’s a verisimilitude to these recordings that shines through, and I would only want it to stay that way.

‘The Nest’ anthology is a journey through fragmented pieces—a mosaic of demos, live cuts, and unreleased tracks that offer a window into the Bay Area’s rock ‘n’ roll underworld. What story did you feel compelled to tell through this chaos, and were there any revelations along the way that left you rethinking the ’60s scene in a way you didn’t expect?

Over the decades, I’ve documented many Bay Area stories similar to Jeannie’s, and most have an individualistic aspect that makes them worth telling. In her case, there was an obvious potential for her to have moved further in her career, had she wished to. But we have to remember there was an almost suffocating amount of musical activity in San Francisco by the end of the decade, and it is no surprise many worthy artists, such as Jeannie, got lost in the shuffle. I do feel that the juxtaposition of her, and Darby Slick’s, direction with the players at Chess makes for a unique moment in SF-based rock.

You’re working with a mix of titans—Minnie Riperton, Maurice White, Charles Stepney—but also the more elusive voices that were lost in the shuffle. What did you learn about the undercurrents of that era, the invisible forces at play between the well-known figures and the ones who never got their due? And how did this shape your approach to the project as an archivist?

That juxtaposition I just mentioned, of Eastern-influenced, spatial and spiritual San Francisco rock with the heavy-duty jazz and R&B bona fides of the players at Chess, was rare in pop or rock up until that moment. Blues was at the core of many SF bands, but not too many had made an effective translation to performing and writing soul music. The Chess recordings have a wonderfully hip aura to them, and while completely ear-catching, they are not particularly easy to pigeonhole. Jeannie’s depiction of herself and Darby as wide-eyed hippies rubbing up against the seasoned Chess session crew is an odd and fascinating scenario, but the resultant recordings speak for themselves.

We’re living in an era where archival releases often get sterilized into some pristine, over-polished shell of their former selves. What motivated your decisions on ‘The Nest’ to keep things feeling a bit more raw? Were there certain cracks or rough edges you intentionally left intact to preserve the authenticity of Jeannie’s voice?

The simple answer is, they sound better that way. I was very familiar with Jeannie’s two singles, not to mention the fantastic production values of Chess in the mid to late 1960s, so I endeavored to keep everything in that same ballpark as much as possible. There is an inherent warmth to the sound of that era that is nigh impossible to recapture or enhance with modern techniques, so why even try?

Restoring decades-old tapes is one thing, but curating an anthology like ‘The Nest’ must’ve taken a toll on you in ways that go beyond the technical side.

The main work that was done was restoring the couple of tracks that necessarily had to be taken from disc, but otherwise, it was a fairly streamlined process – as you know, I have plenty of experience in grappling with ancient source material! But the important thing to remember about ‘The Nest’ LP is that this is pretty much the sum total of Jeannie’s recorded legacy, give or take a few more live tracks by the Yellow Brick Road. The fact that it all neatly dovetailed together is pretty remarkable.

After diving deep into Jeannie’s world, what’s something you’ve learned about her that’s as unexpected as it is fascinating?

What was unexpected to me was how nonchalant Jeannie was about stepping away from the music business. She obviously gave her all on those Chess recordings, and she extrapolated upon Darby’s direction very well indeed, especially on the Indian-flavored material. But she chose to give it up and do other things – as a musician and something of a music-mad “lifer” myself, I do find that slightly puzzling – but completely admirable.

If you had to pick one track from Jeannie’s vault that perfectly captures the spirit of the time, what would it be and why?

‘Your Sweet Inner Self’ – just fabulous on all counts – musically, arrangement and production-wise, and infused with a joyous message that just has to put a smile on your face as much as the sound should affect the rest of your being.

Klemen Breznikar

High Moon Records Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / YouTube / Bandcamp

This IS a marvellous cd, Alec Paulo has become the go to guy for excellent archival releases like this, particularly in the realms of psychedelic, garage and folk rock sounds of the 60s.

The mix of sounds on this release fit surprisingly well with raga like moments fitting in seamlessly with Soulful folky moments,it really does show the pot pourri of sounds from this marvellous age of music that was the later 60s.

The booklet has beautiful period photos and thorough liners telling the story of not just Jeannie Piersons musical career but also the musical environment in which was taking place at that time.Where both professional musicians and inexperienced musical participants worked together for the greater good of the music.

A marvellous musical archival document from a period that Will never be repeated.